Record gap lays bare the rise of low paid part time work

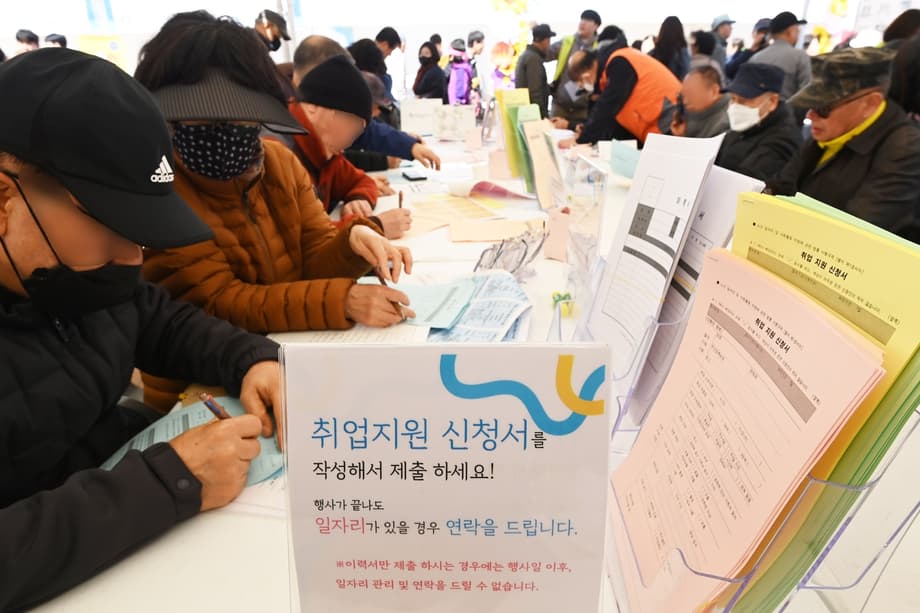

South Korea’s wage divide between regular and nonregular employees has reached a record high. Between June and August, nonregular workers earned an average of 2.09 million won per month, while regular employees earned 3.90 million won. The 1.81 million won shortfall is the largest gap since comparable data began in 2004, according to the Ministry of Data and Statistics. The figures arrive as the country grows older and as more seniors take part time jobs in care and social services.

- Record gap lays bare the rise of low paid part time work

- Why more seniors are taking low paid roles

- Care and welfare jobs lead growth yet pay trails

- A labor market tilted toward older and female workers

- What the headline gap hides

- Economic stakes for a super aged society

- What could close the gap

- What to Know

In Korea, nonregular workers include part time, temporary, and fixed term employees, as well as many staff on contracts without the benefits and security common in large corporate payrolls. The headline gap reflects differences in both hourly pay and hours worked. When part time roles are excluded, the average monthly wage for nonregular staff rises to 3.04 million won. That narrows the difference with regular employees to 859,000 won, underscoring the outsized effect of shorter hours and lower hourly pay in a growing segment of the labor market.

The scale of nonregular work is large. As of August, 8.57 million people held nonregular jobs, up 110,000 from a year earlier, equal to 38.2 percent of all wage workers. The composition is changing as the population ages. For the first time, the number of nonregular workers aged 60 and older exceeded 3 million, after a year on year increase of 233,000. People aged 60 and above now account for 35.5 percent of the nonregular workforce, the highest share on record. Workers aged 70 and over, at 1.21 million, now outnumber those in their 40s. Women hold 57.4 percent of nonregular positions, another record.

Why more seniors are taking low paid roles

Many retired or soon to retire Koreans are returning to work to supplement modest pensions, maintain social ties, and manage living costs. In larger firms, a mandatory retirement age of 60 is widely used. Many workers see their pay reduced in their late fifties under wage peak arrangements, then leave their primary employer and reenter the labor market in lower paid, less secure roles. Publicly funded employment programs for older residents have expanded opportunities, particularly in community care, but the typical positions are part time and pay relatively little.

Retirement rules and the wage peak system

Under the wage peak system, companies reduce salaries for older employees while keeping duties largely intact. The savings are intended to help finance junior hires, yet the approach can leave older staff with fewer years to build savings before retirement. Human Rights Watch has described the practice as age based discrimination that pushes older workers into precarious work. Bridget Sleap, a researcher on older people’s rights at the group, said the current rules undercut fair treatment.

These measures were designed to protect workers but they do the opposite. They deny older workers the opportunity to continue working in their main jobs, pay them less, and push them into lower paid, precarious work, all because of their age.

As debate grows about how long people should work, some political leaders have floated raising the mandatory retirement age to 65 to better align with pension eligibility. Labor lawyer Kim Ki duk has warned that a narrow focus on the age threshold would miss the core problem, which is how pay is set inside firms.

Simply raising the retirement age to 65 would give companies more years to apply discriminatory wage cuts under the current system.

The central choice is clear. Keep more seniors in their main jobs for longer with fair pay, or accept a growing pool of lower paid part time work that strains household budgets.

Care and welfare jobs lead growth yet pay trails

The health and social welfare sector now accounts for the largest share of nonregular employment at 20.5 percent, or roughly 1.76 million workers. The sector added about 210,000 nonregular jobs over the past year, the biggest increase of any industry. The growth reflects mounting demand for elder care and health services in a super aged society. Many of these jobs are meaningful, close to home, and attractive to seniors who want flexible hours. They are also among the lowest paid positions in the economy and are frequently part time. That mix is a major reason nonregular wages have stagnated while headcounts rise.

