Alleged drone provocations and a failed martial law gamble

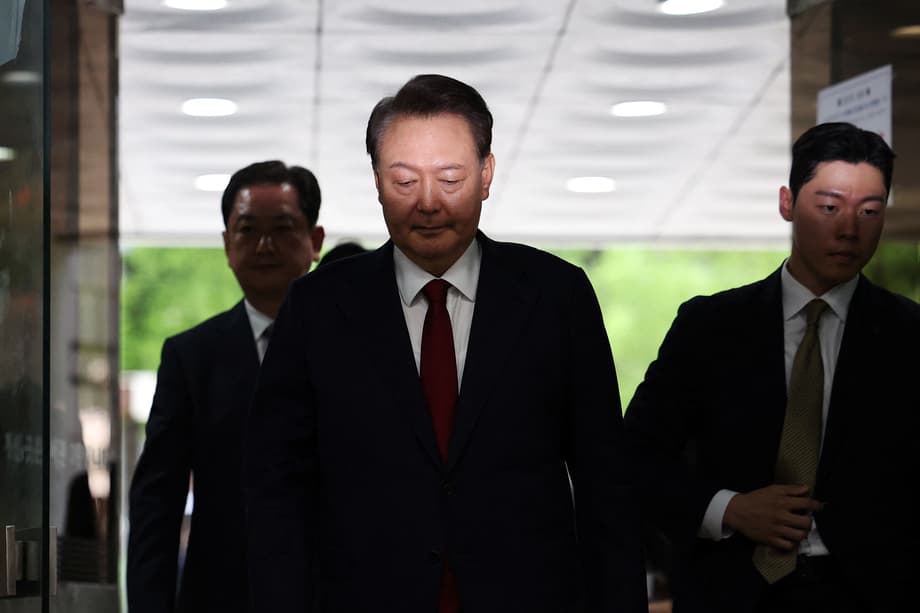

South Korea’s ousted president, Yoon Suk Yeol, has been charged with aiding an enemy state and abuse of power over an alleged scheme to send military drones into North Korea in late 2024. According to a special counsel, the flights were designed to provoke Pyongyang and create the appearance of a national security crisis that could justify Yoon’s emergency declaration of martial law on December 3. The martial law decree collapsed within hours after a tense standoff at the National Assembly, then came impeachment, arrest, and removal from office in April.

- Alleged drone provocations and a failed martial law gamble

- What prosecutors say happened

- How the December martial law attempt unfolded

- Why drones matter in the inter Korean standoff

- The charges and who is facing them

- Legal questions the court must decide

- What it means for allies and regional security

- At a Glance

Prosecutors say the case now rests on a trail of planning notes recovered from the mobile phone of a former counterintelligence chief, combined with testimony from whistleblowers inside the military drone unit. The memos describe a plan to manufacture instability through provocations that included drone penetrations of Pyongyang and other sensitive locations. North Korea had accused the South of leaflet drops by drone three times in October, and published images of a crashed unmanned aircraft it said belonged to the South. Investigators say the documents align with those claims and point to an intent to bait a response from Kim Jong Un.

Yoon denies ordering any drone incursions or attempting insurrection. He has said his martial law move sought to protect the country from anti state forces and to expose wrongdoing by political rivals. The former defense minister, Kim Yong hyun, and the then head of military counterintelligence, Yeo In hyung, were indicted alongside him. All three already face a separate trial for insurrection that carries the possibility of life imprisonment or the death penalty. The new indictment adds counts of aiding an enemy state and harming South Korea’s military interests.

What prosecutors say happened

The special counsel, appointed after Yoon’s removal, alleges that he and senior aides sought to ignite a low intensity cycle of confrontation that would make martial law appear necessary. A memo dated in October refers to creating instability and identifies targets where a North Korean reaction would be all but inevitable, including central Pyongyang and the port city of Wonsan. Another entry lists provocations by type, with the words drones and surgical strike highlighted among options.

The memo at the center of the case

Prosecutors say the memo came from the phone of Yeo In hyung, then head of the Defense Counterintelligence Command. It sets out a concept to force a loss of face in Pyongyang, and to seize any opportunity that might arise from a spike in tensions.

Investigators say the notes called to ‘create an unstable situation’ and to pick ‘targets like Pyongyang… so that a response is inevitable.’

Investigators also traced preparations for a nationwide emergency back to a military reshuffle in October 2023. The special counsel says these records, combined with flight information provided by whistleblowers at the Drone Operations Command, form a pattern that links the October and November 2024 incursions to the martial law planning.

Retired general and lawmaker Kim Byung joo told colleagues he was briefed that drones crossed into North Korea on October 3, again on October 8 to 9, and on November 13. He said the aim described by the whistleblowers was to elicit a retaliation that could justify emergency rule. South Korea’s defense leadership initially denied the North’s claim, then said the military could not confirm whether such flights occurred, a common stance when sensitive reconnaissance is at issue.

How the December martial law attempt unfolded

On the night of December 3, Yoon announced emergency martial law, said anti state forces had infiltrated the government, and ordered troops into the area around the National Assembly. Armored vehicles and soldiers moved to secure key sites while senior officials attempted to halt parliamentary activity.

