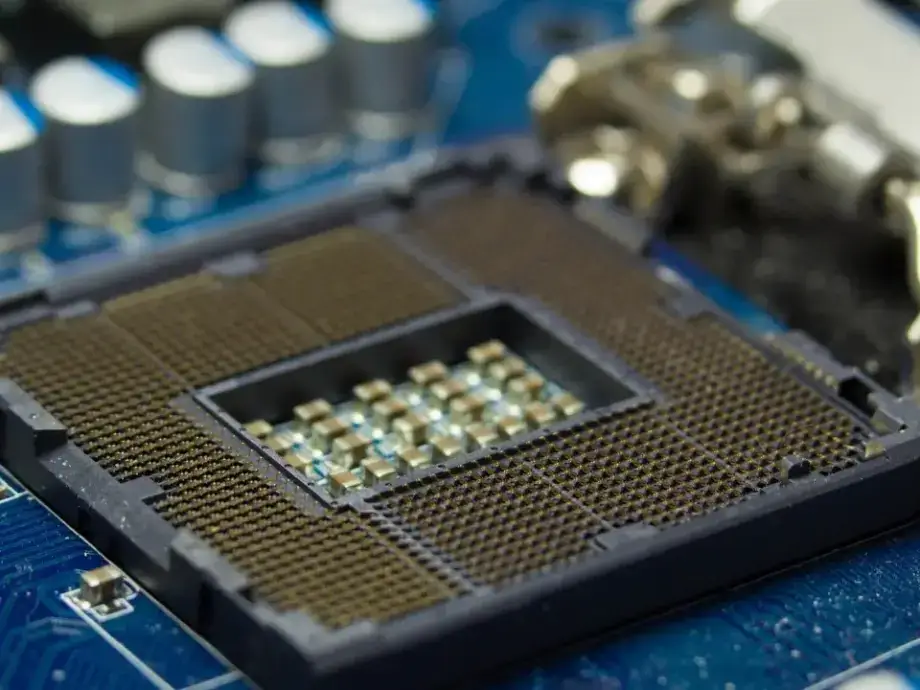

US Plans New AI Chip Export Restrictions: What’s Changing and Why?

The United States is preparing to introduce new restrictions on the export of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) chips to Malaysia and Thailand, a move designed to prevent these high-tech components from being diverted to China. This policy shift, led by the Trump administration, marks a significant evolution in Washington’s ongoing efforts to control the flow of cutting-edge technology and maintain its lead in the global AI race.

- US Plans New AI Chip Export Restrictions: What’s Changing and Why?

- Background: The US-China Tech Rivalry and the Role of AI Chips

- Why Malaysia and Thailand? The Southeast Asian Semiconductor Surge

- How Are Chips Diverted? The Smuggling and Circumvention Challenge

- From Biden’s AI Diffusion Rule to Trump’s Targeted Controls: What’s Different?

- Industry and Regional Reactions: Balancing Security and Economic Growth

- Implications for the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain

- What’s Next? Enforcement, Exemptions, and the Future of AI Chip Controls

- Broader Geopolitical and Economic Impacts

- In Summary

At the heart of the new draft rule from the US Commerce Department is a concern that, despite direct bans on sales of Nvidia’s most advanced AI processors to China, these chips are still reaching Chinese companies through third-party countries. Malaysia and Thailand, both major players in the global semiconductor supply chain, have seen a surge in chip shipments and investments in data centers, raising red flags in Washington about potential smuggling or diversion.

The proposed regulation is not yet finalized and could still change. However, it signals a clear intent to tighten controls on the export of AI chips to Southeast Asia, while also rescinding the broader, more controversial “AI Diffusion Rule” introduced at the end of the Biden administration. This new approach is expected to have far-reaching implications for the global semiconductor industry, US-China relations, and the economic strategies of Southeast Asian nations.

Background: The US-China Tech Rivalry and the Role of AI Chips

AI chips, such as Nvidia’s H100 and A100 graphics processing units (GPUs), are essential for training and running large-scale artificial intelligence models. These chips provide the massive computational power required for breakthroughs in machine learning, natural language processing, and other advanced AI applications. As a result, they are at the center of a fierce technological competition between the US and China.

Since 2022, the US has imposed a series of escalating export controls to restrict China’s access to advanced semiconductors and related technologies. The rationale is twofold: to maintain America’s technological edge in AI and to prevent China from using US-origin technology for military or surveillance purposes. These controls have included direct bans on the sale of high-end AI chips to China and a growing list of countries considered at risk of diverting technology to Beijing.

