A silent threat in daily meals

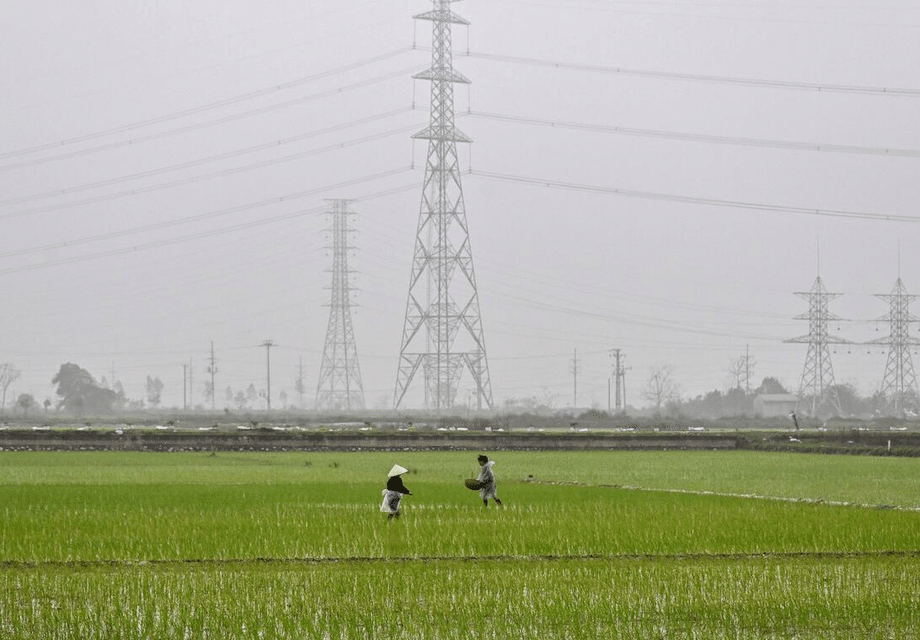

Counterfeit labels, banned chemicals, and food with unclear origin are still finding their way into school canteens, street markets, and even modern supermarkets in Vietnam. Specialists at a recent workshop in Hanoi warned that weaknesses in production, distribution, and oversight allow risky products to slip through. The result is a public health problem that erodes consumer trust and penalizes honest farmers and businesses.

- A silent threat in daily meals

- Why VietGAP adoption lags

- From farm chemicals to the dinner table

- Weak links in distribution and traceability

- New institutions and digital tools

- Export pressure is raising the bar

- When food safety fails

- What will build trust at home

- Practical steps for shoppers and vendors

- What to Know

Vietnam’s agriculture is large and diverse, with about 10 million farming households cultivating roughly 1.15 million hectares of vegetables and 1.3 million hectares of fruit. Yet only a small share meets recognized safety standards. VietGAP, introduced in 2008 as a national benchmark for safe production, still covers a small portion of the country’s fields. A 2024 survey indicates that less than 1 percent of vegetable acreage has VietGAP certification. For fruit, about 76,000 hectares are certified, and for tea the figure is around 5,200 hectares. Counting other standards alongside VietGAP, the total certified area is about 440,000 hectares, modest compared with nationwide demand and daily consumption.

The last link between farm and table is also vulnerable. Vietnam has more than 8,200 markets, nearly 300 trade centers, and about 1,300 supermarkets. Big suppliers to modern retailers tend to comply with safety rules and have better documentation. In traditional markets, small traders often rely on verbal assurances. Oversight is even weaker at scattered stalls and small shops, where authorities face a challenge in verifying origin and storage conditions.

Why VietGAP adoption lags

Industry groups argue that VietGAP should be a minimum requirement for produce. Yet only an estimated 5 to 6 percent of vegetables meet that standard. When such a basic benchmark is not widely met, the domestic market becomes difficult to regulate, and consumers bear the risk. Vegetables, which most people eat daily, have some of the lowest compliance rates, while many fruits that do meet higher standards are grown for export rather than for local shoppers.

Farmers cite several barriers. Certification requires records, audits, and training. Smallholders, who dominate production, struggle to shoulder those costs without guaranteed price premiums. Testing and inspection capacity can be patchy in rural areas. Retail demand for verified produce is also uneven, so many growers do not see a reliable return on investment. Exporters often pursue certification because foreign buyers insist on it, which explains why fruit zones destined for overseas markets have better compliance than vegetables sold domestically.

Vietnam has reworked its food safety system since the 2010 Food Safety Law. The law and subsequent reforms brought modern administrative principles, clearer labeling rules, and more regular controls. The National Food Control System spans the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Coordination has improved, but overlapping responsibilities and limited resources make enforcement hard, especially in the informal sector where many small producers and vendors operate. Risk assessment remains a work in progress, and laboratory capacity is uneven across regions.

From farm chemicals to the dinner table

Residues from pesticides and veterinary drugs pose a persistent risk when farmers do not respect rules on what to use and when to harvest. The most common problem is ignoring the pre harvest interval, the required time between the last application and harvest. When crops are pulled early, residues may remain above acceptable levels. The health burden often does not show up immediately, which makes these risks harder to detect. Children, older adults, and pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to long term exposure.

