Autumn brings a surge in mosquitoes

Summer heat starts to fade across Japan, yet the whine of mosquitoes often grows louder. Many residents expect relief after August, then find that bites become more frequent in September and October. Experts point to a simple driver. As temperatures ease from midsummer highs, mosquito activity climbs. According to industry observations shared by Tomoko Kahara of Dainihon Jochugiku, fall has become the season with the most mosquitoes in recent years. That shift reflects warmer autumn weather and a biological pattern that favors cooler but still mild conditions.

Mosquitoes do not stop breeding when the mercury climbs. They often rest in shaded shrubs, under decks, or inside sheds during the hottest hours. They continue to lay eggs in tiny pools of water. When daytime temperatures move back toward a comfortable range, they return to active flight and feeding. The sweet spot for activity is around 27 degrees Celsius. Above 30 degrees, they hide. When the heat breaks, they fly again.

Female mosquitoes need blood to produce eggs, and an adult mosquito lives for about a month. In early autumn, cooler mornings and evenings allow more movement during the day, so females search for hosts more frequently. Many people experience intense itching. That itch is an allergic response to proteins in mosquito saliva. While the bite itself is quick, the redness and swelling can last for days, especially if scratched.

How temperature shapes activity

Temperature sets the pace for all parts of the mosquito life cycle. Around 27 degrees Celsius, flight, feeding, and egg development all proceed efficiently. Above 30 degrees, activity slackens as mosquitoes conserve energy in shade and vegetation. When temperatures fall below about 15 degrees Celsius, flight and feeding drop sharply, and mosquitoes begin to disappear from porches and parks. Until then, they can be tenacious. Rain after a warm spell produces new breeding sites, and a single week of mild weather can keep a local population going.

The species behind the bites

In Japan, two types of mosquitoes drive most human bites. The Asian tiger mosquito and the common house mosquito thrive in cities and suburbs. They exploit small containers, gutters, and planters, and they move between shade and human living spaces with ease. Both favor water that collects in places people overlook, which is why prevention starts at the household level.

Asian tiger mosquito

Aedes albopictus, often called the Asian tiger mosquito, is a container breeder that lays eggs on the sides of small water vessels, from bottle caps to planter saucers. It is active during the day and will also bite at dawn and dusk. The species has a bold black and white pattern, a quick flight, and a very persistent bite. Public health literature identifies it as a capable vector of viruses such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika in regions where those viruses circulate. It adapts to different climates and can survive cooler winters by producing eggs that enter a resting state. That adaptability, combined with urban container breeding, makes it a stubborn nuisance in autumn.

Common house mosquito

House mosquitoes in the Culex group tend to bite in the evening and at night. They often live near homes and can enter through unscreened windows or doors. Many rest indoors in quiet corners. They prefer stagnant or organically rich water, such as clogged gutters, storm drains, or neglected water features. While they are less aggressive than Asian tiger mosquitoes in daylight, they extend biting risk into the night, especially in mild autumn weather when windows remain open.

Together, day biters and night biters keep the pressure on households throughout early to mid autumn. Where shade, water, and people overlap, bites increase. That is why removing standing water and using repellents remain the two pillars of prevention every fall.

Why some people get bitten more often

Mosquitoes find people through a combination of cues. They sense carbon dioxide from exhaled breath, warm skin, and volatile chemicals released in sweat. A person who has just jogged, carried groceries up stairs, or enjoyed a hot meal outdoors is more attractive to a nearby mosquito. The plume of carbon dioxide and body heat creates an easy target.

Sweat alters skin chemistry in a way mosquitoes can detect. Lactic acid and other compounds produced during exercise can draw them in. The natural bacteria that live on our skin also shape scent. Some skin microbiomes produce odors that appeal to mosquitoes more than others. While you cannot change your skin microbes overnight, you can lower risk by cooling down and rinsing sweat before heading outside for a long period.

