From language classrooms to power and partnerships

Miradie Tchekpo recently turned a classroom dream into a paycheck. The Beninese graduate studied Mandarin and trained at the Confucius Institute at the University of Abomey Calavi, then won a job as an interpreter for a Chinese trading company in Cotonou. She hopes to broker exports from Benin to Chinese buyers and import Chinese goods that can serve local markets. Her story captures the promise, and the questions, that surround China funded language programs across the continent.

- From language classrooms to power and partnerships

- What are Confucius Institutes and how do they operate

- How big is the footprint in Africa

- Promise and limits for African students

- Why critics worry about academic freedom

- Beyond the classroom, culture, media and ideas

- What do African stakeholders want to see

- Risks and opportunities for local culture

- Making language learning count for jobs

- Key Points

Since the first Confucius Institute opened in 2004, China has built a vast cultural footprint overseas. Across Africa, institutes or classrooms now operate in most countries, offering language courses and cultural activities. South Africa hosts the largest cluster, with ten institutes, and Mandarin is appearing in both private and public school timetables. Even small states like Lesotho count more than one site. These centers are the visible side of a wider outreach that includes scholarships, training, museums, film partnerships, media projects, and policy exchanges.

Soft power often means shaping preferences through culture, education, and persuasion. In Africa, Beijing’s soft power centers on Mandarin classes, scholarships to Chinese universities, and a steady calendar of cultural events. The approach aims to make cooperation with Chinese entities feel straightforward, while deepening long term ties in trade, technology, and politics.

What are Confucius Institutes and how do they operate

Confucius Institutes are partnerships between a host university, a Chinese partner university, and a central office under China’s Ministry of Education. For years that office was known as Hanban, now reorganized as the Center for Language Education and Cooperation. The Chinese side supplies funding, teaching materials, and instructors, while the African partner provides classrooms, local staff, and access to students and communities. Many institutes also run Confucius Classrooms in primary and secondary schools. Courses usually focus on Mandarin language and cultural practices such as calligraphy, music, and cooking.

Funding and governance

The joint model places a foreign government funded program inside an African campus. Contracts set out the division of roles, the hiring and pay of visiting teachers, and the scope of activities. Instructors sent from China typically follow curricula and guidelines approved by the Chinese partner, with the local university accrediting or hosting the courses. This structure, which is different from external cultural centers like the British Council or the Goethe Institut, gives Confucius Institutes unusual proximity to academic life. Supporters say this keeps costs low and boosts access. Critics say it blurs lines between cultural outreach and political influence, especially if certain topics are avoided.

Why many African campuses welcomed them

Many African universities face tight budgets, crowded classrooms, and limited language options. Confucius Institutes arrive with teaching materials, trained instructors, and, in some cases, new buildings. For students, Mandarin can feel practical. It opens doors to Chinese suppliers, investors, and partners. Ghana’s University of Cape Coast, for example, has described high demand for classes, with thousands enrolled per term. Local managers often present the aim in simple terms, to equip students with communication tools that make business and academic exchanges with Chinese counterparts more effective.

How big is the footprint in Africa

Across the continent there are now more than 50 Confucius Institutes and dozens of affiliated classrooms, with programs operating in 49 African countries. South Africa’s network includes institutes at major universities and Mandarin as an elective in many schools. Lesotho, with a small population, hosts two institutes. The reach looks even broader at the grassroots level, with institutes offering public classes, weekend programs, and cultural festivals.

Student flows match that expansion. The number of Africans enrolled at Chinese universities climbed from fewer than 2,000 in 2003 to more than 81,500 by 2018. China has offered many scholarships and grants, and created university pairing schemes that link African institutions with Chinese partners for long term collaboration. These links promise language skills, research exchanges, and easier access to Chinese labs and libraries.

Country snapshots show the everyday impact. In Burundi, an institute at the national university has drawn more than 6,000 learners since 2012. In Ghana, institute leaders report thousands of students each term. South African language schools that once focused on English now offer Mandarin, often tapping instructors trained through Confucius Institutes. The footprint reaches beyond campuses into community centers, schools, and local businesses.

Promise and limits for African students

The educational offer is tangible. Students gain language skills, cultural exposure, and a pathway to study in China. Many view Mandarin as a practical skill for logistics, tourism, manufacturing, or retail supply chains. Yet the economic payoff is uneven. Social scientist Simbarashe Gukurume has observed that while Confucius Institutes grow China’s cultural presence, job opportunities for African graduates in China remain scarce. On large projects in Africa, Chinese firms often bring in their own work crews, and African graduates of Mandarin programs frequently find the most reliable path is teaching the language at home.

