The Last Santoor Maker: A Vanishing Art in the Heart of Kashmir

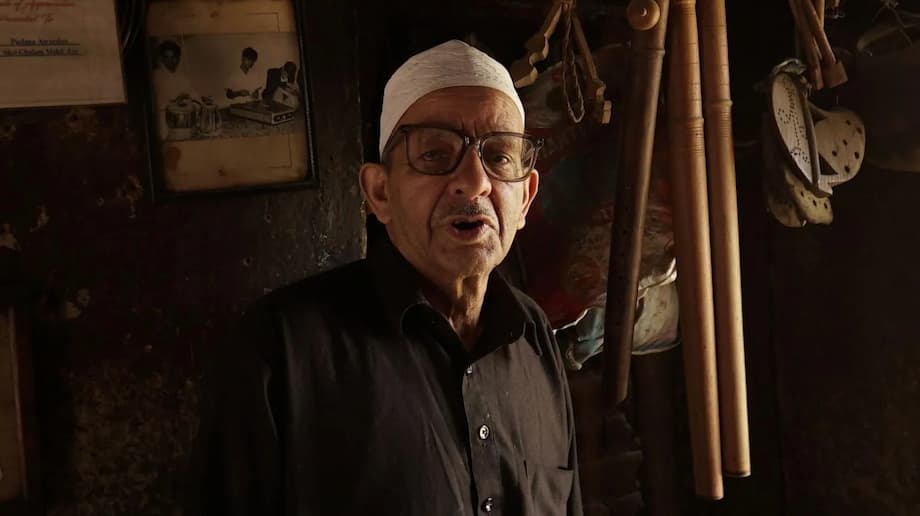

In the labyrinthine lanes of Srinagar’s old city, a dimly lit workshop stands as a silent witness to centuries of musical tradition. Here, surrounded by the scent of aged walnut wood and the quiet hum of memory, Ghulam Mohammad Zaz—now in his eighties—continues to handcraft the santoor, a 100-stringed instrument that has long been the soul of Kashmiri music. Zaz is widely believed to be the last artisan in Kashmir, and perhaps all of India, who still makes the santoor entirely by hand, carrying forward a family legacy that stretches back at least eight generations.

- The Last Santoor Maker: A Vanishing Art in the Heart of Kashmir

- What Is the Santoor and Why Is It So Important to Kashmir?

- How Did the Santoor Become a Global Instrument?

- Inside the Workshop: The Art and Science of Santoor Making

- Recognition and the Burden of Legacy

- The Broader Crisis: Traditional Crafts at Risk

- Can the Santoor Be Saved?

- In Summary

The story of Zaz is not just about one man’s dedication to his craft. It is a poignant reflection of the challenges facing traditional artisans in a rapidly modernizing world, and a testament to the enduring power of music as a vessel for cultural identity.

What Is the Santoor and Why Is It So Important to Kashmir?

The santoor is a trapezoid-shaped hammered dulcimer, played with a pair of curved mallets called mezrabs. Its crystalline, bell-like tones have echoed through Kashmiri valleys for centuries, making it an integral part of the region’s folk and Sufi musical traditions. The instrument’s name comes from the Persian word for “a hundred strings,” and its origins can be traced back to Persia and Central Asia. Over time, the santoor traveled across continents, evolving into distinct forms in Iran, China, and Europe. But it was in Kashmir that the instrument found a unique voice, becoming central to Sufiana Mausiqi (Kashmiri Sufi music) and folk performances.

In its traditional Kashmiri form, the santoor is made from seasoned mulberry or walnut wood, with 100 strings arranged in groups and stretched over 25 meticulously crafted bridges. The hollowed body acts as a resonator, producing a sound that is both haunting and uplifting. The instrument’s construction is a blend of precision, patience, and intuition—a process that can take months to complete.

The Zaz Family Legacy

For over three centuries, the Zaz family has been synonymous with the finest santoors and rababs in Kashmir. Ghulam Mohammad Zaz learned the craft from his father and grandfather, making his first santoor at the age of 15. His ancestors were once summoned by local kings to build instruments that could “soothe hearts,” and their creations have been played by the valley’s most distinguished musicians. Zaz’s workshop, with its blackened walls and worn tools, is a living museum of Kashmiri musical heritage.

How Did the Santoor Become a Global Instrument?

While the santoor’s roots are deeply embedded in Kashmiri culture, its journey onto the world stage is largely credited to two maestros: Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and Pandit Bhajan Sopori. Both musicians, who played instruments crafted by Zaz and his family, revolutionized the santoor’s role in Indian classical music. Sharma, in particular, modified the instrument by adding more strings, redesigning bridges for richer resonance, and developing new playing techniques. These innovations expanded the santoor’s tonal range and expressive capabilities, allowing it to hold its own alongside sitar and sarod in classical concerts and even Bollywood soundtracks.

“If my craft is alive today, it is because legends like Pt Sharma and Pt Sopori infused new life into the santoor,” Zaz told Moneycontrol. “They both played the santoor throughout the world to make it a famous musical instrument.”

Despite this global recognition, the demand for handcrafted santoors has dwindled in recent years. Machine-made instruments, which are cheaper and quicker to produce, have flooded the market. Meanwhile, younger generations in Kashmir are increasingly drawn to hip hop, rap, and electronic music, leaving traditional forms like Sufiana Mausiqi struggling for relevance.

Inside the Workshop: The Art and Science of Santoor Making

Step into Zaz’s workshop in Zaina Kadal, and you enter a world where time seems to stand still. The process of making a santoor is as much about listening as it is about craftsmanship. “They taught me not just how to make an instrument but how to listen—to the wood, the air, and the hands that would play it,” Zaz recalls of his father and grandfather.

