The Emergency: A Turning Point in Indian Democracy

In June 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency in India, marking one of the most controversial and transformative periods in the nation’s post-independence history. Civil liberties were suspended, political opposition was jailed, and the press was muzzled. While the Emergency is often remembered for its overt authoritarianism, a lesser-known but equally significant development was the Congress government’s covert push to fundamentally alter India’s system of governance—from a parliamentary democracy to a centralized presidential system.

- The Emergency: A Turning Point in Indian Democracy

- Why Did Indira Gandhi’s Government Consider a Presidential System?

- The Forty-second Amendment: The Shadow of Presidentialism

- The Aftermath: Reversal and Resilience of Parliamentary Democracy

- Why Did the Presidential System Fail to Take Root?

- Broader Implications: The Legacy of the Emergency and the Debate on Governance

- In Summary

This article explores the origins, ambitions, and ultimate failure of this push, drawing on the latest historical research and contemporary accounts. It examines how the Emergency became a crucible for constitutional experimentation, the motivations behind the move toward presidentialism, and the enduring impact on India’s political landscape.

Why Did Indira Gandhi’s Government Consider a Presidential System?

India’s original Constitution, adopted in 1950, established a parliamentary democracy modeled on the British system. The Prime Minister, as head of government, was accountable to an elected legislature, while the President served as a largely ceremonial head of state. This system was designed to ensure checks and balances, with an independent judiciary and a free press acting as additional safeguards.

By the mid-1970s, however, the system was under strain. The Congress Party’s dominance was eroding, coalition politics were on the rise, and the judiciary had begun to assert itself as a check on executive power. Indira Gandhi’s own position was threatened by a court ruling that invalidated her election, and mass protests were mounting against her government. In this context, some of Gandhi’s closest advisors and party loyalists began to argue that India’s parliamentary system was ill-suited to the country’s needs.

BK Nehru, a seasoned diplomat and Gandhi confidant, articulated this view in a letter written in September 1975. He described the Emergency as a “tour de force of immense courage and power produced by popular support” and argued that parliamentary democracy had failed to deliver decisive governance. Nehru advocated for a directly elected president, free from the constraints of legislative dependence, who could take “tough, unpleasant and unpopular decisions” in the national interest. The model he cited was Charles de Gaulle’s France, where the Fifth Republic had replaced parliamentary instability with a strong executive presidency.

These ideas resonated with many in the Congress leadership, who saw the judiciary as “obstructionist” and Parliament as a “symbolic chorus.” The chief minister of Haryana was especially blunt, suggesting that Indira Gandhi should simply be made “President for life.”

What Would the New System Have Looked Like?

The proposals that emerged from these discussions were radical. Nehru envisioned a single, seven-year presidential term, proportional representation in Parliament and state legislatures, a judiciary with curtailed powers, and a press reined in by strict libel laws. Fundamental rights—such as equality and freedom of speech—would be stripped of their justiciability, meaning citizens could not challenge violations in court.

A secret document titled “A Fresh Look at Our Constitution: Some Suggestions” was drafted and circulated among trusted advisors. It proposed a president with powers exceeding even those of the American president, including control over judicial appointments and legislation. A new “Superior Council of Judiciary,” chaired by the president, would interpret laws and the Constitution, effectively neutering the Supreme Court.

Indira Gandhi authorized further exploration of these ideas but remained publicly non-committal. She instructed her aides not to give the impression that the proposals had her official endorsement. Nevertheless, the momentum for constitutional change was real and growing within the Congress Party.

The Forty-second Amendment: The Shadow of Presidentialism

While the push for a full presidential system never crystallized into a formal proposal, its influence was unmistakable in the Forty-second Amendment Act of 1976. Passed at the height of the Emergency, this amendment represented the most sweeping set of constitutional changes in India’s history.

