A new look at the first human code

For generations, the story of writing began in ancient Mesopotamia around 3400 to 3200 BC with clay tablets covered in wedge shaped signs. A growing body of research now pushes an earlier chapter into view. Ice Age artists, active tens of thousands of years before cities rose on the Tigris and Euphrates, did more than paint powerful animals. Beside bison, horses, deer, salmon, and mammoths, they added small sequences of marks, especially dots, short lines, and a distinctive Y sign. A 2023 study proposes that those marks recorded time specific facts about animal behavior, an information system that would move the earliest proto writing back by at least ten millennia.

- A new look at the first human code

- What do the cave signs show?

- A lunar calendar in dots and lines

- Support, skepticism, and what counts as writing

- How this compares with Mesopotamian writing

- Deep roots of symbolic thought

- What the symbols might have meant

- Why the debate matters

- What researchers are doing next

- Highlights

The idea turns on a simple premise. If each dot or line stands for a lunar month, and the Y indicates the month of birth, then the sequences function like a compact almanac keyed to the spring. London based independent researcher Ben Bacon, working with academic collaborators, compiled hundreds of examples across European caves and portable objects. They found consistent associations between species and the number of marks, with the Y placed where gestation would end. Statistical tests, anchored to the life cycles of modern descendants, found strong matches. The marks would have helped hunter gatherers anticipate when herds gathered to mate, when calves would be born, and when salmon would surge up rivers, moments that shaped survival.

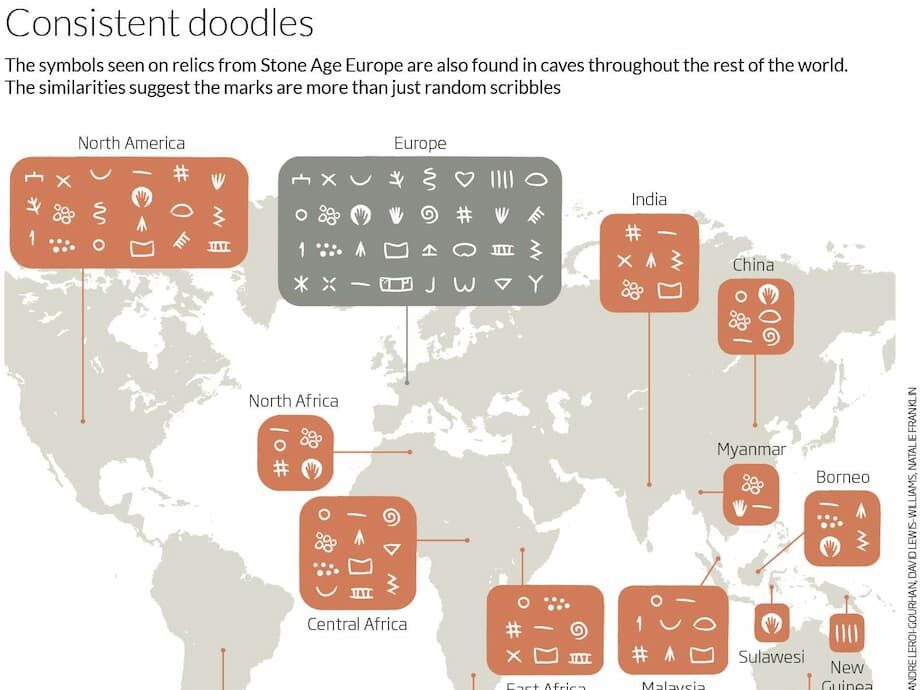

This new case sits alongside a decade of fieldwork by paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger. Her catalog of geometric signs in European caves, based on visits to 52 sites in France, Spain, Italy, and Portugal, identified a compact repertoire of 32 recurring symbols over a span of at least 30,000 years. Dots, lines, triangles, zigzags, grids and ladders, negative hands, penniforms shaped like feathers, and tectiforms that resemble a post with a roof appear again and again. The consistency suggests deliberate choices, not doodles, and a shared tradition that may have roots outside Europe.

What do the cave signs show?

Inside the painted chambers of Lascaux and Chauvet in France, Altamira in Spain, and many lesser known sites, simple signs accompany the animal scenes. Von Petzinger’s field notes and database suggest that while artists varied styles and scale, they drew from a small toolkit. A few symbols soared in popularity for a time then faded, like cultural trends. Penniforms appear to begin in northern France around 26,000 years ago and spread south. Hand stencils were common early on, often paired with dots. Later, thumb stencils and finger fluting, the parallel trails made by dragging fingers through soft deposits, pick up in frequency. These shifts hint at fashion, identity, or changing uses of the signs.