Staffing at some institutes reflects that reality. At the University of Zimbabwe, for example, most Confucius Institute instructors are local academics who first studied in China with financial support, then returned to teach Mandarin. Gukurume and other scholars argue that cultural and education programs often travel alongside bilateral deals in mining and infrastructure that can tilt access to resources toward Chinese firms. That link, they say, deserves close scrutiny and strong local oversight.

There are clear success stories as well. In Bujumbura, 25 year old teacher Bankuwiha Etienne described how seeing a local Mandarin instructor changed what his students thought was possible.

My students are very excited and they are very motivated, because they see me as a role model, an example, maybe an idol. Because when they see me teaching them Chinese, they get ideas in their minds. They say, I am a Burundian like my teacher, so if I put effort like my teacher, maybe I will get to his level. That is why they are very encouraged and they love learning Chinese.

Etienne also sees cultural bridges forming through daily contact.

I can be a bridge between Africa, my people, and the Chinese, my new people.

Yan Ping, director of the institute in Burundi, said everyday greetings capture the change she hears in the streets.

Not only are the students here interested in the Chinese language, the Chinese culture, but also their teachers. For me if I walk on the streets I hear people greeting me by saying Ni Hao. The first time it really touched me.

These personal accounts show why demand is strong. They also help explain why many African institutions judge that the benefits in skills and contact outweigh the risks, as long as contracts and content stay transparent and balanced.

Why critics worry about academic freedom

Confucius Institutes sit at the center of a global debate about influence inside universities. In several Western countries, universities closed or restructured these programs after complaints about pressure to avoid sensitive topics, or concerns about who controls content, staff, and events. The core claim from critics is that the institutes can present a state approved narrative, and that this can chill open discussion about Tibet, Taiwan, Tiananmen, and other politically charged subjects.

Matt Schrader, a China analyst who has studied influence operations and university partnerships, summed up the concern this way.

They are platforms for an authoritarian party that is fundamentally hostile to liberal ideas like free speech and free inquiry to propagate a state approved narrative.

Rights groups go further. In a 2019 report, Human Rights Watch argued that institute hiring and course material can reflect political tests rather than academic criteria.

Confucius Institutes are extensions of the Chinese government that censor certain topics and perspectives in course materials on political grounds, and use hiring practices that take political loyalty into consideration.

There have been publicized incidents. At an academic gathering in Portugal in 2014, conference materials were reportedly altered to remove references to Taiwan. In the United States, speakers have said their biographies were edited at the request of institute staff to delete mentions of Taiwan. In Australia, a state education department ended institute linked programs in public schools after a review warned that having appointees of a one party state embedded in a democratic government department could erode public trust. Several universities in Europe and North America later closed or reshaped their programs.

Supporters answer that many institutes teach language and culture, not politics, and that host universities keep academic control. Some university administrators in countries with stricter scrutiny have said their Confucius Institute work is straightforward language teaching without any impact on academic freedom. Across much of Africa, the reception has been different from the West. With scarce funding and strong student interest, campuses often see the institute model as an acceptable way to add a new field of study, provided local oversight remains firm.

Beyond the classroom, culture, media and ideas

Language centers are only one pillar of China’s outreach. Chinese agencies and companies have financed or supported theaters, museums, film festivals, media training, and library projects in several African countries. Broadcasters have expanded their African operations and teamed up with local outlets, while journalism exchanges bring reporters to Chinese newsrooms. The goal is simple, to tell China’s story in a positive light and to strengthen cooperative ties with African institutions.

Policy exchange has grown as well. The Forum on China Africa Cooperation has become a fixture of African diplomacy with Beijing. A linked track of think tank and academic forums, including the China Africa Think Tanks Forum, brings researchers and officials together under Chinese sponsorship. Attendance at top level summits is high, and the optics matter, for example, 51 African heads of state participated in the 2018 Beijing summit. These gatherings help set the tone for cooperation in trade, technology, and governance. They also create personal networks that ease later deals, a practice Chinese officials often describe in terms of guanxi, the cultivation of trusted relationships.

