A New Hero List Reopens Old Wounds

Around 100 activists gathered in central Jakarta near the presidential palace to demand that the government cancel a plan to grant the late president Suharto the title of national hero. The Social Affairs Ministry and the Culture Ministry have advanced a slate of 49 nominees for 2025, which includes Indonesia’s second president. The list now sits with President Prabowo Subianto, who will decide whom to recognize on 10 November, the date Indonesia marks Heroes Day. The nomination has reignited debate about Suharto’s legacy and whether the nation is ready to inscribe his name among figures publicly celebrated for virtue and service.

Protesters framed the plan as an attempt to rewrite history. Placards read “Stop the Whitewashing of the General of Butchery” and “Thousands Died But The Country Chose to Forget.” Among the groups on the streets were Amnesty International Indonesia and the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence, known as KontraS. Their message was direct. The state should not honor a leader whose decades in power were marked by reports of severe abuses and vast corruption networks. Organizers said the push to place Suharto on the roll of heroes sends the wrong signal to victims, survivors and students who learn from official narratives.

Suharto ruled for 32 years under the New Order, a period defined by restrictions on political opposition, a powerful security apparatus, and a tightly managed press. He resigned in May 1998 during the Asian financial crisis after weeks of student led demonstrations and deadly riots in Jakarta. For many Indonesians the wounds of that era still feel open. Civil society groups argue that bestowing the highest honor on the general who rose to prominence after 1965 risks normalizing mass violence and burying demands for truth and accountability.

How Indonesia Picks National Heroes

The national hero title, Pahlawan Nasional Indonesia, is the country’s highest formal recognition for extraordinary service to the state and its people. Most recipients are honored posthumously. Nominations are typically initiated at the local level by citizens or regional leaders, then processed by the Social Affairs Ministry’s research and review team for titles. The Council for Titles, Decorations, and Honors evaluates the recommendations. The president has the authority to approve the final list, which is announced each year on Heroes Day.

Culture Minister Fadli Zon, who chairs the council that submits the shortlist to the president, said the process takes public input seriously and that all nominees meet formal requirements after multiple rounds of academic and community review. Officials noted that 24 of the 49 nominees are on a priority list, and that some names have been proposed repeatedly in previous years. The ministries say the government assesses background, contributions, and historical records before a decision is made.

What criteria apply

Indonesian law sets an ethical bar for anyone to be named a national hero. Beyond documented contributions, the honoree must be seen as a moral exemplar who embodies social justice and stands with the public. Rights advocates argue Suharto fails that test. Usman Hamid, executive director of Amnesty International Indonesia, told reporters that the legal standard cannot be squared with Suharto’s record.

“The law states that a hero must possess moral exemplarity, must have moral integrity, and must embody the qualities of social justice, humanitarian justice, and being on the people’s side. Now, if those values are applied to Suharto being given the title of national hero, those values are precisely contradicted.”

State Secretary Prasetyo Hadi has said the president is reviewing the shortlist and holds the sole authority to decide the final lineup that will be announced on 10 November.

Why Suharto Divides Indonesia

The sharpest arguments against honoring Suharto focus on the bloody transition that brought him to power. After a failed coup in late 1965 blamed on communists, the army and allied militias detained and killed hundreds of thousands of people. Historians and rights groups commonly cite a death toll of at least 500,000, with some estimates approaching one million. Suharto was a key military commander during that period and soon consolidated control of the state.

During the New Order era, the government curtailed dissent, banned the communist party, and sent security forces to quell unrest. Toward the end of his rule, students led large demonstrations demanding change. In 1998, troops and paramilitaries were accused of violent crackdowns, with families still seeking answers about abductions and deaths. Critics say a hero designation would minimize those events and weaken efforts to teach the darker parts of the past.

Supporters tend to highlight stability and growth in the first two decades of Suharto’s administration. Inflation was tamed after the 1960s, infrastructure expanded, and the country saw improvements in basic services. To critics, those gains came at the price of civil liberties, independent institutions, and the nurturing of patronage networks that enabled corruption to flourish.

A public letter signed by hundreds of activists, academics, and civic leaders urged President Prabowo not to proceed.

“The awarding of the title of national hero to Suharto is not only a betrayal of the victims and democratic values, but also a betrayal of reform and a dangerous distortion of history for the younger generation.”

For many Indonesians, the core issue is the message the state sends by elevating a former ruler whose tenure coincided with mass violence and systemic rights violations. Survivors and their families say that honoring Suharto risks deepening a culture of impunity and undermines the promise of reform that followed 1998.

Voices From the Protest

On the streets, the statements were blunt. Virdinda La Ode Achmad, a researcher with the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence, questioned the push to elevate Suharto while memories of repression remain raw.

“If he deserves to be a hero, why did he step down and why did the New Order have to be overthrown?”

