A turning point for the hinterland

Inland China is moving into the spotlight. Large metropolitan areas far from the coast are racing ahead with new rail hubs, industrial parks, and technology clusters. Projects that once appeared only in Shanghai or Shenzhen now feature in Wuhan, Chongqing, Chengdu, Hefei, and Zhengzhou. The shift did not happen overnight. It reflects two decades of targeted investment and a new emphasis on metropolitan clusters that spread jobs and services beyond the coast.

- A turning point for the hinterland

- What is powering inland momentum

- Wuhan sets the pace for intelligent vehicles and optics

- Chongqing rides logistics and manufacturing scale

- Qinghai and Xining show both promise and strain

- Are gaps starting to close

- Human capital and foreign investment matter more than ever

- How researchers track change from space and in city accounts

- Why Wuhan and Chongqing moved faster than others

- The hard part ahead

- Equity, cohesion, and national objectives

- At a Glance

Wuhan, Chongqing, and Xining show both the momentum and the limits of this new map of growth. Wuhan is shaping rules for driverless cars and building on strengths in optics and electronics. Chongqing has grown into China’s fourth largest city economy and a trade gateway linking the Yangtze River basin with markets to the west. Xining, the capital of Qinghai, sits atop vast solar and wind resources and one of China’s richest lithium basins, yet it struggles to recruit skilled workers because of altitude and distance.

National policies aim to narrow gaps that widened during the early export boom. Programs such as Go West and the Rise of Central China channeled funds into railways, highways, power grids, and industrial zones. A newer approach, dushiquan, connects cities into clusters with frequent trains and shared services, while East West Collaboration pairs rich coastal cities with poorer areas to transfer know how. The gains are visible in infrastructure and incomes, although a weaker economy and softer consumer demand could make the next stage harder.

What is powering inland momentum

Geography shaped China’s uneven development for decades. A line drawn from Heihe in the northeast to Tengchong in the southwest, often called the Hu Line, separates the dense and fertile east from the higher, drier west. The coast won early from export led growth and fast foreign investment. The interior had longer distances to ports, tougher terrain for highways, and fewer industrial anchors. That disadvantage started to change as the state financed trunk railways, inland river ports, and power lines, lowering transport and energy costs for factories away from the coast.

Population policy also matters. The household registration system (hukou) once limited labor movement and access to services in big cities. Gradual easing and local reforms in many inland hubs opened doors for migrants and college graduates to settle, start companies, and buy homes. Provinces in central China, including Hubei and Anhui, built on strong university systems to train engineers and managers, giving local firms a deeper talent base than a decade ago.

From Go West to metropolitan clusters

The inland agenda has evolved. Early programs focused on big ticket infrastructure and tax breaks. Current plans promote city clusters that share airports, research labs, and supply chains, making regions more than the sum of their parts. Fast trains now link cities across Hubei and Sichuan in under two hours, which expands labor markets and lets suppliers serve multiple factories in a day. These connections help inland firms climb into higher value activities, not only assemble parts shipped from the coast.

Pairing richer and poorer regions

East West Collaboration pairs cities such as Shenzhen or Shanghai with counterparts in the interior. The goal is to transfer management practices, digital tools, and industry contacts, not just money. Inland governments also court relocation of suppliers from coastal clusters that now face higher costs. That relocation can raise productivity inland when it comes with training and quality control standards rather than just moving low wage work.

Wuhan sets the pace for intelligent vehicles and optics

Wuhan has combined a deep university ecosystem with a manufacturing base that spans autos, electronics, and biomedicine. The city passed local rules to guide testing and deployment of intelligent connected vehicles, setting liability standards and data requirements. Those rules help firms move from pilot projects to commercial services in freight and public transport, with local roads and industrial parks designated for large scale testing.

At the core of this growth is the East Lake High Tech Development Zone, widely known as Optics Valley. It is a dense cluster of optoelectronics, medical devices, renewable energy equipment, and high end machinery. The zone contributes a large share of Wuhan’s output and hosts thousands of firms that feed into national supply chains. A large student population and research labs give local companies a steady stream of engineers and technicians. That depth is a major reason the city can move early on complex technologies such as lidar and vehicle to everything communications.

Hubei province has benefited from this mix of education and industry. It has ranked among faster growing economies in recent years, with per capita income that exceeds the national average for many urban districts. Local officials argue that linking research grants to commercialization has sped the path from lab to factory floor, especially in optics and sensors that now serve both autos and medical imaging.