However, as the global supply chain for semiconductors is highly complex and interconnected, US officials have become increasingly concerned that chips exported to third countries—especially in Southeast Asia—could ultimately end up in Chinese hands. This has led to a focus on Malaysia and Thailand, both of which have become critical nodes in the global semiconductor ecosystem.

Why Malaysia and Thailand? The Southeast Asian Semiconductor Surge

Malaysia and Thailand have emerged as major hubs for semiconductor manufacturing, assembly, testing, and packaging. Malaysia, in particular, is the world’s fourth-largest semiconductor exporter, with exports reaching nearly $37 billion in 2024. A significant portion of these exports—over a third—are destined for China and Hong Kong. Thailand, while smaller in scale, exported over $800 million in integrated circuits to China in 2023.

This growth is driven by several factors:

- “China Plus One” Strategy: As US-China tensions have escalated, global tech companies have sought to diversify their supply chains, investing heavily in Southeast Asia to reduce reliance on China.

- Foreign Direct Investment: Major US firms like Nvidia, Oracle, Intel, and GlobalFoundries have ramped up operations in Malaysia and Thailand, attracted by skilled labor, established infrastructure, and favorable trade policies.

- Data Center Boom: Companies such as Oracle, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Amazon Web Services are investing billions in new data centers in Malaysia and Thailand, further increasing demand for advanced AI chips.

While this has brought economic benefits to the region, it has also created new challenges for US export control enforcement. The risk is that chips shipped to Malaysia or Thailand could be re-exported to China, or that Chinese companies could gain remote access to AI computing power hosted in Southeast Asian data centers.

How Are Chips Diverted? The Smuggling and Circumvention Challenge

Despite direct bans, Chinese companies have found creative ways to access restricted US technology. One method, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, involves physically transporting hard drives loaded with AI training data to Malaysia, where Chinese engineers rent servers equipped with Nvidia chips. They train their AI models in Malaysian data centers and then bring the results back to China. This approach allows Chinese firms to bypass US restrictions on direct chip exports by leveraging Southeast Asia’s growing data infrastructure.

There have also been legal cases highlighting the risks of diversion. In Singapore, prosecutors have charged individuals with defrauding customers about the ultimate destination of AI servers originally shipped to Malaysia, which may have contained advanced Nvidia chips. While Nvidia is not implicated in wrongdoing, the case underscores the difficulty of tracking the end-use and final destination of high-value technology products.

Malaysian officials, under US pressure, have pledged to tighten oversight of semiconductor shipments. Trade Minister Zafrul Aziz confirmed that the US has asked Malaysia to ensure that servers with Nvidia chips end up in designated data centers and are not redirected elsewhere. The scrutiny is part of a broader US effort to limit China’s access to advanced technology.

From Biden’s AI Diffusion Rule to Trump’s Targeted Controls: What’s Different?

The new draft rule comes as the Trump administration moves to rescind the so-called “AI Diffusion Rule” introduced at the end of the Biden administration. That rule divided countries into three tiers based on their relationship with the US and set quotas for the number of advanced AI chips that could be exported to each tier. Trusted allies like the UK and South Korea faced few restrictions, while countries like China and Russia were effectively barred from access. Most of the world, including Malaysia and Thailand, fell into a middle tier with limited quotas and strict licensing requirements.

The AI Diffusion Rule faced criticism from US allies and tech companies, including Nvidia, who argued that it created unnecessary red tape, stifled innovation, and risked alienating friendly nations. The Trump administration’s new approach is to replace the blanket, tiered system with more targeted, country-specific controls. The focus is now on preventing diversion through key intermediaries—starting with Malaysia and Thailand—while maintaining flexibility to adjust the list of controlled countries as needed.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick explained the new vision to lawmakers:

“The US will allow our allies to buy AI chips, provided they’re run by an approved American data center operator, and the cloud that touches that data center is an approved American operator.”

This approach aims to balance national security concerns with the need to support American innovation and maintain strong alliances.

Industry and Regional Reactions: Balancing Security and Economic Growth

The proposed restrictions have sparked debate among industry leaders, regional governments, and policy experts. Nvidia, the dominant maker of AI chips, has declined to comment directly on the new rules. However, CEO Jensen Huang has previously stated that there is “no evidence” of widespread AI chip diversion, while warning that overregulation could ultimately help China develop its own alternatives and erode US market leadership.

