In Gansu, two energy systems grow side by side

Across the Hexi Corridor on the edge of the Gobi Desert, wind turbines and solar arrays now span the landscape in long shimmering rows. The corridor’s steady winds and vast plateaus have turned Gansu into one of China’s most important bases for renewable electricity. Yet just beyond the dunes, towering stacks mark another power source that remains central to the national grid. At Gansu’s Changle Power Plant, a sixth one gigawatt coal unit has entered service, lifting the complex to 6 gigawatts of capacity. That single site can supply electricity comparable to the needs of a small country, a reminder that China’s energy transition is being built on two tracks at once.

- In Gansu, two energy systems grow side by side

- How many new coal plants are still being built?

- Why coal persists despite a record boom in renewables

- Is new coal actually running more, or just running differently?

- Regional cases, from Gansu to Inner Mongolia

- What would speed the shift away from coal?

- The global picture and why China matters

- Key Points

Officials often describe coal as a safety net for a power system that is rapidly adding wind and solar. The stability argument is straightforward. Solar output plunges at night and can dip during sandstorms or cloudy weeks. Wind can swing with seasonal patterns. Coal units, by contrast, can dispatch around the clock when fuel is available. The balance is delicate. In 2021, a power crunch prompted rationing and factory slowdowns across several provinces. Keeping enough dispatchable capacity on the system has become a priority, while the country also pushes hard to cut emissions.

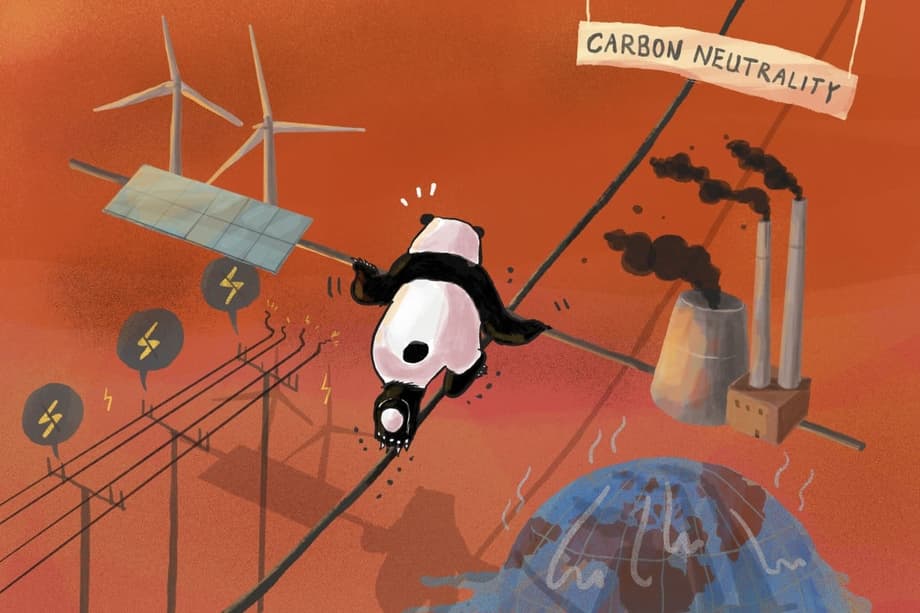

China has pledged to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060. Those goals are driving record investment in clean technology. They also sit alongside a wave of new coal power projects that local authorities frame as insurance for energy security and as anchors for industrial growth. The paradox is sharpest in places like Gansu, where solar and wind build at record pace, and mega coal plants still expand to backstop the grid.

How many new coal plants are still being built?

Analyst tallies show a powerful rebound in coal construction activity. In 2024, builders started 94.5 gigawatts of new coal power projects and restarted 3.3 gigawatts that had been on hold, the highest level in a decade. Permits for new capacity reached 66.7 gigawatts in 2024, with approvals picking up in the second half of the year after a slower start. New proposals, while down from the surge of 2022 and 2023, still came to 68.9 gigawatts. China accounted for the vast majority of new global coal construction starts that year. Retirement of old units has lagged, falling from about 13 gigawatts in 2020 to roughly 2.5 gigawatts in 2024.

Coal’s share in the grid remains large, yet it is slowly shrinking as clean power expands. China added about 356 gigawatts of wind and solar capacity in 2024 alone, several times the annual additions in Europe. By late 2024, installed solar capacity approached 890 gigawatts and wind capacity close to 520 gigawatts according to research groups, while the coal fleet remained near 1,200 gigawatts. In June 2025, coal’s share of power generation fell to near 51 percent, its lowest in nine years, while renewables rose to about 60 percent of installed capacity. These figures show both the speed of clean power growth and the scale of coal that still sits on the system.