Geometric signs are not confined to cave walls. Archaeologists have found the same motifs on small portable items, including deer teeth strung into necklaces around 16,000 years ago. The portability matters. It suggests the signs moved with people, carried across landscapes, and communicated beyond a single ritual space. Research teams now report matches between many European symbols and marks recorded far beyond Europe. Surveys and archives point to similar shapes in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Australia, and North America. Early modern humans likely brought parts of this symbolic repertoire with them as they dispersed, then added and recombined signs over time.

Another striking pattern is sheer abundance. In many caves, geometric signs outnumber animal figures by at least two to one. The signs occupy entrances, deep chambers, and connecting passages. They appear alone and in clusters, sometimes in tight association with specific species. They are painted, engraved, or pecked into stone. The restricted number of types over so long a period, across many regions, argues for meaning that was widely understood by the people who made and saw them.

A lunar calendar in dots and lines

Ben Bacon’s work sought to decode the short sequences. He began by counting. From published images and site surveys, he compiled a database of 606 animal depictions paired with dots or lines, and another 256 with a Y added to the sequence. No sequence exceeded 13 marks. The team proposed that the sequence counted lunar months after a yearly reset in spring, when snow and ice receded and rivers thawed. In this scheme, three marks beside a horse would indicate that mating usually began three months after spring. Five marks near a mammoth would point to a later start. The Y would align with birthing, a practical signal for hunters tracking vulnerable newborns and foragers forecasting seasonal journeys of herds and fish.

To test the idea, the researchers compared the counts for Ice Age species to the mating and birthing cycles of present day relatives, including horses, bison, red deer, reindeer, and salmon. Durham University psychologist Robert Kentridge evaluated the data and reported strong correlations between the number of marks, the position of the Y, and the expected months for mating and birth. Mathematician Tony Freeth, known for breakthroughs on the ancient Greek Antikythera mechanism, contributed to the model that treated each mark as a lunar month rather than a single day.

Ethnographic records strengthen the plausibility. Many Indigenous hunter gatherer societies have counted moon cycles to plan hunting and fishing. The Yurok of northern California timed the construction of fish weirs for migrating steelhead using a lunar count. The Yami of Taiwan still follow a lunar calendar to target flying fish. A simple month by month count, anchored to a spring reset, fits the needs of Ice Age foragers who depended on recurring animal behavior. It would be a compact, portable, and teachable system that spreads easily within groups.

Bacon and his collaborators describe the marks as proto writing, a step between notation and fully expressive writing. The signs do not encode grammar or represent speech. They function more like a numeric schedule tied to the natural calendar, a way to record and predict patterns in the world.

Support, skepticism, and what counts as writing

Experts welcome fresh thinking about the marks, while urging restraint on bold claims. Paleoanthropologist Melanie Chang notes that people of the Upper Paleolithic had the cognitive capacity to write and to track time, yet cautions that the current results do not rule out other readings of the same data. Different sites, separated by centuries and cultures, might have used similar marks in different ways. The current model, she argues, needs more exhaustive testing.

Paleolithic archaeologist April Nowell agrees that the approach is creative, but points out that the team analyzed only three recurring signs, out of at least 32 documented across Europe. That leaves most symbols without a proposed meaning. A deeper pass through the full repertoire, on walls and on portable objects, would test whether the lunar scheme holds up beyond the most common marks. The team says more papers are in progress to do just that.

Von Petzinger, whose surveys defined much of the modern dataset, supports the idea that many dots and lines are a form of notation tied to counting. She stops short of calling the marks writing. In her view, writing, even proto writing in a narrow sense, relates to representing spoken language through a sequence of signs that can stand for sounds or words. The cave marks behave more like graphic communication, information carried by a symbol that does not require translation into speech.

French prehistorian Jean Clottes is skeptical that the signs point toward writing at all, stressing that the marks often sit intertwined with animal figures, which he sees as the primary subject. In a different vein, MIT linguist Cora Lesure and co authors argue that drawing and language share core cognitive mechanisms. On that view, cave and rock art could be treated as a modality of linguistic expression, and the abstract symbols might be an elaboration on that cognitive step. The field remains divided, which is common when data are old, fragmentary, and context is sparse.

How this compares with Mesopotamian writing

The debate gains clarity when compared to the later invention of writing in southwest Asia. In the Uruk world of the fourth millennium BC, administrators used clay tokens, bullae, and cylinder seals to count flocks, textiles, grain, and jars. From about 3350 to 3000 BC, a system known as proto cuneiform appears. It is a large set of pictorial and abstract signs impressed or incised in clay to label quantities, goods, and officials. True cuneiform, a full writing system, follows soon after. It could record names, actions, and later complex texts in Sumerian and Akkadian.

New research suggests that imagery on cylinder seals helped generate the inventory of signs that became proto cuneiform. Archaeologists compared the motifs rolled into wet clay, such as fringed cloth or vessels held in a net, with signs on early tablets. In several cases, shapes and meanings match. One sign known in scholarship as ZATU639 resembles a bull motif seen on seals and appears in similar accounting contexts. The result implies a decentralized process, where many clerks, craftspeople, and traders across a region contributed to a shared symbol set that gradually stiffened into a formal script.