Lawmakers convened through the night and voted to reject the decree. Civil society groups rallied outside the legislature. Military units that had been positioned around the complex did not proceed to make arrests inside. By morning, the government rescinded the order. Within weeks, prosecutors moved to charge top aides. In January, Yoon was indicted on directing a rebellion. In April, the Constitutional Court upheld his impeachment, removing him from office.

Yoon has insisted that he never set out to impose military rule. He argues he acted to protect democracy and to expose what he describes as anti state elements inside the opposition. A statement from his legal team called the new indictment one sided and said the former president was not informed of any drone flights. Former defense minister Kim faces related charges. Yeo has said he regrets not challenging the order.

Why drones matter in the inter Korean standoff

Drone incursions across the inter Korean border are dangerous because they are hard to detect and easy to deny. Low flying unmanned aircraft can slip past radar and can be used for reconnaissance, electronic warfare, or dropping small payloads such as leaflets. Airspace penetrations at the heart of Pyongyang would be viewed in the North as a serious violation of sovereignty.

The armistice that ended active fighting in 1953 created a demilitarized zone and set rules that both sides regularly test. There is no peace treaty. Under the armistice, military aircraft face strict limits near the border. If South Korean forces authorized drones to fly over Pyongyang, that would breach the spirit of the accord and could be treated by the North as an act of war.

Drone tensions escalated after North Korean units sent several drones into South Korean airspace in December 2022, including a small aircraft that reached the outskirts of Seoul. South Korea responded with warning shots, fighter scrambles, and its own reconnaissance flights north of the border. Public acknowledgment of such operations is rare, so investigators have leaned on device forensics and whistleblower accounts to piece together what occurred in October 2024.

Kim Byung joo, the retired general who sits in the National Assembly, cautioned about the danger of miscalculation.

“It was fortunate North Korea did not respond militarily. It could have escalated into conflict,” he said.

Analysts say Pyongyang’s decision to cut road and rail links and blow up two roads after the alleged October flights signaled anger without inviting a clash. Some believe the North’s deployment of troops to Russia and other operational priorities may have tempered its reaction. Drone flights by either side risk a fast cycle of retaliation that leaders may struggle to control.

The charges and who is facing them

The new indictment accuses Yoon of aiding an enemy state, abuse of power, and harming South Korea’s military interests. Prosecutors filed the same counts against Kim Yong hyun, the former defense minister, and Yeo In hyung, the former head of military counterintelligence. Both men were already detained over the martial law case.

Kim Yong dae, who led the Drone Operations Command, was charged with related offenses including obstruction of official duties and forgery, but was not arrested. Investigators say they limited conspiracy charges to officials with clear intent, and did not find evidence that lower ranking officers understood any link between drone flights and a plan for martial law.

Park Ji young, the spokesperson for the special counsel, said the alleged strategy increased the danger of armed conflict and harmed the country’s interests. Park also noted that some details remain classified because the memos and operational files contain military secrets.

Park said the defendants “conspired to create conditions for declaring martial law, increasing the risk of armed conflict and undermining national military interests.”

Legal questions the court must decide

To convict on aiding an enemy state, prosecutors must show that specific actions benefited North Korea or were intended to do so. The defense is expected to argue that the alleged provocations were designed to strengthen South Korean security, not to advantage Pyongyang, and that Yoon never ordered a drone incursion.

The insurrection charge focuses on intent and direction of the attempted power seizure on December 3. Judges will study whether Yoon and his aides coordinated the movement of troops against constitutional institutions, and whether the order amounted to an attack on the democratic system. South Korean law permits martial law during war or sudden turmoil, but the constitution requires the National Assembly be notified and gives lawmakers the power to cancel the order. That is what happened on the night of December 3.

If convicted on the most serious counts, Yoon could face life in prison or the death penalty. South Korea retains capital punishment in law, although executions have not been carried out since 1997. Sentencing would depend on the court’s findings about intent, command responsibility, and the degree of planning shown in the seized notes.

What it means for allies and regional security

Seoul’s alliance with the United States rests on close military coordination and strict civilian control of the armed forces. Any proven effort to manufacture a security crisis for domestic political gain would draw concern in Washington and Tokyo, both because of escalation risk and because it blurs the line between defense planning and politics.

The case also arrives amid rapid change in military technology around the region. Drones, low cost sensors, and precision weapons reduce the time leaders have to make decisions in a crisis. Mistaken assumptions about a small unmanned aircraft can trigger a spiral of mobilizations and counter moves. That danger is amplified on the Korean Peninsula, where the two governments remain enemies on paper and where the public lives with periodic standoffs.

At a Glance

- Special counsel indicts former president Yoon Suk Yeol on aiding an enemy state and abuse of power over alleged drone provocations

- Prosecutors cite phone memos and whistleblower accounts that describe plans to create instability and target Pyongyang

- North Korea reported leaflet drops by drone three times in October 2024 and later severed road and rail links

- Yoon declared emergency martial law on December 3, 2024, but lawmakers overturned it within hours

- Yoon was impeached and removed by the Constitutional Court in April 2025 and remains on trial for insurrection

- Former defense minister Kim Yong hyun and ex counterintelligence chief Yeo In hyung were indicted on the same new charges

- Investigators say lower ranking officers are not accused of joining any plot

- Conviction could bring life imprisonment or the death penalty under South Korean law