The Forty-second Amendment:

- Expanded Parliament’s powers at the expense of the judiciary and the states

- Made it significantly harder for the Supreme Court to strike down laws, requiring supermajorities of five or seven judges

- Attempted to dilute the “basic structure doctrine,” which limited Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution

- Granted the federal government sweeping authority to deploy armed forces in states and declare region-specific Emergencies

- Extended President’s Rule (direct federal rule) in states from six months to a year

- Placed election disputes beyond the reach of the judiciary

Though not a presidential system in name, the amendment carried its “genetic imprint”—a powerful executive, a marginalized judiciary, and weakened checks and balances. The Statesman newspaper warned that “by one sure stroke, the amendment tilts the constitutional balance in favour of the parliament.”

Congress Loyalists and the Cult of Leadership

During this period, Gandhi’s loyalists went further than even the official proposals. Defence Minister Bansi Lal called for “lifelong power” for Gandhi as prime minister, while Congress members in Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh unanimously demanded a new constituent assembly to rewrite the Constitution. The prime minister, reportedly taken aback by the extremity of these suggestions, chose instead to expedite the passage of the amendment bill through Parliament.

By December 1976, the Forty-second Amendment had been passed by both houses of Parliament, ratified by 13 state legislatures, and signed into law by the president. The changes fundamentally altered the balance of power in India’s constitutional system, even if the full presidential model was never adopted.

The Aftermath: Reversal and Resilience of Parliamentary Democracy

The Emergency ended abruptly in 1977, when Indira Gandhi called elections and suffered a shock defeat. The Janata Party, a coalition of anti-Gandhi forces, came to power and moved quickly to undo the authoritarian legacy of the Emergency. Through the Forty-third and Forty-fourth Amendments, the new government rolled back key provisions of the Forty-second, restoring judicial review and democratic checks and balances.

However, the Janata Party’s tenure was short-lived, plagued by internal divisions and leadership struggles. By January 1980, Gandhi was swept back to power, and the Congress Party once again dominated Indian politics. The idea of a presidential system, though dormant, was not dead.

Renewed Flirtation with Presidentialism

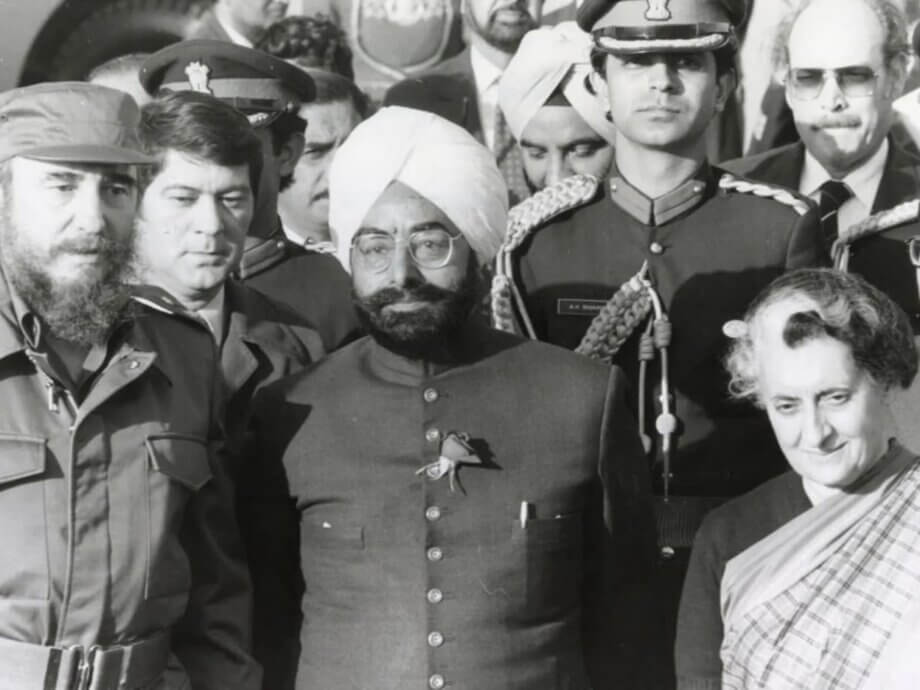

In 1982, as President Sanjiva Reddy’s term was ending, Gandhi seriously considered stepping down as prime minister to become president of India. Her principal secretary later revealed that she was “very serious” about the move, seeing the presidency as a way to deliver “shock treatment” to her party and rejuvenate its leadership. Ultimately, Gandhi chose instead to elevate her loyal home minister, Zail Singh, to the presidency, maintaining her own position as prime minister while ensuring continued influence over the office of president.