Chongqing rides logistics and manufacturing scale

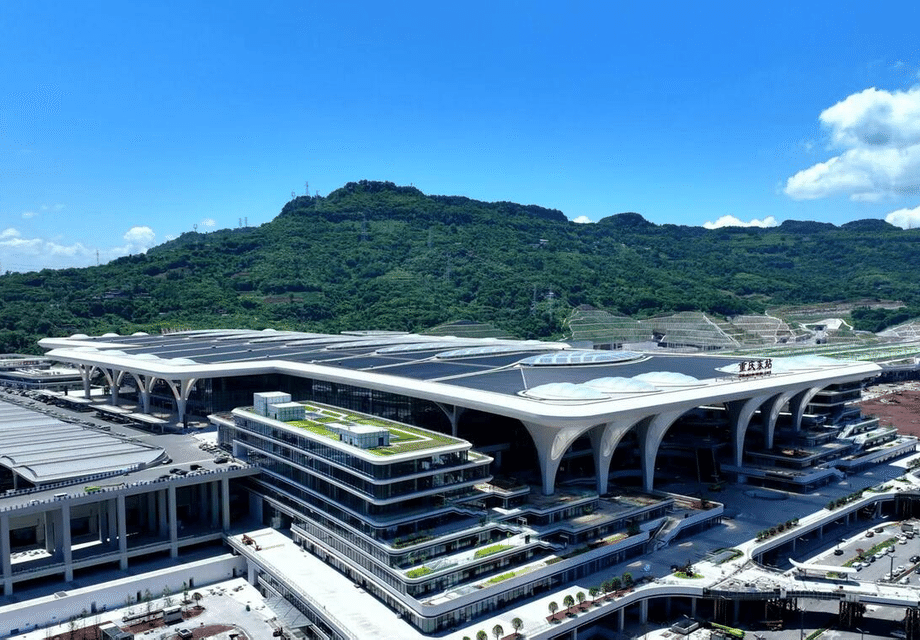

Chongqing’s rise rests on location and scale. It sits on the upper Yangtze River and anchors a highway and rail network that connects factories to ports on China’s coast and land routes across Central Asia. The city’s new Chongqing East station is billed as the world’s largest high speed rail hub, adding capacity for millions of trips a year and tightening ties across the southwest. Those links reduce travel times for workers and cut delivery times for parts and finished goods.

Manufacturing is the backbone. Autos, electronics, and machinery dominate local output. City data show disposable incomes in Chongqing above the national average, which helps local consumption support growth. The city also serves the Belt and Road Initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt by handling westbound trains to Europe and river traffic to the coast. That logistics role draws warehouses, parts suppliers, and export service firms, which deepens the ecosystem that manufacturers need.

Challenges are real. Local carmakers still import some high end components, and the city competes with coastal clusters for senior engineers and software talent. Policy makers are trying to grow talent pipelines through vocational colleges and joint programs with major firms. The near term test is whether inland producers can move up in software, chips, and advanced materials while keeping costs competitive.

Qinghai and Xining show both promise and strain

Qinghai is rich in sun and wind and has one of China’s largest lithium resources. That gives it a natural role in solar farms, battery materials, and low cost power for data centers. Xining has pitched itself as a site for energy hungry computing because cool temperatures and green power can lower costs and emissions. Grid links to the east help sell excess power to coastal provinces during peak demand.

Yet the province faces structural constraints. Thin air and cold winters can make recruitment harder, and the distance to large consumer markets raises costs for service industries. The legacy mining sector has struggled with lower prices and environmental rules, while newer renewable projects need engineers and managers who are often in short supply. These conditions help explain why Qinghai’s growth and incomes trail richer inland neighbors even with its resource base.

Are gaps starting to close

The inland coast gap is still wide, but some inland regions are catching up. Per capita GDP in 2024 topped 228,000 yuan in Beijing and 217,000 yuan in Shanghai, more than double the figures in many western provinces. Gansu, for instance, stood around 53,000 yuan. Yet central and western hubs are climbing. Hubei passed 100,000 yuan, and Chongqing reached roughly 101,000 yuan, reflecting gains in manufacturing and services. Differences remain stark between urban and rural districts, where disposable income can be one third to half of city levels in the same province.

In the northeast and some smaller western cities, population loss and weak private investment still weigh on growth. High speed rail brought visibility and access, but new stations alone do not guarantee thriving neighborhoods or factories. Projects such as new industrial towns have struggled in places that lack strong anchors, suppliers, or a clear business case. The lesson is that transport, land, and buildings must be matched with industries that can pay their way.