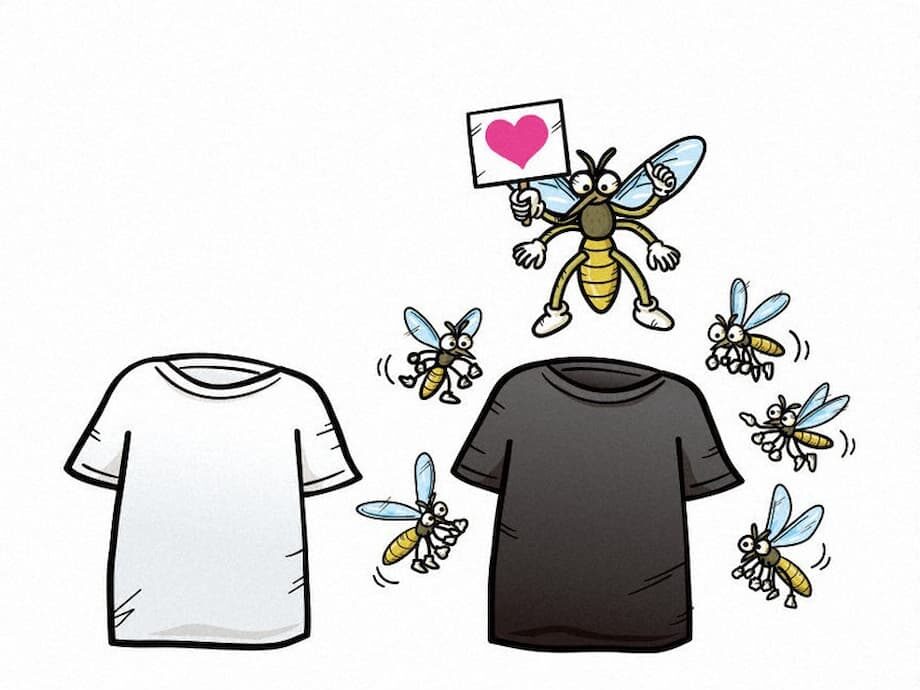

Dark clothing stands out to the mosquito eye. Black and deep navy appear as strong contrasts in low light. Choosing lighter colors reduces visibility. Alcohol can also raise risk by changing skin temperature and blood flow. People often report more bites after an evening drink on a terrace or at a festival. Consider seating with a fan, which disrupts flight and disperses carbon dioxide.

Stop mosquitoes at home by removing water

Effective control starts with the simplest measure. Do not let water sit. Many urban mosquitoes lay eggs in tiny amounts of water that are easy to miss. A single planter saucer can produce dozens of adults in a week of warm weather. Regular checks every few days will break the cycle.

- Empty and scrub plant saucers, buckets, flowerpots, bottle caps, and any small container that holds rainwater.

- Turn over bins, wheelbarrows, and storage containers when not in use.

- Clear leaves from gutters so they drain freely after rain.

- Check yard drains, stairwell wells, and low spots that collect puddles. Improve drainage where possible.

- Dispose of old tires. They are a classic breeding site.

- Change water in vases, pet bowls, and birdbaths frequently. Aim for every two to three days during warm spells.

- Cover rain barrels with tight mesh to block egg laying. Seal gaps where mosquitoes could enter.

- Use larvicide products only as directed on the label when local guidance permits. Follow safety instructions.

- Repair window and door screens. Close gaps where insects can slip indoors.

- Use a fan on balconies and patios. Airflow reduces landings.

Neighborhood effort multiplies results. If several homes on a block remove standing water at the same time, adult numbers fall before they build to an autumn peak. Remind building managers to check rooftop drains and light well sumps. A little attention in these hidden spots suppresses breeding for many apartments at once.

Repellents, clothing, and coils: what works

Public health agencies advise using an EPA registered insect repellent (EPA) when mosquitoes are active. Products with DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus or its synthetic form known as PMD, and 2 undecanone protect well when applied as directed. These ingredients have been tested for safety and effectiveness. Choose a product you are comfortable using and keep it in a spot you can grab on your way out the door.

Apply repellent to exposed skin or clothing according to the label. Do not spray under clothing. Use just enough to cover lightly. Reapply as instructed, which may vary by ingredient and concentration. Wash hands after applying, especially before eating or touching eyes. For children, an adult should apply repellent to their hands first, then rub it onto the child, avoiding hands and eyes.