What are residue limits and pre harvest intervals

Maximum Residue Levels, or MRLs, are the highest concentration of a chemical legally allowed in or on food. Regulators set these limits after risk assessments that consider how much of a food people typically eat and how the chemical behaves in the body. An MRL is not a toxic threshold. It is a legal ceiling designed to keep daily exposures safely below health reference values. Pre harvest intervals give time for residues to degrade to acceptable levels before the product reaches consumers.

In Vietnam, most farmers try to handle pests responsibly, but gaps remain. Some may use products that are not registered for certain crops. Others rely on advice that is out of date or do not maintain records. When markets reward speed and appearance, the temptation to harvest early can override safety rules. That is why enforcement, practical training, and reliable testing matter.

Weak links in distribution and traceability

Safety does not end at the farm. Many risks arise in transport, storage, and retail. Without chilled trucks or clean containers, meat and seafood can spoil before reaching the market. Stalls that lack stainless steel counters, potable water, or basic protective gear can contaminate otherwise safe products. Even where products and transport meet standards, poor handling at the stall can undo that effort.

Regulatory procedures have also shifted. In 2018, Vietnam replaced a heavy pre inspection approach with a post inspection model. Under the newer rules, a large share of shipments move without immediate checks, and companies self announce compliance. Random inspections still occur and can target up to a small fraction of imports. The change reduced paperwork and cost, but it places more responsibility on businesses and regulators to detect problems after distribution starts. That works best when traceability is robust and penalties deter cheating.

Decentralized enforcement means provincial authorities often carry the burden of inspecting markets and shops. When rules change, local agencies need time and resources to implement them. Traceability for small vendors remains limited, which complicates product recalls and investigations. To fix this, the Ministry of Industry and Trade is drafting a circular that would introduce a digital passport for each product by May 2026. If well designed, a simple code that links a product to its origin, inputs, test results, and distribution path can make investigations faster and fraud harder.

New institutions and digital tools

Vietnam is building a more scientific approach to food safety. The Vietnam Centre for Food Safety Risk Assessment, managed under the National Institute for Food Control, will prioritize early risk identification and data collection. Its mandate includes running risk studies in local supply chains, guiding standards, and developing a national database. The goal is to provide scientific evidence that supports legal action against violations and gives regulators a clear picture of where the biggest hazards lie.

Authorities are also developing a digital food safety management system in partnership with South Korea. A core feature is real time reporting of food poisoning outbreaks so officials can respond quickly to prevent wider harm. Over time, a shared data platform across ministries can improve coordination, highlight recurring problems, and help target inspections where they matter most.

How a risk based system changes the job

A risk based model shifts attention from checking everything to checking the right things. Inspectors prioritize products, regions, or practices that data show are high risk. That approach saves resources and reduces unnecessary delays for low risk goods. It depends on credible data and strong traceability, because decisions are only as good as the information behind them.

Export pressure is raising the bar

External markets are pushing change inside Vietnam. The European Union requires compliance with Maximum Residue Levels for pesticides, bans specific chemicals, and demands phytosanitary certificates for most fresh produce. Nordic retailers often apply standards that exceed the EU baseline. Vietnamese exporters must meet these demands to keep access to valuable markets, which means precise control over inputs and strong documentation.

Regulators and industry are paying closer attention to warning systems such as the EU Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed. Vietnam received fewer warnings in early 2025 than in the prior year, yet the number remains a concern. Agencies have urged producers to tighten controls on pesticides and antibiotics, test more before export, and strengthen traceability and quality systems such as HACCP, GlobalGAP, ASC, and BRC. Many small and medium enterprises are still learning new rules on categories such as novel foods and mixed products, which adds to compliance challenges.

Other measures are on the horizon. The EU’s deforestation regulation will require proof that products such as coffee, rubber, and wood do not come from land linked to deforestation. The EU is also preparing limits on inorganic arsenic in fish and crustaceans. From late 2026, the EU will ban antimicrobials used in human medicine or as growth stimulants in animal products. In the United States, the Marine Mammal Protection Act will take full effect on January 1, 2026. Exporters will need bycatch protections comparable to those in the US. These rules press Vietnam to upgrade monitoring, traceability, and sustainability throughout supply chains.

Compliance is not just a technical issue. When certification procedures change, shipments can stall. Since July, one rule requires that government authorities, not private bodies, issue certain food safety certificates for exports to the EU. Some provinces have needed time to establish the correct processes. Fruit and vegetable shipments have faced delays and extra storage costs, which hurts both growers and importers. Industry representatives, including leaders from the dragon fruit sector in Binh Thuan, have urged a rapid fix so produce is not held at ports.

There are signs of targeted solutions. For example, Vietnam has issued detailed food safety procedures for fresh durian exports, setting requirements from cultivation and harvesting through packing and shipping. Plantation areas are inspected and assigned identification codes, which strengthens traceability and provides a model that other crops can follow.

