A tourism surge meets tight control

Across China, social media feeds showcase snowy peaks, turquoise lakes, camel caravans on desert dunes, and neon lit night markets in Xinjiang. The region recorded roughly 300 million visits in 2024, according to regional figures, making it one of the most talked about destinations in the country. The majority of visitors are domestic travelers who report smooth highways, frequent flights, polished attraction sites, and a promised sense of safety. Travel agencies package itineraries that mix Silk Road history, scenic drives, and staged performances featuring dance and music that are branded as ethnic experiences.

- A tourism surge meets tight control

- How Xinjiang became a showcase destination

- What visitors see, and what they miss

- The rights record behind the postcard views

- Travel is easy for tourists, hard for many Uyghurs

- Business is booming, scrutiny is growing

- Shaping the narrative: summits, curated tours, and counter messages

- What travelers and companies should weigh

- The Essentials

The postcard view sits alongside a very different reality. Xinjiang is home to most of China’s more than eleven million Uyghurs, a mostly Muslim, Turkic speaking people. Since 2017, rights organizations and a 2022 assessment by the United Nations human rights office said authorities carried out mass detention, pervasive surveillance, and severe restrictions on religion and culture. That assessment concluded the violations could amount to crimes against humanity. Chinese officials reject these accusations, describing programs as legal measures that counter extremism and bring development, and they have tightly limited independent access to the region. Many Uyghurs living abroad still cannot reach family members back home.

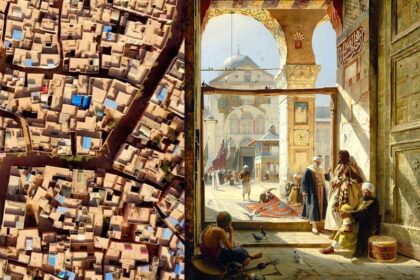

Even as security controls evolve, access for outsiders has been curated. Tourists typically interact with Han Chinese drivers and guides, and visits to religious sites happen under strict rules or not at all. Bazaars and historical districts that appear ancient are often recent reconstructions. Rights groups say large numbers of mosques and traditional neighborhoods were demolished over the past decade. As public messaging leans into a narrative of harmony and prosperity, the tourism boom raises a central question for visitors and businesses: what is on view, and what is out of sight.

How Xinjiang became a showcase destination

Xinjiang sits at the heart of China’s westward ambitions, both historic and modern. The ancient Silk Road passed through its desert oases and mountain passes. Today, it is a strategic link in the Belt and Road Initiative, with major investments in transport, energy, and logistics. New airports, expanded rail lines, and upgraded expressways have cut travel times across vast distances. Cities such as Urumqi, Kashgar, and Turpan promote four season tourism with winter skiing, spring flower festivals, and summer and autumn routes that connect canyon hikes, grassland meadows, and restored caravan towns.

Billions for roads and resorts

Public spending and private capital flowed into theme parks, resort hotels, visitor centers, and cultural parks that host choreographed shows. Tourism bureaus partner with influential travel bloggers to spread content on Chinese platforms. Scenic areas have added cable cars, shuttle fleets, and ticketing apps. The intent is simple: make Xinjiang feel reachable, safe, and visually spectacular for mass market travelers.

Sales pitch built on culture and safety

Tour programs sell local flavor through food, costumes, dance, and music. At the same time, messaging stresses order and stability. Security checkpoints that once interrupted drives have been reduced in some tourist corridors or made less visible to the casual visitor. The experience often avoids sensitive neighborhoods, mosques, and cemeteries unless they are part of curated stops. That creates a script that is heavy on scenery and spectacle and light on authentic interaction with Uyghur life.

What visitors see, and what they miss

Many travelers report that guides highlight safe areas and steer groups along set circuits. These include desert photo points near Dunhuang and Turpan, ancient city facades in Kashgar’s old town that were rebuilt or renovated, and lively night markets serving kebabs and naan. The result can feel theatrical. Performers dance in ornate clothing, while the audience flows past souvenir stands stocked with tambourines and embroidered hats. Outside these venues, it is harder to witness unscripted daily life or attend prayer at a functioning mosque.

