A moment of peace in the shadow of Okinawa

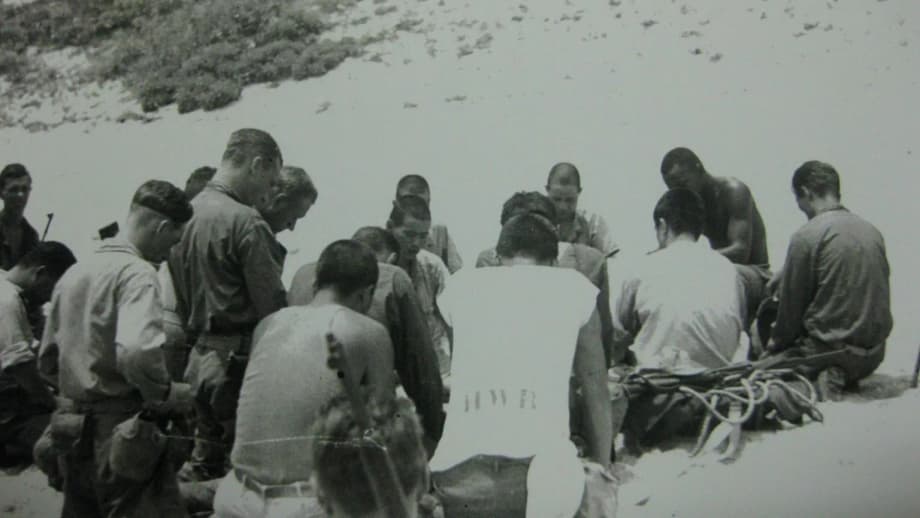

On a remote beach in the Kerama Islands west of Okinawa, United States Marines and Japanese soldiers briefly put down their weapons in late June 1945. They met face to face, shared food, and knelt together in prayer. The truce that took shape on Aka Island came during the last phase of the Battle of Okinawa, one of the Pacific War’s deadliest campaigns. It prevented further bloodshed on that island and left behind a single, haunting photograph of enemies side by side. For decades the story was barely known beyond those who lived it, but this year descendants, islanders, and researchers gathered on Aka to remember the day when war paused long enough for a picnic.

Scholars now argue that the episode deserves a place alongside the Christmas truces on the Western Front in 1914. The context was very different. On Okinawa, civilians had been told that capture meant torture or death, and American troops had been trained to expect fierce resistance. That a group of combatants chose to talk, eat and pray together in that climate of fear makes the Aka truce a rare window into choices made by individuals under intense pressure.

The battle around them was catastrophic. The Cornerstone of Peace memorial lists more than 240,000 dead in the Battle of Okinawa. More than half were Okinawan civilians. The Japanese army fortified caves and tunnels and ordered soldiers to fight to the end. Civilians were coerced into group suicides in some places, and many families acted out of terror. The small decision to halt fighting on Aka Island did not change the outcome of the war, yet it spared the island’s residents and garrison further destruction in the final weeks before Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945.

How the truce unfolded

In early June 1945, Marine Lieutenant Colonel George Clark was ordered to secure Aka, where a few hundred Japanese soldiers were still in the hills. Rather than storm the island, Clark assembled a small team of Marines and soldiers, and he brought Japanese prisoners who were willing to help. The Americans circled the shore in small craft from June 13, broadcasting surrender appeals with portable loudspeakers. Day after day nothing happened.

The impasse ended in a strange way. On June 19, Lieutenant David Osborn jumped into the water and swam ashore to leave flags and messages. Somewhere in the brush he encountered a Japanese soldier who did not harm him. Through intermediaries, the garrison commander, Major Yoshihiko Noda, said he would meet the Americans if one man came with them, Major Yutaka Umezawa. Umezawa had been wounded and captured at the start of the battle. His treatment in captivity had convinced him that more fighting on Aka was pointless, and he was willing to speak to his old comrade.

On June 26, Clark’s party returned to a quiet strip of sand called Utaha Beach with Umezawa carried on a stretcher. Japanese soldiers watched from the high ground. The two commanders stepped forward, saluted and set their weapons aside. Negotiations began. As the hours passed, Clark ordered food to be brought ashore. Soldiers who had faced each other at a distance now shared roast pork, canned rations and sweet potatoes. They talked across the sand like men who understood what another fight would cost. For a few hours, the front line felt like a picnic.

In his official report, Clark tried to convey what the scene felt like to a Marine officer in wartime.

It was the most amazing spectacle it has been my lot to behold.

Trust deepened in small gestures. Noda invited two Americans to his command post, offered hospitality, and even had his men dry their soaked shirts. The next day, Noda’s adjutant, Second Lieutenant Yoshiyuki Takeda, delivered the answer. The garrison could not surrender without permission from the emperor, a rule that had the force of sacred command. A tacit truce was acceptable. If the Americans refrained from attacking, they could move freely on the beaches to swim or collect shells. Clark then asked if the Japanese would join a short prayer to the Supreme Being of all faiths for international understanding and peace, led by a United States chaplain. They agreed. From that day to Japan’s surrender, there were no more deaths on Aka.

Who took the risks and why surrender was off the table

To understand why a truce was possible but surrender was not, consider the orders then in force. With organized resistance collapsing, Generals Mitsuru Ushijima and Isamu Cho told their men to fight to the end and to avoid the shame of capture. In that climate, opening talks with the enemy risked court martial, and even Japanese officers who favored an end to bloodshed had little authority to capitulate. American commanders, for their part, were expected to neutralize remaining garrisons. Negotiation in the open, on a beach within range of rifles, carried its own dangers. The Japanese prisoners who spoke over the loudspeakers also took risks, since cooperation could later be punished.

