Why Taiwan is racing to harden its air defenses

Taiwan is moving to expand its air defenses and raise military spending in response to a fast intensifying threat from China. The focus is clear, keep the skies above the island safe long enough to protect daily life and the manufacturing base that powers the global digital economy. Nowhere is that more crucial than Hsinchu Science Park, the dense cluster of labs and fabs that includes the headquarters and flagship plants of TSMC, the world’s largest contract chipmaker. A researcher advising Taiwan’s science authorities has warned that a single precision strike on Hsinchu could cut global GDP by 6 to 10 percent and make new iPhones scarce for up to three years, a stark reminder of how concentrated modern chipmaking has become.

- Why Taiwan is racing to harden its air defenses

- What Taiwan’s T-Dome aims to do

- Iron Dome comparisons, and why Taiwan’s challenge is different

- The silicon shield, and its limits

- How Beijing and Washington are responding

- Protecting Hsinchu and other chip hubs

- Costs, timelines, and the politics of getting it done

- Key Points

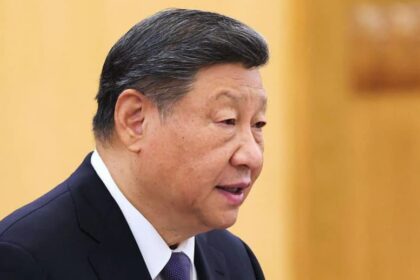

China says it seeks unification and has not ruled out force. U.S. intelligence assessments have suggested Beijing could have the capability to mount a major operation against Taiwan by 2027, even if capability does not equal intent. Any conflict or prolonged instability would ripple across the semiconductor supply chain, touching smartphones, data centers, cars, and military systems worldwide.

Washington and its partners are investing to diversify chip manufacturing, yet building a full ecosystem of suppliers, tooling, packaging, and talent outside Taiwan is a generational project. Even with new fabs underway in the United States, Europe, Japan, and elsewhere, experts estimate it could take at least two decades before the United States can produce the full spectrum of advanced chips without heavy reliance on Taiwan and China.

Taiwan calls its central place in chipmaking a silicon shield, the idea that the world’s reliance on its fabs deters war. Policymakers in Taipei increasingly caution that the shield may not be enough if China decides to disrupt or destroy, rather than seize, key facilities. That is why the government is moving to raise defense spending to 5 percent of GDP and accelerate a new air defense plan modeled in part on Israel’s experience.

What Taiwan’s T-Dome aims to do

President Lai Ching-te has unveiled plans for an all-domain air defense network known as T-Dome, a nationwide umbrella designed to track, classify, and intercept drones, rockets, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and potentially hypersonic weapons. The concept pairs a special defense budget with upgrades across sensors, command systems, and interceptors. The near term target is to lift defense spending beyond 3 percent of GDP next year and toward 5 percent by 2030, while kick-starting integration of domestic and foreign systems with smart software and automation for faster decision making.

In his National Day address, President Lai framed the goal in terms of resilience for society, not just the military.

We will accelerate our building of the T-Dome, establish a rigorous air defence system in Taiwan with multi-layered defence, high-level detection, and effective interception, and weave a safety net for Taiwan to protect the lives and property of citizens.

How it would work

T-Dome is conceived as a layered network. Taiwan already fields U.S.-made Patriot batteries and indigenous Sky Bow interceptors, and it recently presented a new system, Chiang-Kong, designed to reach higher altitudes and engage mid-level ballistic threats. T-Dome would connect these and other assets into a unified battle management picture that fuses radar, infrared sensors, electronic warfare data, and civil aviation feeds. The aim is to cue the right interceptor to the right target at the right moment, while preserving scarce missiles for the most dangerous threats.

Planners also want more mobility and survivability. A distributed architecture with mobile launchers, passive sensors, decoys, and hardened shelters increases the chance of riding out a first wave. The plan includes counter drone defenses around air bases, ports, and industrial zones, along with point defenses for critical electrical and water infrastructure that keep fabs running during a crisis.

