Dali: The Bohemian Refuge Drawing Disenchanted Chinese Youth

Nestled between the lush slopes of the Cangshan mountains and the tranquil waters of Lake Erhai, Dali has emerged as a sanctuary for a new generation of Chinese youth seeking escape from the relentless pressures of urban life. Once a remote outpost in Yunnan province, Dali is now synonymous with new beginnings, alternative lifestyles, and a spirit of freedom that stands in stark contrast to the conformity and competition of China’s megacities.

- Dali: The Bohemian Refuge Drawing Disenchanted Chinese Youth

- Why Are Young Chinese Fleeing the Cities?

- Who Are Dali’s Newcomers?

- How Has Dali Changed Under the Bohemian Influx?

- Dali in the Broader Context of Chinese Social Change

- Personal Journeys: Seeking Inner Peace in Dali

- Challenges and the Future of Dali’s Bohemian Dream

- In Summary

For many, Dali represents more than just a picturesque retreat. It is a place to leave behind the past, redefine one’s future, and embrace a slower, more intentional way of living. As Tanya Guo, a 26-year-old who left Beijing for Dali, put it:

“It wasn’t the life I wanted. The question of moving somewhere by choice rather than necessity came up regularly in conversations with my friends. Whenever this topic is discussed in China, Dali always comes up.”

Why Are Young Chinese Fleeing the Cities?

China’s rapid urbanization over the past four decades has transformed the country, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty and creating sprawling metropolises like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Yet, for many young people, the promise of city life has given way to disillusionment. Skyrocketing housing costs, grueling work schedules, and intense social competition have left many feeling trapped in what is known as “involution” (neijuan)—a term describing the exhausting, self-perpetuating cycle of overwork and diminishing returns.

This sense of burnout has given rise to a new cultural phenomenon: “lying flat” (tangping). The phrase, which went viral on Chinese social media, encapsulates a quiet rebellion against the relentless pursuit of success. Instead of climbing the corporate ladder or chasing material wealth, some young Chinese are choosing to opt out, seeking fulfillment in simplicity and self-care. Dali, with its mild climate, stunning scenery, and laid-back atmosphere, has become the unofficial capital of this movement—sometimes even nicknamed “Dalifornia” for its relaxed, countercultural vibe.

As one urban escapee wrote after moving to Dali:

“Many others came to Dali for similar reasons, seeking personal change away from China’s cities. Dali was jokingly called the ‘capital of lying flat’ or ‘Dalifornia’ for its good weather and relaxed vibe. The back-to-the-land trend reversed decades of urbanization, as some city-born Chinese wanted to return to rural roots.”

Who Are Dali’s Newcomers?

The influx of newcomers to Dali is as diverse as the city itself. Among the arrivals are:

- Disenchanted office workers and recent graduates burned out by city life

- Artists, musicians, and writers seeking creative inspiration

- Environmentalists and spiritual seekers drawn to nature and alternative communities

- Political dissidents and digital nomads looking for greater personal freedom

- Retirees and families in search of a healthier, slower-paced lifestyle

Many of these newcomers are not just escaping the pressures of capitalism, but also seeking refuge from the tightening grip of state control in China’s major cities. In Dali, they find a community of like-minded individuals—hippies, yuppies, bohemians, homeschoolers, Taoists, Buddhists, and more—each carving out their own version of the good life.

British writer Alec Ash, who chronicled his first year in Dali in the memoir “The Mountains Are High,” describes the city as a place where “bohemian hippies and political dissidents are rejecting the worst parts of modernity and living more simply, in tune with the natural world and away from authoritarian power.”

How Has Dali Changed Under the Bohemian Influx?

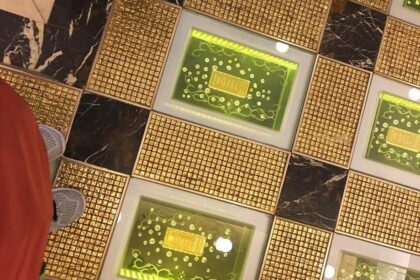

Dali’s transformation from a tranquil settlement to a trendy destination has not been without consequences. Over the past two decades, the city has become a magnet for tourists and migrants alike, leading to rapid development, rising rents, and growing concerns about environmental degradation.

Longtime residents and early migrants have witnessed the city’s gentrification firsthand. As property developers move in and infrastructure expands, the cost of living has soared, forcing many locals and small business owners out of Dali’s historic Old Town. The closure of beloved local establishments, replaced by generic tourist shops, has sparked debates about the loss of authenticity and the sustainability of Dali’s bohemian reputation.