Trudy Johnson, Clark’s daughter, has long argued that the event stayed obscure because it did not fit official narratives. The Marines did not achieve a formal surrender. The Japanese officers negotiated without orders. For her father, a relationship with Major Umezawa proved crucial. Johnson recalled the long conversation that helped set the meeting in motion.

One night my Dad talked to him for hours trying to persuade him to help.

Scholars in Japan have added that for the former Imperial Army, unauthorized contacts with the enemy were a grave breach of discipline. Yet a small group on both sides judged that saving lives mattered more. The truce they shaped shows what individual agency can look like inside a rigid system.

The people behind the meeting

The Aka story was not a miracle. It moved forward because specific men took specific risks and then stood by their decisions in the days that followed.

Lt Col George Clark

Clark, a Marine reservist leading a small detachment, resisted the simple path of using overwhelming force on a tiny island. He never returned to Japan after the war. Late in life he heard rumors that Japanese officers who met him had been executed for treason. A Japanese journalist visited his home in 1987 and told him those men were alive and proud of what they had done. His daughter preserved his photographs and correspondence and kept telling the story of a commander who thought hard about the cost of each order.

He used to say, I think we as a team did the world some good.

Major Yoshihiko Noda and his officers

Noda led a garrison of roughly two hundred soldiers who had lived in the hills for months. He could not issue a formal surrender. He could, and did, make space for a ceasefire that held. As a gesture of courtesy during the talks he invited two Marines to his command post, offered tinned pineapple, and had their shirts dried. His adjutant, Second Lieutenant Yoshiyuki Takeda, delivered the decision that two realities could not be bridged that day, allegiance to the emperor and a wish to spare lives. The record also shows the dark side of garrison life at the time. Early in the battle, Noda’s men executed starving Korean laborers for theft. The truce does not erase that crime. It does, however, show how men in the same unit could choose restraint later when faced with a different choice.

David Osborn

Osborn’s impulsive swim to shore became the hinge in the story. In uniform he was an intelligence officer who helped coax a meeting into place. In later decades he served the United States as a career diplomat in Asia and went on to be ambassador to Burma in the 1970s. Friends and colleagues remembered his energy and love of sports, and residents in Rangoon called him the bicycle ambassador. His path from a wartime beach to years of patient public service is one thread that links the Aka truce to a later peace.

Life on Aka and the cost of the wider battle

Aka is a small island in the Kerama group, a short distance from Okinawa. When American forces reached the area in March 1945, civilians fled to ravines and caves. Many families believed capture meant torture or worse. Across Okinawa the Japanese military had drilled into civilians that surrender was shameful. That propaganda, and the terror of shelling, produced scenes of mass suicide. The truce on Aka cannot be separated from that tragic backdrop. By late June, with the main battle winding down, the ceasefire allowed villagers and soldiers to avoid a final round of killing. The Cornerstone of Peace memorial in Okinawa records more than 240,000 names from that campaign. The stillness that followed the beach meeting kept Aka from being added to that roll in the final weeks of the war.

Rediscovery and commemoration eight decades later

The story might have stayed in family albums. In 2004, Japanese journalist and later university lecturer Hiroshi Sakai sat beside an elderly couple on a flight who told him they had been children on Aka. They remembered American and Japanese soldiers talking on a beach instead of fighting. Sakai began to search for documentation. In March 2024 he wrote to political geographer Nick Megoran, who had studied the 1914 Christmas truces, and attached a photograph that showed enemies kneeling together in prayer on the sand. Megoran has said the image changed how he saw that chapter of the war.

I was spellbound. I just sat there looking at it for a very long time and my eyes welled up with tears.

This year, on the eightieth anniversary of the events on Aka, islanders, descendants and researchers stood on the same beach. Pete Alston of Jesmond Parish Church led prayers in English and Japanese. An Anglican cleric spoke words that captured the mood of the day.

The men of both sides showed us that there is a better way than war.

Some younger residents had not heard the details until now. Older islanders still carry precise memories of those days. Family members of American participants traveled to the island, including children of Marines who had kept photographs and letters. Researchers recorded interviews with relatives and an eyewitness. The picture that emerges is complicated and human, a story that is hopeful without easy sentiment. Scholars who worked on the case caution against romanticizing the episode, since the garrison had also committed violence earlier in the battle. The value of the Aka story lies in what it reveals about choice, trust and restraint in a place where such acts were rare.

Quick Facts

- The truce on Aka Island took place in late June 1945 during the closing weeks of the Battle of Okinawa.

- United States Marine Lt Col George Clark led a small team that sought dialogue instead of a direct assault.

- Japanese prisoners accompanied the Americans and broadcast surrender appeals from boats with loudspeakers.

- Lt David Osborn swam ashore and helped set up a meeting with the garrison commander, Major Yoshihiko Noda.

- Negotiations on Utaha Beach included a shared meal of roast pork, canned rations and sweet potatoes.

- The Japanese could not issue a formal surrender without the emperor’s permission, but agreed to a tacit truce.

- Before departing, both sides joined in a short prayer for international understanding and peace led by a US chaplain.

- No further lives were lost on Aka between the truce and Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945.

- The Battle of Okinawa killed more than 240,000 people, more than half of them Okinawan civilians.

- The story came to light through research by Japanese and British scholars and was marked on the beach with a memorial gathering eight decades later.