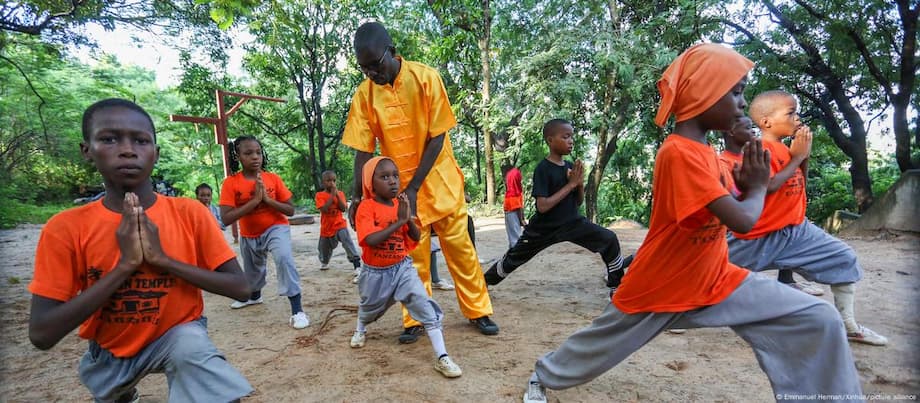

China has invested in leadership schools and training programs that present its development approach as a learning model. The Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Tanzania is a prominent example, financed with Chinese support to host political and administrative training for African parties and officials. Together, culture, media, think tanks, and training feed into a broad strategy that seeks influence through steady, long duration engagement.

What do African stakeholders want to see

As China’s cultural and academic presence has grown, African scholars and cultural leaders have pressed for a stronger local voice in how these relationships work. Researcher Avril Joffe cautions that a heavy Chinese cultural presence can crowd out regional content. She argues for a policy posture that protects African agency, keeps cultural space open, and makes sure outside programs do not erode democratic values or local control.

One proposal is to reduce dependence by expanding domestic scholarships and cultural funding. Another is a continental approach to negotiations. If the African Union sets baseline standards and helps coordinate contracts, national ministries could bargain from a stronger position. That could make it easier to insist on transparency, shared governance, and space for African languages and arts inside every partnership.

- Publish Confucius Institute agreements and submit them to parliamentary or university senate review.

- Create joint academic committees that include student and faculty representatives with the power to approve or veto curricula and public events.

- Set clear safeguards for academic freedom, including clauses that protect discussion of all topics in classes and on campus.

- Diversify study abroad and language options so Mandarin grows alongside Arabic, Portuguese, French, Swahili, and other languages that serve regional needs.

- Tie scholarships to return service in local sectors such as health, logistics, and engineering to convert study into public value.

- Establish data reporting on student outcomes, hiring, and local supplier use for Chinese projects, then make those reports public.

- Use regional bodies such as the African Union and the African Continental Free Trade Area to coordinate standards and reduce country by country bargaining gaps.

Risks and opportunities for local culture

Mandarin classes and Chinese festivals can spark curiosity and widen horizons. They can also tilt airtime and funding away from African stories if not balanced. Joffe’s work notes that Chinese investment in festivals, exhibitions, and media can outspend local producers. Without matching local support, African filmmakers, musicians, and writers can lose slots in programs that shape taste and memory.

There are practical ways to keep space open. Co programming that pairs Chinese and African artists can keep local voices in the spotlight. Grants can require a share for local content. University partnerships can include translation training for African languages, not only Mandarin. National arts councils can track the mix of content at publicly supported festivals. Small steps like these help ensure that cultural exchange remains a two way street.

Making language learning count for jobs

For many young Africans, the key test is simple, does Mandarin help secure better work. Policymakers and universities can tilt the answer toward yes by pairing language with sector skills. A logistics student with Mandarin can track shipments with Chinese suppliers. An engineer with Mandarin can coordinate with Chinese equipment vendors. A tourism graduate with Mandarin can guide Chinese visitors at heritage sites.

Work integrated learning can help. Structured internships with Chinese companies in Africa should include clear labor protections, local content rules, and a path to hiring. Job centers can match Mandarin graduates with African firms that trade with China. Public procurement can require foreign contractors to fund language and technical apprenticeships for local staff.

Career pathways matter too. Business councils that link African and Chinese entrepreneurs can mentor students. Alumni networks of African graduates from Chinese universities can help with job leads and project pitches. Universities can certify language plus professional skills as a combined credential that signals immediate workplace value.

Key Points

- China has built more than 50 Confucius Institutes in Africa, with programs active in 49 countries and growing enrollment.

- South Africa hosts ten institutes, and Mandarin is offered in many private and public schools across the country.

- Scholarships have sent tens of thousands of Africans to study in China, with 81,500 African students enrolled there by 2018.

- Critics warn that institute rules and practices can chill discussion of sensitive topics and blur lines between culture and politics.

- Rights groups and analysts say some institutes promote a state approved narrative, while universities in Africa often emphasize language and culture instruction.

- China’s outreach also includes theaters, museums, media ties, think tank forums, and leadership training programs.

- Researchers urge African governments and universities to publish contracts, protect academic freedom, and expand domestic funding to keep cultural space open.

- Pairing Mandarin with sector skills, internships, and local hiring rules can increase the job value of language study.