Official tours for foreign delegations have been even more controlled. Experts and activists describe invited trips that showcase model villages, schools, factories, and approved cultural sites. Visitors are sometimes encouraged to post positive footage online. Critics refer to this as genocide tourism, arguing that it substitutes glossy showcases for independent observation and masks contemporary restrictions on religion, language, and movement. Independent journalists, researchers, and exiled community members say they face visa hurdles and heavy monitoring that make free reporting or family visits extremely difficult.

Rights groups have documented large scale demolition or alteration of mosques, cemeteries, and neighborhoods described as dilapidated or unsafe by authorities. Traditional architecture has given way to uniform apartment blocks in some areas, and cultural displays are recast as performances for consumption, not expressions of community life. The presentation is polished. The texture of ordinary Uyghur life is harder to find.

The rights record behind the postcard views

According to the United Nations human rights office, large scale abuses began to accelerate in 2017, when authorities initiated sweeping policies targeting Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities. Researchers and survivor accounts describe mass detention in political reeducation centers and formal prisons, bans or tight limits on religious practice, pressure to abandon Islamic names and customs, and campaigns to reshape identity under the banner of anti extremism. Authorities refer to closed facilities as vocational training centers and say they were necessary to stem violence. The UN assessment and multiple investigations found credible reports of torture, sexual violence, and family separations.

Coercive labor programs have also drawn scrutiny. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), a powerful paramilitary and economic entity, runs farms, factories, and township level administration. It has been sanctioned by several governments for human rights abuses. Investigations by labor agencies and rights groups have linked cotton, tomato products, polysilicon used in solar panels, and other goods to coercive labor schemes in Xinjiang and transfers of Uyghur workers to factories elsewhere in China. In response, the United States enacted the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in 2021, which presumes goods made in Xinjiang, or by listed entities, are produced with forced labor unless proven otherwise. Companies trading globally face serious compliance risks if they cannot document clean supply chains.

Security measures still shape daily life. Research describes a dense surveillance network that includes frequent ID checks, biometric data collection, and smartphone monitoring. While some practices are less visible than at the height of the campaign, surveillance and political indoctrination programs have not disappeared. Families report loved ones in prison after unfair trials, and many abroad say they cannot call home without endangering relatives. These accounts stand in sharp contrast to the imagery of carefree travel and open cultural exchange that dominates tourism marketing.

Travel is easy for tourists, hard for many Uyghurs

Reports from human rights researchers indicate that movement controls target Uyghurs both inside China and in the diaspora. Passports were widely confiscated during the height of the Strike Hard campaign, and while some people have regained documents, approvals remain arbitrary and subject to close scrutiny. Accounts collected by researchers describe rules that permit only one family member to travel at a time, with spouses and children effectively used as leverage to ensure that the traveler avoids activism, media contact, or critical speech. Some Uyghurs who live abroad face long waits for visas to visit relatives, and many are steered toward official tours that require Mandarin language ability and participation in staged activities.

Those returning from overseas trips often encounter questioning, device checks, and renewed confiscation of passports. Travelers who share images or statements that contradict official narratives can face consequences on return. These practices help explain why so many Uyghurs in exile say they have lost contact with parents, siblings, and friends. A region that now welcomes waves of tourists can remain largely closed to members of the community whose culture those tourists are encouraged to sample.

Business is booming, scrutiny is growing

The hotel sector shows how the tourism push intersects with concerns about rights and accountability. A recent study by a Uyghur advocacy group identified almost 200 international branded hotels operating, under construction, or planned in Xinjiang. It found dozens already open and many more underway, including projects by major global chains. Some of these hotels operate in areas administered by the XPCC, which is under sanctions in the United States and other jurisdictions. Investigators also tied specific locations to policies that transfer labor and to construction on sites where religious buildings once stood.

Corporate leaders face a choice between access to a growing travel market and reputational, legal, and ethical risk. Automakers and apparel companies have already struggled with questions about labor sourcing, verification, and audits in Xinjiang. Under the UFLPA and similar measures, customs authorities can detain shipments that appear linked to coercive labor. Investors and executives must weigh profit forecasts against the reality that independent verification in the region is constrained, and that participation can be used in public messaging to project normalcy.

Peter Irwin, who leads advocacy at the Uyghur Human Rights Project, has warned that prominent hotel brands are now part of Beijing’s effort to present Xinjiang as a normal holiday spot. Irwin argues that the presence of these brands helps launder the region’s image while the core problems remain.

International hotel expansion supports the Chinese government’s strategy to normalize perceptions of the Uyghur region.