Why wages in care remain low

Care providers often operate on tight margins. Public fee schedules can limit revenue growth, and many organizations rely on short shifts to match client needs. Employers report difficulty filling long, physically taxing roles, so schedules are split and hours compressed. Training requirements and emotional demands are high, yet pay levels lag jobs in manufacturing or business services. High turnover adds costs, which further squeezes wages. Without better funding, standards, and career ladders, care work will keep attracting older workers while keeping average pay low.

A labor market tilted toward older and female workers

Women now make up a record share of nonregular staff. Many value flexible schedules that fit with family and caregiving responsibilities, and some face barriers moving into regular roles after career breaks. The aging of the workforce is reshaping the profile of nonregular employees. For the first time, workers aged 70 and above outnumber those in their 40s in this group. Those in their 30s have also grown as a share, now about 13.3 percent, while participation has drifted down among people under 30 as well as in their 40s and 50s. About two thirds of nonregular workers say they accepted their arrangements by choice, citing flexibility or satisfaction with conditions. A sizeable 32.2 percent say their status is not voluntary, most often because of urgent income needs or a lack of roles that match their skills.

What the headline gap hides

The wage gap is measured on monthly pay, which reflects both the hourly rate and the number of hours worked. The rapid expansion of part time jobs, especially in care, has a powerful effect on the averages. When part time roles are stripped out, the nonregular average jumps to 3.04 million won. Even then, a gap remains. That difference also reflects benefits and security that are not captured in pure wage data. Regular workers are more likely to receive bonuses, paid leave, stronger severance, and employer pension contributions. Nonregular workers often lack these protections and may face gaps in hours from week to week.

Regional and sectoral contrasts

The fastest hiring is concentrated in health and social services, often backed by public programs for older residents. By contrast, nonregular employment has fallen in hospitality, construction, and retail, sectors that feel the weight of weak domestic demand. Larger corporations tend to keep a smaller share of nonregular staff and offer higher pay. Smaller employers, especially in services, rely more on contracts and part time schedules. The result is a dual labor market where company size and industry shape pay and stability as much as individual performance.

Economic stakes for a super aged society

Korea is aging at a speed matched by few countries. Fertility is far below the level needed to keep the population steady, and life expectancy is high. Global research shows that as societies age, the number of working age people per senior declines sharply. In advanced economies the support ratio is on track to approach two working age adults per senior by 2050. That means each worker must carry more of the costs of retirement and care. Seniors already account for a rising share of consumption, and public pension systems face growing pressure. Without faster productivity growth or more hours worked, economic growth per person is likely to slow.

Why productivity and skills matter

A tight labor market makes it essential to keep older workers engaged in roles that match their abilities. That requires training and job redesign. Digital tools can simplify routine tasks. Assistive equipment can reduce physical strain in care and manufacturing. Flexible schedules and phased retirement let experienced workers contribute while managing health or family needs. Raising productivity in sectors that are hiring large numbers of seniors, especially care, is central to protecting living standards and limiting the wage gap.

What could close the gap

The drivers of the record wage gap are clear. A larger share of older workers is entering nonregular, part time roles in care and social services. Pay in those roles is low. Retirement rules and wage practices push many out of their main jobs in their late fifties. A stronger policy response will need to move on several fronts at once.

- Raise pay and standards in care by updating fee schedules, setting minimum staffing ratios, and funding training tied to clear career pathways.

- Promote equal pay for work of equal value across employment status so that nonregular workers doing the same tasks receive comparable base pay and benefits.

- Shift from seniority based pay toward systems that reflect job value and performance, which can reduce the need for wage peak cuts tied to age alone.

- Offer targeted upskilling and certification for mid career and older workers, especially in fast growing services and digital roles.

- Create flexible retirement options, such as phased schedules and partial pensions, to support steady income without forcing abrupt exits at 60.

- Review public senior employment programs to ensure they complement, rather than crowd out, private sector jobs and that they lead to better quality roles over time.

- Expand portable benefits for part time and contract workers, including access to paid leave, severance, and pensions, to reduce insecurity not captured in headline wages.

- Encourage technology adoption and process improvements in care to boost productivity while protecting quality and safety.

- Address barriers that limit women from moving into regular roles after career breaks, including affordable childcare and fair reentry pathways.

None of these steps alone will erase the gap quickly. Together they can lift the floor under pay, widen choices for older residents who want to work, and make the labor market less divided. The record figures highlight a simple point. Korea has more people working in care and support roles that society needs. Paying those workers better and designing fairer wage systems would help align a changing workforce with a changing economy.

What to Know

- Average monthly pay for nonregular workers was 2.09 million won between June and August, compared with 3.90 million won for regular staff. The gap of 1.81 million won is a record.

- Excluding part time roles, the nonregular average rises to 3.04 million won, cutting the gap to 859,000 won.

- Nonregular workers reached 8.57 million in August, or 38.2 percent of wage workers. The number rose by about 110,000 from a year earlier.

- For the first time, more than 3 million nonregular workers are aged 60 and older, representing 35.5 percent of the group.

- Jobs in health and social welfare made up 20.5 percent of nonregular roles, or about 1.76 million workers, after a year on year increase of roughly 210,000.

- Women hold 57.4 percent of nonregular positions. About two thirds of nonregular workers report choosing their status, while 32.2 percent say it is not voluntary.

- Human Rights Watch has criticized wage peak practices, and labor experts urge wage reform that ties pay to job value rather than age.