Mesopotamian proto cuneiform differs from Ice Age marks in two key ways. It is younger by tens of millennia and it was designed for bureaucracy. The earliest tablets represent accounting entries and inventories, not myths or narratives. The Ice Age sequences, if they track months and births, behave like field notes for foragers. They likely lack grammar and syntax. Both, however, show a human drive to stabilize memory with marks, to move knowledge from minds into durable signs that others can read later.

Deep roots of symbolic thought

The capacity to make and understand abstract marks is older than the European caves. In South Africa’s Blombos Cave, a 70,000 years old piece of ochre bears a deliberate cross hatched design, often described as the earliest known drawing. On Java, a freshwater shell etched by Homo erectus about 500,000 years ago carries a zigzag pattern made with a sharp tool. Neanderthals may also have made graphic marks, including cross hatching at Gibraltar and red hand stencils in Spain that may predate the arrival of Homo sapiens. These finds do not count as writing. They do show that hominins experimented with pattern and symbol long before the Ice Age masterworks of Europe.

Within the European record, trends over time hint at social networks and movement. Von Petzinger sees some signs begin in one region and spread, then fade as tastes change or groups merge. The preference for red ochre, sometimes heat treated to improve color, points to technical knowledge and planning. Hand stencils were made by spit painting, blowing pigment over a hand pressed against the wall to leave a negative impression. The frequent pairing of hands with dots, and later with thumb stencils or finger fluting, may reflect changing practices or layered meanings that we can track but not yet read.

What the symbols might have meant

Working meanings for most signs remain uncertain. Hypotheses range widely, and more than one could be true depending on place and time. Some archaeologists read the marks as hunting magic or ritual, with symbols tied to clan identity, success, or control of a site. Others see gender associations, with hooks, lines, and angles mapped to male symbols and ovals or circles to female concepts. Cognitive scholars argue that some geometric forms match visual effects seen in altered states, which could help explain repeated patterns. A more prosaic reading sees the signs as a practical code for planning, learned by adolescents and adults, and taught across generations.

Combinations of signs suggest that some marks modified others, like adjectives applied to a noun. A hand stencil beside a run of dots might mark a person’s participation in a count. A penniform next to a deer could identify a location or a group associated with that place. Portable objects carry the code beyond the cave. Engraved teeth or decorated stones could serve as reminders in daily life, enviable tools for leaders who needed to line up a large group for a seasonal move.

Why the debate matters

Far from a dry argument over terminology, the discussion touches on how humans became a species that outsources memory. When people record time sensitive facts about the world, even with very simple marks, they reduce the burden on individual recall and increase group resilience. A compact calendar and sign set would have helped bands coordinate movement, share news, and train young people. That edge compounds across generations. It is the same logic that later drove clay tablets, tally sticks, quipu, alphabets, and digital code.

Reframing Ice Age signs as information storage also narrows the cultural distance between those people and us. Many of the choices they made, from standardizing a small set of symbols to reusing them across regions, mirror how communities build and maintain shared conventions. The result challenges the idea of a sudden divide between prehistory and history. Writing did not appear from a vacuum. It grew from earlier habits of marking and remembering.

What researchers are doing next

The case for a lunar month system is not closed. Bacon and colleagues say they will expand their analysis to more signs, check the model across wider regions and time windows, and test sequences against additional species. They also aim to understand whether the order of marks carries extra meaning beyond counts and birth indicators. Other teams are building larger databases of cave and rock art, including portable objects, so that recurring combinations and regional quirks can be assessed more rigorously.

New technology may unlock more evidence. Many coastal caves used by Ice Age people are now underwater. Marine archaeologists are deploying robots and advanced imaging to search drowned entrances and chambers. High resolution 3D scans, improved dating methods, and pigment analysis will refine timelines and attribute authorship more securely. Even if the exact meanings remain out of reach, the direction of research points to a richer story about the origins of graphic communication and the long arc that led to writing.

Highlights

- Researchers argue that Ice Age dots, lines, and Y signs tracked lunar months and animal births, an early information system at least 20,000 years old.

- Ben Bacon’s team compiled 606 animal images with marks and 256 with a Y, finding strong correlations with known mating and birthing cycles.

- Von Petzinger’s field surveys identified 32 recurring geometric signs used across Europe for 30,000 years, many also seen on portable objects.

- Experts are split on whether to call the marks proto writing or notation, with some favoring the term graphic communication.

- Comparisons with Mesopotamian proto cuneiform show different aims: Ice Age marks likely aided foragers, while early tablets served administration.

- Evidence from Blombos Cave, Java, and possible Neanderthal engravings points to deep roots for symbolic thought long before European cave art.

- Next steps include testing more signs, expanding databases beyond Europe, and exploring submerged caves with new imaging tools.