The construction pipeline means many new coal units will enter service in the next two to three years. That has stoked concern that new capacity will crowd out renewable electricity, especially in provinces where grids and markets still give coal favorable treatment. Whether capacity additions translate into higher coal burn hinges on how the power system is run, not simply on how many stacks are built.

Why coal persists despite a record boom in renewables

China’s clean power boom has been extraordinary, yet coal keeps its footing for reasons that go beyond pure generation need. Provincial leaders carry the memory of past shortages. Power planners must deal with fast rising summer peaks. Grid rules and contract structures still reward coal output in ways that are slow to change. Together, those forces have extended coal’s role even as clean power is capable of covering much of incremental demand growth.

Energy security after the 2021 power crunch

The shortages of 2021 were a shock. A surge in demand, coupled with high coal prices and rigid retail tariffs, left plants unwilling or unable to produce at a loss. Several provinces implemented rationing. Lights went out in some districts and factories curtailed shifts. While reforms since then improved dispatch and pricing, many local governments moved to approve new coal units as insurance. The goal was to build a buffer that could respond to extreme weather, long lull periods for wind and solar, and further demand spikes from industry or households.

Grid bottlenecks and contracts that favor coal

Even where clean electricity is plentiful, it does not always reach the market. Long term contracts and minimum purchase quotas for coal power still shape dispatch in a number of provinces. Analysts estimate that renewable curtailment rose in late 2024, with a curtailment rate around the mid single digits, and is often higher in interior regions where transmission to coastal demand centers is constrained. Many buyers are locked into contracts that require them to take a fixed quantity of coal power, even when wind and solar are available at lower cost.

Qi Qin, a China analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, summarized the bind clean generators face when contracts and quotas hold up grid access.

More solar and wind should be integrated into the power grid, but it was not because of these agreements.

Another reason for coal’s persistence is finance and industrial policy. Coal mining companies have backed a large share of newly approved plants, securing long term demand for their output and supporting local employment. Provincial governments often promote new units for economic development, with coal plants serving as anchors for energy intensive projects in chemicals, metals, or data processing. Without market reforms that reward flexibility and prioritize least cost generation, these incentives keep coal in the center of the system.

Is new coal actually running more, or just running differently?

Capacity is not the same as generation. In recent years, clean power additions have covered most, and in some periods all, of China’s growth in electricity demand. Coal’s role has been to fill the gap between total demand and the combined output from hydro, nuclear, wind, and solar. When that gap narrows, coal generation can flatten or fall even if new coal units are being built. Researchers see little correlation between new coal capacity and higher coal burn. Instead, utilization hours across the fleet tend to drop as more plants compete for fewer running hours.

Policy sets the target for coal to play a flexible supporting role. In practice, many plants still operate as if they are baseload units. Technical constraints, such as minimum stable load thresholds and slower ramp rates, limit how low a unit can go and how quickly it can respond. Contractual obligations and capacity payment designs also incentivize output rather than flexibility. Retrofitting plants for deeper and faster ramping, expanding storage, and advancing market based dispatch are the keys to unlocking coal’s intended backstop role.

Experience since the shortages shows that investments in grid operation, cross provincial transmission, and storage, combined with better demand response, can keep the lights on even in stress periods. Those improvements reduce the need to build more coal units for reliability. When clean power covers new demand and the system is operated flexibly, coal generation can fall while reliability improves.

Regional cases, from Gansu to Inner Mongolia

Gansu offers a vivid example of how renewables and coal now move together. The Changle complex, at 6 gigawatts, is the largest coal plant in the province. Local officials frame it as a stabilizer for a grid rich in wind and solar. During long winter nights or still periods, its turbines fill gaps that batteries and pumped hydro cannot yet cover at scale. The plant’s expansion, announced in late 2024, came alongside continuing growth in Gansu’s wind and solar bases that export power to the east.

In China’s coal heartland, a mega plant known as Yushen Yuheng has been cited as a consolidation model. It is replacing hundreds of megawatts of small, inefficient units with larger, higher efficiency supercritical units. The project also integrates on site renewable capacity, with dozens of megawatts of wind and a few hundred megawatts of solar, and includes a carbon capture facility designed to trap about one hundred thousand tons per year. The concept is to deliver more reliable power with lower unit level emissions while clearing older stock from the system.

