What students are being offered this winter

Across Taiwan’s campuses, student groups and travel organizers are promoting winter break “exchange” tours to cities in China for prices that undercut ordinary travel. The offers are drawing a surge of interest, and a wave of concern. The fees are so low that students and analysts fear the trips are being subsidized and orchestrated to collect personal data, shape opinions, and channel participants into united front activities aimed at aligning Taiwanese youth with Beijing’s political goals.

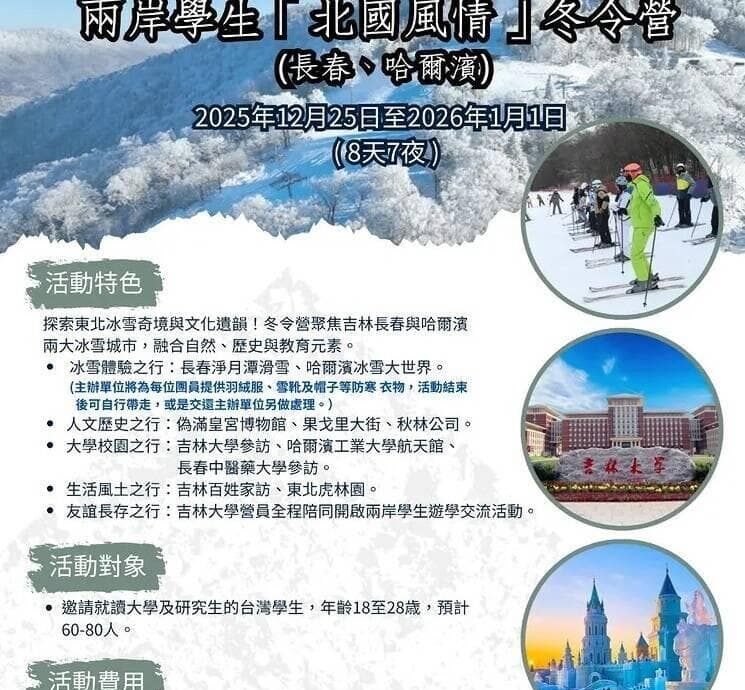

Packages start around NT$18,900 for an eight day itinerary that includes round trip airfare, accommodation, meals, insurance, and guided activities. Some early bird deals even add a free three day, two night visit to Hong Kong. One organizer with a long record of outreach to young Taiwanese advertises a Spring Rain Tour with tracks to Shanghai, Beijing, Harbin, and Chengdu. Fees listed for these routes range from NT$18,900 to NT$29,900. Students who book their own flights can pay as little as NT$7,900 to NT$9,900 for the land package.

Similar programs frame the experience as academics and culture. Itineraries often feature visits to prestigious universities such as Peking University and Fudan University, along with company tours and excursions to major cities. Yet schedules are frequently vague. A typical daily plan lists only broad activities like cultural lectures, youth forums, and exchange events across morning, afternoon, and evening blocks.

What is precise is the paperwork. Registration forms request extensive personal information that goes far beyond ordinary travel details. Students are asked to provide social media handles, campus leadership roles, prior trips to China, views on cross strait relations, and experiences interacting with Chinese students. Some have voiced worries that answers regarding national identity or a one China, one Taiwan stance could be logged and used to profile them. Several said they could not tell in advance whether officials would attend events, and that if united front activities occurred they would feel pressed to comply.

Why the prices and paperwork raise red flags

Travel math is one reason students are uneasy. Round trip airfares to Shanghai or Beijing vary by season, but airfare alone can consume a large share of the total advertised price in many of these offers. Accommodation, meals, buses, insurance, guides, and venue rentals all add costs. Delivering eight days of travel and activities at NT$18,900, or offering a free Hong Kong add on, suggests a backer is absorbing part of the bill. In the cross strait context, local Taiwan affairs offices, mass organizations, or partners linked to the United Front Work Department (UFWD) often sponsor youth exchanges. Subsidies are common because they serve a political purpose rather than an ordinary tourism goal.

Detailed questionnaires serve a purpose as well. Collecting social media accounts, campus positions, and stated views allows organizers to map networks, identify potential influencers, and tailor follow up outreach. In many cases, these programs are not one off tours. Participants are encouraged to return for internships, pitch startup ideas, or join forums that reinforce favorable impressions. The result is a pipeline that cultivates a cohort of young Taiwanese who feel connected to China’s institutions and narratives.

These tours also fit a broader strategy. Beijing pairs military pressure with a large nonmilitary playbook that seeks to win hearts and minds. United front work is the centerpiece of that approach. It targets different segments of Taiwan’s society with cultural exchanges, scholarships, travel, and media content that frame China as modern, friendly, and familiar. The goal is to weaken resistance to Beijing’s political objectives by building personal ties and emotional identification over time. In recent years, the strategy has put special emphasis on youth, using universities, city governments, and quasi civic groups to carry out people to people programs that feel social, not political.

How united front work targets youth

The UFWD is a Chinese Communist Party organ that operates at home and abroad. It was built to influence groups outside the party, and it has expanded under Xi Jinping. For Taiwan, its methods blend hospitality and messaging. Students are welcomed into tightly managed settings, hosted at top campuses, and guided through sites that convey a narrative of cultural closeness and national rejuvenation. Participants are prompted to share impressions on social media or speak at forums after returning home. The messaging is careful and consistent. It emphasizes opportunity in China, downplays political differences, and presents unification as a natural outcome of shared heritage and economic logic.

The approach echoes classical thinking about persuasion. Chinese strategist Sun Tzu is often cited in discussions of psychological pressure and political warfare. He stressed that the most effective victory is won by shaping the opponent’s will.

Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War, wrote that “to attack the heart is the best.”