Pressure campaigns have delivered some results. One global carmaker sold its Xinjiang factory after years of criticism. Advocacy groups are now urging hotel chains to freeze expansion, review operations, and provide public transparency about land use, supply chains, and hiring, including recruitment programs that may channel transferred labor.

Shaping the narrative: summits, curated tours, and counter messages

Beijing has invested in opinion shaping at home and abroad to counter reports of abuse. The region recently hosted a world media conference in Urumqi with hundreds of participants. State outlets highlighted modernity and openness and gave the floor to international attendees who praised what they saw. Critics viewed the choice of venue as deliberate signal management to present technology, development, and hospitality rather than detention, surveillance, and assimilation policies.

Adrian Zenz, director of China studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, said the event was part of an effort to rebalance the global conversation away from rights concerns and toward economic growth and stability. He has studied policy documents and procurement records that track the growth of the detention and surveillance system in Xinjiang.

This event appears to be designed to normalize the situation in Xinjiang, making Xinjiang a location for discussing modern technology and developments.

Uyghur activists were sharply critical of the involvement of established media brands and public figures at the Urumqi gathering.

It is disheartening that these esteemed media organizations have chosen to partake in a Chinese propaganda event. Their presence provides unwarranted legitimacy to China’s colonial and genocidal policies in East Turkistan.

Beyond conferences, a steady flow of invited delegations and study tours has created a parallel information channel. A recent controversy over an academic publishing delegation underscored how curated itineraries and selective filming can produce content that later appears in state media as endorsement. Analysts compare these trips to Potemkin style visits in the twentieth century, where foreign guests were guided through model sites to create an image of normal life. Fact checking is complicated by limits on travel and interviews, which leave much of the region off limits to independent reporting.

What travelers and companies should weigh

Travelers who want to understand the region face practical limits. Tourists have little control over access to religious sites, prisons, or ordinary homes. Guides often discourage contact with locals beyond transactional interactions in markets or restaurants, and photographing police or checkpoints can lead to questioning. Visitors who still choose to go can make informed decisions about what to photograph and post, avoid praising staged interactions as proof of harmony, and learn from the work of researchers and community voices outside the region.

For companies, the compliance challenge is acute. Supply chains that touch Xinjiang carry a presumption of forced labor under U.S. law, and auditors cannot freely investigate worksites. Hotels and tour operators must assess land histories, construction records, and staffing pipelines for ties to sanctioned entities or government labor transfers. Boards and investors should expect public disclosure and regular risk updates, because silence will be read as indifference or worse. In sectors like solar, cotton, tomatoes, and aluminum, tracing inputs back to source is essential for access to Western markets.

Governments that host large numbers of tourists and investors have options. Officials can press for independent access for UN experts and journalists, expand visa support for Uyghur families seeking reunions, and enforce targeted sanctions against agencies and executives credibly tied to abuses. Legislatures can strengthen import controls and fund enforcement so that the burden does not fall only on a few high profile cases. These steps, combined with vigilant civil society work, can create incentives for change even when direct investigation inside Xinjiang is constrained.

The Essentials

- Xinjiang recorded around 300 million tourist visits in 2024, mostly from domestic travelers, after heavy investment in transport, attractions, and marketing.

- Tourism packages emphasize scenery and staged ethnic performances while limiting unscripted contact with Uyghur communities and religious life.

- A 2022 UN human rights assessment found that violations in Xinjiang could amount to crimes against humanity; China denies abuses and restricts independent access.

- Research details mass detention since 2017, family separations, pervasive surveillance, and coercive labor programs tied to sectors such as cotton, tomatoes, and polysilicon.

- Uyghurs face heavy travel restrictions, with accounts of passport confiscations, close monitoring, and rules that limit overseas trips to one family member at a time.

- Nearly 200 international branded hotels operate or are planned in Xinjiang, including projects in areas run by the sanctioned XPCC, raising legal and ethical risks.

- Advocates urge global hotel chains and other firms to freeze expansion, review land and labor ties, and disclose risks under laws like the U.S. UFLPA.

- China hosted a high profile media summit in Urumqi to promote an image of modernity and safety; activists and experts say such events normalize ongoing repression.

- Travelers, businesses, and governments can make informed choices by avoiding propaganda framing, demanding transparency, and supporting independent scrutiny.