Maria Catarina Sumarsih, whose son was killed during a 1998 protest, has been a central figure in weekly Thursday vigils that call for justice for the disappeared. She said any move to lionize Suharto would add to the pain of families who still wait for truth and accountability.

“National unity should be built on honesty, not lies.”

Other survivors and families described lasting trauma from imprisonment, disappearances, and intimidation during the New Order years. Their concerns reach beyond symbols. They fear that when the state elevates a controversial figure as a model of service, it becomes harder to secure acknowledgment of past wrongs and to teach future generations what went wrong.

The Government Position and the Case for Recognition

Culture Minister Fadli Zon, who helps oversee the vetting process, defended the handling of nominations and stressed that the council weighs public views and academic research before making recommendations to the president.

“The process includes public input and all candidates meet the requirements.”

Officials and supporters cite Suharto’s earlier military record as part of the case for recognition, including his leadership role in the March 1, 1949 General Offensive during the Dutch military campaign and his involvement in the campaign that led to the integration of West Irian with Indonesia in the 1960s. Within this frame, Suharto is presented as a soldier who helped defend the republic and as a leader who guided economic expansion.

Some political figures have argued that conferring the honor could advance national reconciliation. They say acknowledging contributions while recognizing mistakes would allow the nation to move forward. Opponents counter that reconciliation requires an honest accounting and concrete steps toward justice, not state accolades for the most powerful figure of the era.

Prabowo’s Decision and the Politics Around It

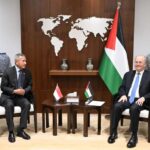

President Prabowo Subianto was elected in 2024 after a campaign that emphasized security and economic growth. He is Suharto’s former son in law and has spoken approvingly of the New Order. In office he has relied on senior military figures to implement parts of his agenda. The State Secretary, Prasetyo Hadi, said the president is reviewing the shortlist of national heroes and will finalize the list by 10 November.

Hundreds of activists, academics, and civil society organizations have appealed directly to the palace to reject Suharto’s nomination. The letter that reached the president also catalogued abuses under the New Order and warned that honoring the former leader would harm democratic consolidation.

Former attorney general Marzuki Darusman, who signed the letter, framed the risk in stark terms.

“If Suharto is awarded national hero status, it will be a monumental neglect of and insensitivity toward the human rights violations.”

The debate has unfolded alongside periodic public protests over living costs and political privilege. Analysts say the decision on Suharto will shape perceptions of how the new administration balances calls for stability with demands for accountability.

History, Memory, and the Classroom

Titles and monuments help determine which stories future students learn and celebrate. A state declaration of heroism can influence textbooks, films, and public commemorations. That is why many teachers, historians, and activists warn against normalizing a narrative that sidelines victims and treats mass violence as an acceptable price for order.

A coalition of domestic and international civic groups said honoring Suharto would damage Indonesia’s standing on rights and would be a blow to survivors who continue to seek redress.

“Granting the title of national hero to a perpetrator of crimes against humanity would be a betrayal for victims and survivors of past human rights violations, many of whom have yet to receive recognition, justice, or reparations.”

Supporters of the nomination sometimes argue that a more balanced portrayal is needed and that modern Indonesia should recognize both achievements and failures of past leaders. Critics reply that balance must begin with truth and that, before honors are bestowed, the state should complete credible investigations, acknowledge abuses, and commit to non recurrence.

Other Names on This Year’s List

The 2025 nominees include figures who symbolize very different threads in Indonesian history. Former president Abdurrahman Wahid, often known as Gus Dur, is among them. So is Marsinah, a factory worker and labor organizer who was kidnapped and murdered in 1993. Their stories offer a counterpoint to the New Order narrative and reflect broader debates on pluralism, labor rights, and the rule of law.

The Council for Titles, Decorations, and Honors says the list draws on submissions from across the country and that it continues to seek balanced representation. Officials stated that of the 49 names advanced this year, nine were proposed previously and 40 are new submissions. A portion of the list is labeled priority based on the strength of documentation and national contribution.

Who the president ultimately recognizes will signal what values the state chooses to elevate at this moment. Honoring Marsinah would underscore commitment to the dignity and safety of workers. Honoring Gus Dur would emphasize inclusion and respect for civil society. Honoring Suharto would set a very different tone.

What to Know

- About 100 activists rallied in Jakarta to oppose plans to name Suharto a national hero.

- The Social Affairs and Culture ministries nominated 49 candidates to President Prabowo for recognition on 10 November.

- Rights groups and survivors argue Suharto’s record of abuses and corruption makes him unfit for the honor.

- Culture Minister Fadli Zon says nominations include public input and that all candidates meet requirements after review.

- Supporters cite Suharto’s military service and early economic management as reasons for recognition.

- Other nominees include former president Abdurrahman Wahid and labor activist Marsinah.

- State Secretary Prasetyo Hadi says the president has the final say and will decide by Heroes Day.

- The decision is a test of how the government balances stability, historical truth, and justice for victims.