What it must stop

The threat set is complex. China’s arsenal ranges from small quadcopters to cruise missiles that fly low and maneuver, to short and medium range ballistic missiles that descend at high speeds. Analysts also point to systems like the DF-17, which carries a maneuvering glide vehicle, and anti-ship missiles like the DF-26 that could target naval reinforcements. A workable T-Dome must discriminate among decoys and real warheads, defeat swarming drones, and handle saturation attacks designed to exhaust interceptors. That requires sensors with exceptional range and fidelity, fast networking, well-stocked magazines, and an industrial base that can replenish interceptors quickly.

Managing the cost of defense is central. An attacker can try to overwhelm defenses by launching more missiles than can be intercepted economically. Taiwan’s answer is multi-layered engagement, including lower cost interceptors and electronic warfare where possible, reserving high end missiles for the most dangerous tracks.

Iron Dome comparisons, and why Taiwan’s challenge is different

Comparisons to Israel’s Iron Dome are useful yet incomplete. Iron Dome is highly effective against short range rockets and some cruise threats, protecting civilian areas and critical sites. Taiwan faces a larger set of challenges. Ballistic missiles arrive much faster and from greater distances. China’s inventory is vast, and a campaign would likely combine ballistic and cruise missiles with drones and cyberattacks in quick succession. Geography also differs. Taiwan is an island in a tight air and sea theater, with potential threats approaching from multiple bearings over water.

These differences do not make the model irrelevant. Israel’s experience shows how layered architectures, high fidelity tracking, and rigorous command and control can keep a modern society functioning under sustained attack. Taiwan’s T-Dome would apply those lessons to a different mix of targets, pairing long range sensors and interceptors with point defenses around air bases, ports, government centers, and chip hubs. The success of such a system depends on operational discipline and the ability to move, rearm, and repair faster than an adversary can adapt.

The silicon shield, and its limits

Taiwan’s chip sector is the spine of global electronics. The island produces the majority of the world’s semiconductors and the great majority of the most advanced processor nodes used in premium smartphones, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. TSMC’s fabs in Hsinchu, Taichung, and Tainan anchor a supply chain that includes equipment vendors, specialty chemical plants, advanced packaging lines, and thousands of skilled engineers. A successful strike on any of these hubs would radiate through global markets.

Former Taiwanese leaders have emphasized that semiconductor strength supports both the economy and national defense by deepening partnerships and making Taiwan harder to isolate. Yet leaders across parties now caution that reliance on the silicon shield alone is risky. Deterrence only holds if all sides believe fabs will survive a crisis in working condition. If destruction becomes the goal, global costs may not stop aggression. For that reason, hardening chip zones, dispersing key processes, and expanding air defense are priorities.

Efforts to diversify the map of advanced manufacturing are underway. TSMC is moving to ramp production at new plants in Arizona, and new projects in Japan and Europe aim to add capacity. Even so, replicating Taiwan’s dense ecosystem of suppliers, tooling expertise, and packaging will take time. Many analysts estimate that a full shift away from reliance on Taiwan and China for leading edge chips could take at least 20 years. China, for its part, is investing heavily to reduce dependence on foreign chip technology, designing AI processors to replace imported parts restricted by export controls. The race to localize supply reduces vulnerabilities over time, yet the near term reality is that Taiwan remains central to advanced chips.

How Beijing and Washington are responding

Beijing has rejected President Lai’s defense agenda and his calls for peace through strength. China labels him a separatist and has paired rhetoric with military pressure around the island. After major speeches from Taipei in recent years, Chinese forces have flown military aircraft across the Taiwan Strait’s median line and staged exercises around the island, moves Taiwan’s military tracks closely.

At a press briefing in Beijing, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Guo Jiakun argued that any push for independence risks war.

Seeking independence by force would only drag Taiwan into conflict.

U.S. officials have publicly welcomed Taiwan’s effort to build credible defenses and cautioned against escalation. One senior official said Washington does not view public addresses as a justification for military coercion.

We do not think routine speeches should be used as a pretext for taking any sort of coercive or military action.

For Taiwan, messages from both capitals underscore the need to deter at the lowest possible cost while keeping society stable. The government has created a Whole-of-Society Defense Resilience Committee to improve coordination between agencies and the private sector so essential services, from electricity and water to emergency medical care, continue even during a crisis.