United front work is described inside China in strikingly candid terms. The agency responsible for cross strait policy has referred to united front work as a core tool of party strategy.

China’s Taiwan Affairs Office has described united front work as “an important magic weapon for the Communist Party of China to unite people and gather strength.”

Practical programs reflect this outlook. Beyond tours, students are offered internships, startup grants, and collaboration with influencers and cultural groups. Digital platforms carry lifestyle content that blends entertainment with nationalism. The full picture is not overtly political. It is meant to feel friendly and aspirational. That is why travel deals that seem too good to be true still draw sign ups even when the political context is widely known.

What recent investigations have shown

Reporting and independent documentaries in Taiwan have traced how these exchanges work behind the scenes. A widely viewed film released in late 2024 followed the recruitment of Taiwanese creators and students through cultural events, all expenses paid trips, and networking dinners. Organizers encouraged participants to apply for PRC identification documents and to join groups linked to the united front system. Influencers were asked to produce content that showcased China in a favorable light, sometimes with messaging that tracked closely with official narratives.

Another investigation chronicled a “free” trip for Taiwanese aged 18 to 40 that began with a bus ride from Macau into Guangdong. Participants expected beach time in Hainan. Instead, the itinerary changed daily and centered on symbolism. A lavish banquet hosted by local party officials set the tone. The group was taken to Zhanjiang Naval Base, where guides highlighted modern warships and China’s resolve on Taiwan. At the Chenbin Memorial Hall, an ideological lecture recast Taiwan’s Indigenous history to fit a unification story. Afterward, state media packaged photos and testimonials to present young Taiwanese as enthusiastic supporters of national unity. Travelers paid their own airfare. Local offices covered nearly everything else.

Targeting does not stop at students. In recent years, invitations have gone to village heads and other grassroots figures in Taiwan. Some trips included political instructions, sometimes tied to local elections. Investigations also uncovered cases where local invitees held PRC citizenship, a legal problem in Taiwan. The net effect shows a pattern. Subsidized visits produce favorable content, contacts are added to political networks, and those willing to echo Beijing’s lines gain access to future programs.

How authorities in Taiwan are responding

Taiwan’s government has sharpened its response to influence campaigns packaged as education or cultural exchange. The Ministry of Education recently barred Taiwanese universities from collaborating with three mainland institutions connected to the UFWD. It also announced that degrees from those schools would not be recognized in Taiwan. Officials said the target was not normal scholarly contact, but schools structured to advance political missions through academia. Critics, including opposition lawmakers, argue the bans restrict useful channels of contact and harm academic options for students. The debate underscores the difficulty of separating legitimate exchange from political programming.

Education Minister Cheng Ying-yao framed the decision in terms of academic integrity, not isolation. He said the banned institutions were serving a political function instead of a scholarly one.

Cheng Ying-yao, Taiwan’s Minister of Education, said the banned universities serve a political purpose rather than a purely academic one.

At the national level, Taipei has rolled out a package of measures to counter united front threats. Government agencies have promoted media literacy and fact checking, updated rules on foreign influence in education and civic groups, and coordinated with local governments to spot suspicious outreach. Taiwan’s Anti Infiltration Act, which took effect in 2020, criminalizes receiving funds or instructions from hostile foreign forces to influence politics, elections, or public opinion. Digital security guidance now warns students and public officials about data harvesting through apps and sign up forms linked to foreign political entities.

The policy trend is clear. Authorities are trying to keep space for genuine academic and cultural interaction while closing channels designed for covert political aims. That is not easy in an open society where travel is popular, young people are curious, and many students want to see China for themselves.

Advice for students and universities

Visits to China can be valuable for language, culture, and personal networks. The challenge is to tell a normal exchange from a political program. Students and administrators can lower risk through careful checks before saying yes to a trip.

- Verify who is organizing and paying. Ask for the legal entity name of each sponsor, not just a brand label. Request a breakdown of what costs are covered and by whom.

- Insist on a full itinerary with named hosts and addresses. Avoid programs that keep daily schedules secret or change plans without explanation.

- Limit personal data in applications. If a form asks for social media logins, political views, or campus positions, ask why it is necessary and how data will be stored, used, and shared.

- Watch for deliverables. Be cautious if organizers expect speeches, testimonials, or social posts that echo political themes.

- Clarify access to officials. Ask whether government departments or party affiliated groups will attend events or meetings.

- Travel with informed consent. Share the itinerary with your university’s international office and family. Keep emergency contacts and consular information handy.

- Practice digital hygiene. Use separate accounts or devices if you must install unfamiliar apps. Turn off unnecessary permissions and location tracking.

- Know Taiwan’s laws. Do not accept funds or instructions from foreign political entities to engage in advocacy or election related activity.

What to Know

- Low cost winter tours to China targeting Taiwanese students bundle airfare, lodging, meals, and guided activities at prices that suggest subsidies.

- Itineraries are often vague, while application forms seek detailed personal data, including social media accounts and views on cross strait relations.

- Experts identify these programs as part of united front work, a party led strategy that seeks to shape attitudes and build networks across Taiwanese society.

- Investigations have documented subsidized trips that feature political messaging, military showpieces, and state media use of participant images and quotes.

- Taiwan’s Ministry of Education has barred cooperation with three mainland universities linked to the UFWD and will not recognize degrees from them.

- Officials emphasize media literacy, updated regulations, and legal tools such as the Anti Infiltration Act to counter covert influence.

- Students can reduce risk by verifying sponsors, demanding full itineraries, limiting personal data, and avoiding programmed political deliverables.

- The core issue is not travel itself, but whether exchanges are designed to collect data and cultivate political alignment rather than genuine academic or cultural learning.