The journey begins with selecting the right wood, which must be aged and seasoned for at least four years to achieve the desired tonal quality. Zaz often uses mulberry or walnut, both prized for their resonance. The wood is carefully dried, cut, and joined at precise angles. The hollow body is carved out, and the surface is finished with a homemade polish to ensure the keys don’t become slippery. The bridges—25 in total—are shaped and placed with meticulous care, and over 100 strings are added, each tuned to perfection. The entire process can take two to three months, depending on the artisan’s mood and energy.

“The wood speaks to me,” Zaz told Indian Express. “I don’t use any tool for measurements, relying on my heart and mind.”

In the past, the Zaz family would decorate their instruments with ivory and hangul (Kashmiri stag) horns, but today, they use sheep horn due to the scarcity of traditional materials. The stick used to play the santoor, called qalam, is made from a special dried wood found only in Kashmir, which is now nearly impossible to source.

Why Is the Craft Dying?

The decline of santoor making in Kashmir is the result of several converging factors:

- Changing Musical Tastes: Younger generations are more interested in contemporary genres, leading to a shrinking audience for traditional music.

- Economic Pressures: Machine-made instruments are cheaper and more accessible, undermining the market for handcrafted santoors.

- Scarcity of Raw Materials: The specific woods and materials required for traditional santoor making are increasingly hard to find, with some (like elephant tusk) now banned.

- Lack of Apprentices: With no one in his family or community willing to learn the craft, Zaz fears he will be the last in his line.

“The new generation is not interested in playing traditional musical instruments,” Zaz laments. “They prefer a different genre of music because they do not understand the value of traditional music.”

Recognition and the Burden of Legacy

Despite the challenges, Zaz’s work has not gone unnoticed. In 2023, he was awarded the Padma Shri, India’s fourth-highest civilian honor, for his contribution to the arts. The recognition brought him pride, but also a sense of bittersweet regret. “I would have been happier had the award come earlier, when my grandfather, father, and uncles—those who shaped me as a craftsman—could have witnessed it,” he told The New Indian Express.

Photos in his workshop show Zaz receiving the award from President Droupadi Murmu, as well as images of maestros Shiv Kumar Sharma and Bhajan Sopori performing with his instruments. Yet, for Zaz, true fulfillment comes not from fame or accolades, but from the act of creation itself. “This is not just woodwork,” he says. “It is poetry. A language. A tongue I give to the instrument. I hear the santoor before it plays. That is the secret. That is what must be passed on.”

Economic Realities and the Search for a Successor

For decades, Zaz’s craft provided a stable livelihood. He was able to build a home, educate his three daughters, and gain a reputation that brought clients from across India and abroad. But as he grows older and raw materials become scarcer, he now makes only a handful of instruments each year. Much of his business comes from tourists and foreign customers, and he supplements his income by repairing other stringed instruments.

Despite offers of government grants and promises of apprentices, Zaz remains skeptical. “I am not looking for fame or charity. What I truly want is someone to carry the art forward. Not for the money, not for the cameras, but for the music.”

The Broader Crisis: Traditional Crafts at Risk

The plight of Ghulam Mohammad Zaz is emblematic of a wider crisis facing traditional crafts in Kashmir and across India. The region, renowned for its wood carving, papier-mâché, pashmina shawls, and intricate embroidery, has seen many of its artisanal traditions decline in the face of modernization and mass production. Crafts that once defined Kashmiri identity are now at risk of fading into obscurity.

Other master artisans—like Ali Mohammad Giru (khatamband woodwork), Mohammad Hanief (turquoise jewelry), and Bashir Ahmad Dar (carpet weaving)—share similar stories of dwindling apprenticeships and uncertain futures. While some crafts, like kani shawl weaving, have seen a modest resurgence thanks to renewed interest and government support, most remain endangered.

“The survival of these ancient crafts is now in jeopardy as the tradition of passing down skills through generations fades,” notes Sahapedia, a platform dedicated to Indian heritage.

Can the Santoor Be Saved?

Efforts to preserve the santoor and other traditional crafts have included government grants, handicraft department initiatives, and increased media attention. Social media influencers and journalists have visited Zaz’s workshop, sharing his story with a global audience. Yet, as Zaz himself points out, publicity alone is not enough. Real preservation requires a new generation willing to dedicate themselves to the painstaking art of instrument making.

Some experts argue that integrating traditional crafts into school curricula, providing apprenticeships, and ensuring access to raw materials could help revive interest among young people. Others suggest that collaborations with contemporary musicians and designers might breathe new life into old forms.

But the challenge remains daunting. As Zaz spends his days beside unfinished santoors, he is acutely aware of the fragility of his legacy. “Wood and music, both die if you don’t give them time,” he says. “I want someone who truly loves the craft to take it forward.”

In Summary

- Ghulam Mohammad Zaz is widely regarded as the last traditional santoor maker in Kashmir, representing an unbroken family legacy of over 300 years.

- The santoor, a 100-stringed hammered dulcimer, is central to Kashmiri Sufi and folk music and has gained global recognition thanks to maestros like Shiv Kumar Sharma and Bhajan Sopori.

- Handcrafted santoor making is a meticulous, months-long process requiring rare materials, patience, and deep musical intuition.

- Modern musical tastes, economic pressures, scarcity of raw materials, and lack of apprentices threaten the survival of the craft.

- Zaz was awarded the Padma Shri in 2023, but laments the lack of a successor to carry on his family’s tradition.

- The decline of santoor making reflects a broader crisis facing traditional crafts in Kashmir and across India.

- Preserving this heritage will require more than recognition—it demands active support, education, and a new generation willing to embrace the art for its own sake.