The desire for a presidential system within the Congress Party persisted even after Gandhi’s assassination in 1984. Senior minister Vasant Sathe launched a nationwide debate advocating a shift to presidential governance, but the conversation faded with Gandhi’s death. India remained a parliamentary democracy, shaped by the complex political dynamics and institutional resilience of the time.

Why Did the Presidential System Fail to Take Root?

Despite serious consideration and some institutional changes, India never made the leap to a presidential system. Several factors contributed to this outcome:

- Political Caution: Indira Gandhi, though a tactical and ambitious leader, was careful not to overreach. She authorized exploration of presidential ideas but stopped short of publicly endorsing them, perhaps sensing the risks of radical change.

- Lack of National Consensus: While some Congress leaders were enthusiastic, others—especially outside the party—were skeptical or opposed. M. Karunanidhi, the non-Congress chief minister of Tamil Nadu, was notably unimpressed by the proposals.

- Institutional Inertia: India’s parliamentary system, with its deep roots in the independence movement and its symbolic value as a democratic model, proved “sticky.” Even after the Emergency, the system rebounded, and attempts to centralize power were rolled back.

- Public Backlash: The excesses of the Emergency, including the suspension of civil liberties and the centralization of power, generated widespread public discontent. The 1977 election was, in many ways, a referendum on authoritarianism, and the electorate decisively rejected it.

Historian Srinath Raghavan, whose research has brought these episodes to light, argues that the push for a presidential system was primarily a tactical move by Gandhi to consolidate her power. “The aim was to reshape the system in ways that immediately strengthened her hold on power. There was no grand long-term design—most of the lasting consequences of her rule were likely unintended,” Raghavan told the BBC. “During the Emergency, her primary goal was short-term: to shield her office from any challenge. The Forty-second Amendment was crafted to ensure that even the judiciary couldn’t stand in her way.”

Broader Implications: The Legacy of the Emergency and the Debate on Governance

The Emergency and the flirtation with presidentialism left a lasting imprint on Indian politics. The episode exposed the vulnerabilities of the parliamentary system to executive overreach, but it also demonstrated the resilience of democratic institutions. The judiciary’s eventual reassertion of independence, the restoration of civil liberties, and the return to competitive elections all underscored the strength of India’s constitutional order.

Debate over the merits of parliamentary versus presidential systems continues in India to this day. Proponents of a presidential system argue that it would provide stable, decisive leadership and reduce the chaos of coalition politics. Critics warn that it could undermine the pluralism and checks and balances that are essential to India’s democracy.

Websites and commentators advocating for constitutional reform often cite the Emergency as a cautionary tale, warning against the dangers of unchecked executive power. The episode is also invoked in contemporary debates about the balance between majority rule and minority rights, the role of the judiciary, and the need for institutional safeguards.

In Summary

- During the Emergency (1975-77), Indira Gandhi’s government seriously considered transitioning India from a parliamentary to a presidential system, inspired by France’s Fifth Republic.

- Proposals included a directly elected president with sweeping powers, a marginalized judiciary, and a weakened Parliament, but these ideas never became formal policy.

- The Forty-second Amendment Act of 1976 reflected many of these ambitions, centralizing executive power and limiting judicial review.

- After the Emergency, the Janata Party government rolled back many authoritarian provisions, restoring democratic checks and balances.

- Indira Gandhi briefly considered becoming president herself in 1982, but ultimately chose to remain prime minister and appointed a loyalist as president.

- India’s parliamentary system survived, thanks to political caution, lack of consensus, institutional inertia, and public backlash against authoritarianism.

- The episode remains a pivotal chapter in India’s constitutional history, shaping ongoing debates about governance, executive power, and the future of Indian democracy.