Protecting Hsinchu and other chip hubs

Hsinchu Science Park is often called Taiwan’s Silicon Valley for good reason. It concentrates wafer fabrication, design houses, advanced packaging, and research institutes within a short drive. Taichung and Tainan host additional mega-fabs. A defense plan that ignores these clusters would miss the core of Taiwan’s economic security. T-Dome’s backers want tailored protection around these sites, including counter drone systems, short range point defenses against low-flying cruise missiles, and rapid repair teams trained to restore power, water, and data links.

Critical infrastructure is a priority. Fabs consume vast amounts of ultra pure water and steady power. Backup reservoirs, redundant substations, protected transmission corridors, and diversified road and port access are part of resilience. Civil defense measures also matter, such as shelters near plants, clear evacuation routes, and stockpiles of spare parts and chemicals. Training industry security teams to work seamlessly with local police, firefighters, and military units can shorten recovery times after a strike.

War rarely respects supply chains. Even without a direct strike, a blockade or prolonged military activity around the island would disrupt shipping schedules and insurance costs. Drone and missile incidents in other sea lanes in recent years have shown how attacks far from factories can ripple through freight rates and delivery times. A robust air and missile defense buys time not only for the military, it helps keep commercial arteries open long enough for diplomacy to work.

Costs, timelines, and the politics of getting it done

Building T-Dome is expensive. Interceptors, radars, mobile launchers, and hardened shelters cost billions, and stockpiles must be deep enough to outlast a prolonged crisis. President Lai says the government will propose a special defense budget and push annual spending higher, with next year surpassing 3 percent of GDP and a longer term goal of 5 percent by 2030. That trajectory signals intent to fund both procurement and domestic production lines that can replenish missiles during a conflict.

Politics will shape the pace. Taiwan’s legislature is divided, and debates over how to balance defense, social programs, and economic investment are intense. Some opposition voices warn that military buildups invite confrontation, while security advocates argue that credible defenses reduce the risk of miscalculation. Industry will also have to adapt. Factories may need to adjust layouts to accommodate blast protection, redundancy, and rapid shutdown and restart procedures. Insurers and global customers will press for clear continuity plans.

Operational questions remain. Taiwan’s existing air defenses are robust but finite, and China’s missile inventory is large. T-Dome’s effectiveness will depend on how quickly Taiwan can add interceptors, expand training and exercises, and master distributed operations that keep units moving and concealed. Planners are also developing longer range missiles that can hold Chinese launch sites and logistics at risk, a deterrent that must be carefully calibrated to avoid unwanted escalation. The ultimate aim is straightforward, survive a first strike, keep the government and economy functioning, and hold the line long enough for help to arrive.

Key Points

- Taiwan is accelerating a new all-domain air defense network, T-Dome, to counter drones, rockets, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and potential hypersonic threats.

- President Lai targets defense outlays above 3 percent of GDP next year and aims for 5 percent by 2030, supported by a special defense budget.

- Hsinchu Science Park, home to TSMC and hundreds of tech firms, is seen as a prime target; a direct hit could cut global GDP by 6 to 10 percent and disrupt iPhone production for years.

- T-Dome will integrate Patriot and Sky Bow systems with a new Chiang-Kong interceptor and a unified command network to prioritize targets and preserve missiles.

- Comparisons to Iron Dome are directionally useful, but Taiwan faces a larger, faster, and more diverse missile threat that demands deeper magazines and greater mobility.

- The silicon shield, Taiwan’s central role in global chipmaking, helps deter conflict but is not a guarantee if an adversary chooses to disable rather than seize fabs.

- Efforts to reshore chipmaking are growing, yet experts estimate a full move away from reliance on Taiwan and China will take at least 20 years.

- Beijing criticized Lai’s plan, warning against independence by force, while a U.S. official cautioned against using speeches as a pretext for coercion.

- Protecting chip hubs requires counter drone defenses, hardened utilities, and close civil-military coordination to restore power, water, and data quickly after a strike.

- The strategy’s core purpose is to keep society functioning during a crisis and buy time for diplomacy and allied support.