When food safety fails

Incidents still occur with serious consequences. In late 2024, a banh mi shop in Vung Tau was linked to a large outbreak of foodborne illness. More than 340 people fell ill and one person died. Investigators found contamination by Salmonella and E. coli, likely coming from pork products and raw vegetables. Authorities fined the owner and suspended operations. The case echoed earlier mass incidents, including events that sickened hundreds of people in different provinces.

These outbreaks share common patterns. Contamination can spread when raw meat juices touch vegetables or cooked foods. If refrigerators are overloaded or not cold enough, bacteria multiply quickly. When staff are rushed and tools are reused without proper cleaning, any pathogen on one ingredient can reach many customers. The science is straightforward. Salmonella and E. coli can be killed by thorough cooking. Clean water, separate cutting boards, and safe storage temperatures are basic protections. The WHO Five Keys to Safer Food, keep clean, separate raw and cooked foods, cook thoroughly, keep food at safe temperatures, and use safe water and raw materials, remain relevant for households, shops, and school kitchens.

What will build trust at home

Solutions are emerging. The proposed digital passport for products, planned for 2026, can connect what consumers see on a label with verified data on origin, inputs, and test results. If every shipment carries a scannable code, vendors can prove compliance on the spot and regulators can trace a problem back to the source within hours. This transparency also gives buyers confidence to pay for quality.

Input control must tighten. Farmers need clear guidance on which chemicals are allowed and how to apply them, and retailers should reject supplies that do not meet pre harvest intervals. Crackdowns on illegal pesticides and unscrupulous distributors help level the field for honest producers. Training delivered through cooperatives and community groups can raise skills quickly, especially in places where smallholders need practical advice on record keeping, compost use, integrated pest management, and clean water.

Infrastructure upgrades at markets matter. Simple investments in potable water points, stainless steel surfaces, handwashing stations, and reliable cold storage reduce contamination risks. Better transport, including insulated crates and chilled trucks, keeps fish and meat safe in Vietnam’s hot climate. Independent laboratories and mobile test units can support faster checks. E commerce platforms and supermarket chains can require traceability information from their suppliers, which nudges the entire ecosystem toward better practices.

Coordination is also key. Agencies that share responsibility, including the health, agriculture, and industry ministries, need connected databases, common definitions, and timely data sharing. The new risk assessment center can act as a hub for evidence and early warnings. Officials and producers agree that raising consumer awareness is crucial. When buyers demand safer products and reward documented quality, the market begins to reinforce good behavior.

Practical steps for shoppers and vendors

Food safety is a shared responsibility. Consumers, vendors, schools, and regulators each have a role in reducing risk and improving trust. Small changes, when widely adopted, make a big difference.

For consumers

- Buy from vendors who can explain origin and show basic documentation such as VietGAP, GlobalGAP, or store-specific quality stamps.

- Look for clean stalls, cold storage for meat and seafood, and separate areas for raw and cooked foods.

- Wash vegetables under running water, peel when possible, and air dry before storage.

- Keep raw and cooked foods separate at home, use different cutting boards, and clean tools between tasks.

- Cook meat, seafood, and eggs thoroughly. Refrigerate leftovers within two hours.

- Use safe water for washing and cooking. When in doubt, boil or use bottled water.

- Scan product codes when available to check origin and dates. Avoid items with unclear labels or no date information.

For small vendors and school kitchens

- Maintain temperature logs for refrigerators and hot holding. Calibrate thermometers regularly.

- Store raw meat below ready to eat foods. Use color coded tools to prevent cross contamination.

- Adopt simple checklists based on HACCP principles to control key hazards in prep, cooking, and storage.

- Use potable water and approved cleaning agents. Train staff on handwashing and surface sanitation.

- Track batch origins and delivery dates. Keep basic digital records on a phone or tablet for quick access.

- Work with local authorities to understand new traceability and certification requirements. Ask for training when rules change.

- Reject supplies that arrive warm, damaged, or without clear documentation.

What to Know

- Vietnam’s food safety system has improved since 2010, yet enforcement remains difficult in informal markets and small scale production.

- VietGAP coverage is small, with less than 1 percent of vegetable acreage certified and modest adoption across other crops.

- Pesticide residues and weak compliance with pre harvest intervals continue to pose health risks.

- Distribution and retail are weak links, with limited traceability and uneven market infrastructure.

- A digital passport for products is being drafted for 2026 to improve traceability and accountability.

- A new national risk assessment center will prioritize early hazard detection and build a shared data system by 2030.

- Export rules from the EU and US are pushing higher standards on residues, traceability, sustainability, and animal welfare.

- Recent outbreaks tied to ready to eat foods show the cost of poor hygiene in handling and storage.

- Better input control, practical training, market upgrades, and connected data can lift safety across the chain.

- Consumers and vendors can apply simple steps, including WHO’s Five Keys, to reduce everyday foodborne risks.