Pregnant and breastfeeding people can use EPA registered repellents. For small children, choose age appropriate products and follow the label closely. Do not use oil of lemon eucalyptus or PMD on children under 3 years. If you have sensitive skin or a specific health concern, ask a healthcare provider for guidance.

Clothing and gear can add another layer of protection. Treat items with permethrin products designed for fabrics, or buy pretreated items. Do not apply permethrin directly to skin. Treated clothing keeps its effect through multiple washes, depending on the product. Long sleeves, long pants, socks, and closed shoes reduce exposed skin. Tuck pants into socks if you will be in tall grass or near dense vegetation.

Mosquito coils and electric vaporizers are widely used in Japan. Coils contain pyrethroid insecticides that create a protective zone when burned. Use coils outdoors or in very well ventilated areas, on heat safe surfaces, and away from flammable materials. Keep them out of reach of children and pets. Electric mats and liquid vaporizers are suited for indoor rooms with closed windows and doors. Follow device instructions and allow adequate time for the product to work before bedtime.

Physical barriers still matter. Keep windows and doors screened. Consider a bed net if you sleep with windows open and live near vegetation or water. Fans help, especially in still air on balconies, patios, and at campsites. Combined use of repellent, clothing, and airflow cuts bite risk significantly.

How long the risk lasts as temperatures fall

Autumn risk ends after a true cold snap. Activity usually declines as afternoon highs fall below the mid teens. Once a first hard frost arrives, most adult mosquitoes die off in exposed areas. In parts of Japan with warmer coastal weather, mild spells can persist into November, and so do mosquitoes. In cooler regions, outdoor biting fades earlier, though some mosquitoes can shelter inside structures where temperatures are stable.

For planning, assume bite risk through at least October in much of Honshu and into November in milder southern areas. Store repellents and coils where you can find them quickly on warm weekends. Retailers often reduce insect control shelf space in fall, so consider buying an extra bottle of repellent beforehand if you expect outdoor events or travel.

Cool, dry days help. Choose seats away from shrubs, place a small fan on a table, and pick lighter color clothing. These simple tweaks lower the chance of a surprise bite during a walk under red leaves or at an autumn festival.

Mosquito borne disease in focus

Most mosquitoes in Japan are a nuisance rather than a source of serious illness. Even so, some species can carry viruses in certain conditions. Asian tiger mosquitoes are capable of spreading dengue and chikungunya where those viruses are present. House mosquitoes can spread other viruses in regions where they circulate. Japan maintains surveillance and responds quickly when risks change. Local transmission of dengue was documented in Tokyo in 2014, and control measures were taken.

Travel adds another layer. People returning from tropical or subtropical regions can be infected without knowing it. Guidance from public health agencies advises preventing mosquito bites for three weeks after returning from travel to avoid passing a virus to local mosquitoes. If you develop fever, headache, muscle or joint pain, or a rash after travel, seek medical care and share your travel history. Early diagnosis helps protect you and those around you.

Vaccines exist for some infections, such as Japanese encephalitis for people at risk, and for yellow fever in regions where it is required. There is no vaccine for many common mosquito spread viruses. Bite prevention is the main tool. That is why household water control, consistent repellent use, and sensible clothing choices make such a difference in autumn.

What to Know

- Mosquito activity peaks in early to mid autumn as temperatures drop into a mild range.

- Asian tiger mosquitoes bite during the day and breed in small containers near homes.

- House mosquitoes extend risk into the evening and at night, especially with open windows.

- Female mosquitoes need blood to produce eggs and live about a month, which drives aggressive biting in fall.

- Standing water in tiny places like plant saucers and bottle caps can produce many adults in one week.

- Use EPA registered repellents with DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus or PMD, or 2 undecanone as directed.

- Permethrin is for clothing and gear only, not skin, and coils require good ventilation and safe placement.

- Risk usually falls below 15 degrees Celsius and ends after a hard frost, but warm spells can extend activity into November.