Human capital and foreign investment matter more than ever

Education has become the key driver of inland gains since the global financial crisis. Research comparing the pre crisis decade with the years after finds that advanced education contributes more to growth in inland provinces than before. As these regions shift from heavy industry toward electronics, autos, and services, returns to senior secondary and higher education rise. Scholarships, lower college entrance thresholds for less developed provinces, and transfers of teachers and curricula all help build the base.

Foreign direct investment plays a complex role. At the national level, foreign capital supports growth by supplying technology, competition, and access to networks. At the regional level, the effect is uneven. Some inland cities gain when policy focuses on sectors they can realistically scale and when local rules protect fair competition. Others see little change if subsidies chase industries without suppliers, customers, or workers. Tailored investment policies that reflect local strengths tend to work better than uniform incentives that spread funds too thin.

How researchers track change from space and in city accounts

Traditional statistics capture only part of the story. Satellite images of nighttime lights offer another lens on development because brighter lights tend to track urban activity. These data reveal deeper disparities at county level than city level and show a persistent brightness gap between the east and much of the west. The method helps planners see where growth clusters are forming, even before full economic data are available.

Another lens is the link between carbon emissions and value added across city trade networks. Studies find that developed cities often capture more value from production while some less developed areas bear a larger share of emissions. Carbon and value added can shift along supply chains from inland energy and materials producers to coastal assembly and service centers. That pattern calls for region specific climate policies so that cities that host energy intensive activities are not left with a heavier burden without the means to upgrade.

Why Wuhan and Chongqing moved faster than others

Both cities drew on strong anchors. Wuhan had universities and a legacy of optics research, which lowered the barrier to building Optics Valley and moving early on intelligent vehicles. Chongqing leveraged its scale in autos and electronics, its port on the upper Yangtze, and later the land bridge to Europe. These anchors reduce risk for suppliers and logistics firms, which in turn make the region more attractive for new plants and service providers. Once a cluster gains critical mass, firms can find workers, test products, and deliver on time with fewer bottlenecks.

Policy consistency also mattered. Clear land rules in industrial parks, faster permits for new lines, and service windows for small businesses can make the difference between a delayed plant and one that opens on schedule. Inland governments that focused on skills, supplier depth, and power reliability tended to win more advanced projects than places that relied on cheap land alone.

The hard part ahead

Three constraints could slow inland convergence. First, domestic demand is weak by historical standards, which makes it harder for new plants to reach scale if exports soften. Second, many inland provinces face aging populations and outmigration from smaller cities and rural areas. That shrinks the local customer base and reduces the pool of new workers. Third, global technology restrictions can limit access to advanced tools that local firms need to move up in value chains.

There are ways to respond. Improving local service sectors, including health care and elder care, can create jobs that are less exposed to global cycles. Strengthening vocational training linked to employers can raise productivity in factories that already operate inland. Better targeting of subsidies can avoid white elephant projects and direct funds to suppliers that reduce import dependence in areas like sensors, power electronics, and software.

Equity, cohesion, and national objectives

Regional policy is tied to social goals as well as growth. Western border regions such as Xinjiang show uneven development within the province, with wealth concentrations around transport hubs in the north and persistent gaps in the south. Studies link progress there to better accessibility, urbanization, and targeted support for local enterprises. Transportation upgrades and fair access to public services remain central to improving outcomes in counties that have long lagged behind their northern neighbors.

Bringing inland regions closer to the national average also supports broader goals. A larger middle class outside the coast can support domestic consumption and reduce pressure on migration to the largest coastal cities. Cleaner power from the northwest can lower emissions where demand is highest. The test for policy is whether investment and regulation can balance innovation with fairness so that inland cities grow into self sustaining centers rather than reliance on transfers.

At a Glance

- Wuhan, Chongqing, and Xining anchor a new inland growth push with advanced manufacturing, logistics, and green energy

- Policies from Go West to dushiquan have shifted investment toward central and western provinces and built city clusters

- Wuhan leads in intelligent connected vehicles and optics through local rules and a strong research base

- Chongqing couples the upper Yangtze location with a vast rail hub and a deep manufacturing ecosystem

- Qinghai holds rich solar, wind, and lithium resources but faces talent shortages and distance related costs

- Per capita GDP remains far higher along the coast, yet Hubei and Chongqing now exceed 100,000 yuan per person

- Education and tailored foreign investment policies drive inland gains more than uniform subsidies

- Nighttime lights and carbon value studies show inland coast inequalities in brightness and emission burdens

- Weak demand, demographics, and technology access are the main risks to sustained inland catch up

- Balanced growth requires skills, supplier depth, reliable power, and smarter project selection