Inner Mongolia shows a different type of experimentation. A large coal to chemicals complex operated by a state owned power company has added a green hydrogen line and a dedicated wind and solar plant of about 150 megawatts. The goal is to cut the carbon intensity of hydrogen and synthesis gas for downstream products such as ammonia and methanol. While this does not decarbonize power generation, it points to a route for heavy industry where renewables replace a portion of coal input over time.

Green hydrogen is promising for steel, chemicals, and long duration seasonal storage, but its use in day to day power generation remains limited. Electrolysis requires abundant low cost electricity and significant infrastructure for transport and storage. Analysts estimate green hydrogen still costs more than grey hydrogen made from fossil fuels in China. Co firing ammonia in coal plants can cut emissions, yet even a ten percent blend can make electricity far more expensive than running coal alone. For the next five years, expanding wind, solar, storage, transmission, and demand management offers a cheaper path to displace coal at scale, while hydrogen pilots continue to mature for industry and backup storage roles.

What would speed the shift away from coal?

Analysts, grid experts, and many provincial planners point to a consistent set of fixes. The aim is to let clean power run whenever it is available, adapt coal to a flexible role, and give investors clear timelines for change. The next five year plan and updated climate targets can lock in that direction.

- Stop new approvals for conventional coal units that are not explicitly designed and contracted for flexibility.

- Accelerate retirement of older, inefficient plants and set targets to reduce average utilization hours of the fleet.

- Reform long term power purchase contracts that mandate minimum coal offtake and shift toward market based dispatch that prioritizes least cost generation.

- Expand spot markets and ancillary service markets so that flexibility, fast ramping, and voltage support are paid services.

- Upgrade transmission to carry more wind and solar from interior regions to coastal demand centers, and increase cross provincial trading.

- Scale batteries, pumped hydro, and demand response so that short duration variability is managed without calling on coal.

- Introduce capacity payment designs that reward flexible readiness rather than constant output.

- Align provincial incentives with national goals, including tax and finance reforms that reduce the pull from coal mining companies to sponsor new projects.

Political signals from international coal transition efforts also matter. Julie Dabrusin, Canada’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change and co chair of the Powering Past Coal Alliance, framed the direction at a climate gathering.

As the world moves towards low carbon energy and clean technologies to advance economic growth and a clean environment, the coal to clean transition is inevitable.

The global picture and why China matters

Coal power is in retreat in many regions, yet capacity continues to expand in Asia’s two largest economies. In the first half of 2025, China and India accounted for most of the new coal power commissioned worldwide. Europe and Latin America have little to no pipeline for new plants and are focused on retirements. The United States continues to retire coal units based on economics even as policy choices shift with elections. These global patterns put China’s choices in sharp relief because of the scale of its system and its influence on manufacturing and supply chains.

China is also the anchor of the global clean energy economy. It manufactures the vast majority of the world’s solar panels, dominates batteries and electric vehicles, and is scaling grid storage and high voltage transmission. Those exports reduce technology costs for the rest of the world and help countries in the Global South install renewables at speed. Clean energy added in China has already helped slow growth in national emissions by covering demand that would have gone to fossil fuels.

The coexistence of a booming clean power sector and a large coal fleet is the core of the story. If market and grid reforms keep pace with installations, clean power will run more hours, curtailment will fall, and coal generation will decline even if some new capacity enters service. If contracts and dispatch rules continue to favor coal, renewable output will be held back and emissions will stay higher than necessary. Given China’s size, the outcome will shape global coal demand and the pace of decarbonization worldwide.

Key Points

- Gansu’s Changle plant reached 6 gigawatts as the province expanded wind and solar, illustrating China’s two track energy strategy.

- In 2024, construction began on about 94.5 gigawatts of new coal capacity and 3.3 gigawatts resumed, the highest level in a decade.

- New coal approvals reached 66.7 gigawatts in 2024, while proposals fell from the peaks of 2022 and 2023 but remained high.

- China added about 356 gigawatts of wind and solar in 2024, and by mid 2025 coal’s share of power generation dipped to near 51 percent.

- Contracts and quotas for coal, along with grid bottlenecks, led to rising renewable curtailment despite record clean power additions.

- Analysts find new coal capacity does not automatically raise emissions, since utilization hours can drop as clean power grows.

- Coal mining companies finance a large share of new projects, reinforcing local economic incentives to keep building.

- Policy steps that would speed the shift include ending most new approvals, reforming contracts, expanding spot markets, and rewarding flexibility.

- China and India led new coal commissioning in early 2025, while Europe and Latin America advanced coal phaseout plans.

- China’s clean tech manufacturing lowers global costs, and domestic market reforms will determine how quickly coal gives way to renewables.