Malaysian and Thai officials have responded cautiously. Malaysia’s Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry has emphasized the need for clear and consistent policies to support the tech sector, while Thailand is awaiting further details on the curbs. Both countries are keen to maintain their status as attractive destinations for foreign investment, but are also under pressure to demonstrate compliance with US export controls.

Local industry players in Thailand, such as Siam AI Cloud and Ingram Micro, are stepping up compliance measures, including pre-auditing customer orders and verifying end-users to prevent chips from being re-exported to China. However, there is uncertainty about how the new rules will affect cloud service providers and data center operators, especially if Chinese companies seek to access AI computing power remotely.

Implications for the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain

The new US export controls are likely to have significant ripple effects across the global semiconductor industry. Southeast Asia’s rise as a semiconductor hub is both an opportunity and a risk. On one hand, the region stands to benefit from increased investment, job creation, and technological advancement as companies diversify away from China. On the other hand, tighter US controls could disrupt supply chains, increase compliance costs, and complicate cross-border R&D collaboration.

For China, the restrictions present both challenges and incentives. While direct access to US-made AI chips is increasingly difficult, Chinese firms are investing heavily in domestic alternatives and seeking creative ways to circumvent controls. The risk for the US is that overly restrictive policies could accelerate China’s push for self-sufficiency in semiconductors, potentially undermining America’s long-term technological advantage.

For investors and industry strategists, the shift highlights the importance of logistics, infrastructure, and compliance expertise. Companies involved in semiconductor testing, packaging, and logistics in Malaysia and Thailand—such as Unisem, Jotana, and MySETEC—are poised for growth as redistribution hubs. However, they must also navigate the risks of geopolitical volatility, changing regulations, and potential market saturation.

What’s Next? Enforcement, Exemptions, and the Future of AI Chip Controls

The draft rule includes several provisions to ease the transition for companies with significant operations in Malaysia and Thailand. For a few months after the rule is published, firms headquartered in the US and a select group of allied nations will be allowed to continue shipping AI chips to both countries without seeking a license. There will also be exemptions to prevent supply chain disruptions, recognizing that many semiconductor companies rely on Southeast Asian facilities for crucial manufacturing steps like packaging.

However, the new controls are not a comprehensive replacement for the previous system. Key questions remain about how the US will monitor the use of its chips in overseas data centers, especially in regions like the Middle East where security concerns are high. Officials have not ruled out extending the controls to additional countries if evidence of diversion emerges.

Enforcement will be a major challenge. The US is expected to increase “red flag” scrutiny of transactions, requiring companies to conduct due diligence and report suspicious activity. Southeast Asian governments may need to strengthen their own export control laws and compliance frameworks to avoid being blacklisted or losing access to US technology.

Broader Geopolitical and Economic Impacts

The tightening of US export controls on AI chips is part of a broader trend of technological decoupling between the US and China. As both countries vie for leadership in AI and other advanced technologies, the global supply chain is being reshaped. Southeast Asia finds itself at the crossroads of this competition, with opportunities for growth but also heightened risks.

For the US, the challenge is to maintain its technological edge while supporting allies and avoiding unintended consequences. For Southeast Asian countries, the priority is to balance economic development with compliance and security obligations. For China, the restrictions are both a barrier and a catalyst for domestic innovation.

As the rules evolve, all stakeholders will need to adapt. The winners will be those who can navigate the complex landscape of technology, trade, and geopolitics—leveraging new opportunities while managing the risks of a rapidly changing world.

In Summary

- The US is preparing new export restrictions on advanced AI chips to Malaysia and Thailand to prevent diversion to China.

- The move replaces the broader “AI Diffusion Rule” with more targeted, country-specific controls.

- Malaysia and Thailand have become key semiconductor hubs, attracting major investments but also raising concerns about chip smuggling.

- Chinese companies are using creative methods, such as remote data center access and physical data transfers, to circumvent US controls.

- The new rules include temporary exemptions and phased implementation to minimize supply chain disruptions.

- Industry leaders and regional governments are balancing compliance with the need to support economic growth and innovation.

- The global semiconductor supply chain is being reshaped, with Southeast Asia playing an increasingly important role.

- Enforcement and compliance will be critical as the US seeks to maintain its technological edge and prevent unauthorized technology transfers.

- The broader US-China tech rivalry continues to drive policy changes, investment strategies, and global economic realignment.