Experimental musician Wu Huanqing, who moved to Dali in 2003, reflects on the city’s evolution:

“While I value the new opportunities for musicians, I recall a time when Dali was more laid-back and connected. Modernity and tradition can coexist, but we must respect and learn from the local ecosystem.”

Painter and café owner Rong Jie, who renovated a traditional Bai-style house into a café, echoes this sentiment:

“Some newcomers criticize local construction workers, but the issues arise when workers are asked to build in unfamiliar modern styles. We should preserve traditional architecture and culture.”

The Environmental and Social Costs

The boom in tourism and migration has also brought environmental challenges. Pollution, overdevelopment, and strain on local resources threaten the very landscapes that drew newcomers to Dali in the first place. Efforts to balance growth with preservation are ongoing, with initiatives like the Dali Bed Sheet Art District providing affordable studio space for artists and promoting sustainable development.

Dali in the Broader Context of Chinese Social Change

Dali’s rise as a bohemian refuge is part of a larger story about youth migration and social transformation in China. For decades, the dominant narrative was one of rural-to-urban migration, as millions left the countryside in search of better opportunities in the cities. This movement fueled China’s economic miracle but also created new social challenges, from the plight of “left-behind children” to the rigidities of the hukou (household registration) system that restricts access to services for migrants.

Now, a reverse migration is underway—albeit on a smaller scale—as some urbanites seek to reconnect with rural roots or simply escape the pressures of city life. This trend is not unique to China; similar movements have been observed in other countries as well, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of remote work.

Yet, as writer Pallavi Aiyar notes in her review of recent books on Chinese society, the significance of this “private revolution” is still up for debate. While some see it as a meaningful act of resistance or self-discovery, others question whether opting out of the system constitutes real political change. The stories of Dali’s newcomers are often marked by a blend of nostalgia, idealism, and pragmatism—a search for meaning in a rapidly changing world.

The Role of Yunnan’s Diversity

Dali’s appeal is also rooted in the unique cultural and ethnic diversity of Yunnan province. With 26 recognized ethnic minorities, Yunnan is one of China’s most multicultural regions. This diversity is reflected in Dali’s architecture, cuisine, music, and daily life, offering newcomers a sense of openness and possibility that can be hard to find elsewhere in China.

As the New York Times observed in a historical context, Yunnan’s cities like Kunming and Dali have long been places of exile and refuge for those seeking a different pace of life or a break from the mainstream. The region’s laid-back, bohemian atmosphere continues to attract artists, intellectuals, and free spirits from across China and beyond.

Personal Journeys: Seeking Inner Peace in Dali

For many who make the journey to Dali, the move is as much about internal transformation as it is about changing one’s surroundings. The mountains, lakes, and valleys of Dali offer a backdrop for self-reflection, healing, and personal growth. Yet, as some discover, true peace cannot be found solely in a change of scenery.

One urban escapee recounted their experience climbing Cangshan, the mountain overlooking Dali:

“I had projected significance onto Dali and the mountain, believing I’d be restored there. But isolation is internal; the answers weren’t in the hills. I started cooking, gardening, and spending time outdoors. Hobbies like music, running, archery, and tai chi filled my days. But changing location wasn’t enough; I needed to change my mind.”

For others, Dali is a place to experiment with new ways of living—homeschooling children, starting small businesses, practicing meditation or traditional arts, or simply enjoying the freedom to “lie flat” for a while. The city’s spirit of openness and experimentation continues to draw those seeking respite from the demands of modern China.

Challenges and the Future of Dali’s Bohemian Dream

As Dali’s popularity grows, so do the challenges facing its community. Rising costs, environmental pressures, and the risk of losing the very qualities that made Dali attractive in the first place are all pressing concerns. The tension between preserving local culture and accommodating newcomers is a delicate balance, requiring thoughtful engagement from both residents and migrants.

Yet, despite these challenges, Dali remains a symbol of possibility—a place where individuals can redefine success, reconnect with nature, and build new forms of community. Whether as a temporary refuge or a permanent home, Dali’s allure endures, offering lessons in resilience, adaptation, and the enduring human search for meaning.

In Summary

- Dali has become a haven for young Chinese seeking escape from urban pressures and a more meaningful life.

- The city’s appeal lies in its natural beauty, mild climate, and reputation for openness and alternative lifestyles.

- Newcomers to Dali include artists, digital nomads, spiritual seekers, and those burned out by city life.

- The influx has brought both opportunities and challenges, including gentrification, rising costs, and environmental concerns.

- Dali’s story reflects broader trends in Chinese society, including the rise of “lying flat” culture and reverse migration from cities to rural areas.

- The future of Dali’s bohemian dream depends on balancing growth with preservation and maintaining the city’s unique spirit.