Introduction: The Vanishing Childhood in South Korea

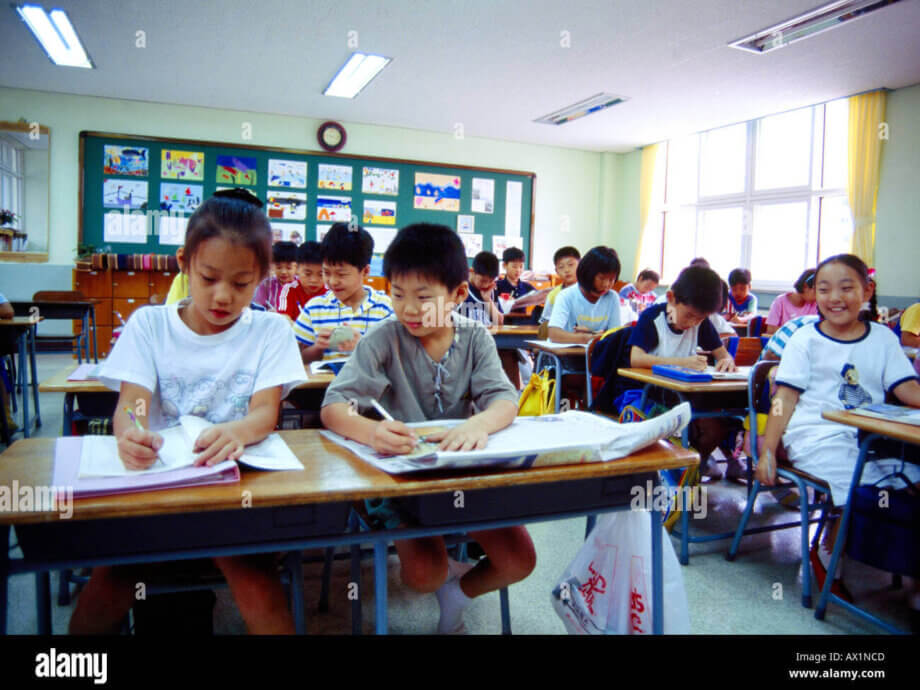

In South Korea, childhood is increasingly defined not by play and exploration, but by relentless academic pursuit. The nation’s remarkable rise from poverty to global economic powerhouse is often credited to its education system, which consistently produces top scores in international assessments. Yet, beneath these achievements lies a troubling reality: South Korean children are among the unhappiest in the developed world, with playtime and mental well-being sacrificed at the altar of academic success.

- Introduction: The Vanishing Childhood in South Korea

- How Academic Pressure Shapes Daily Life

- The Roots of the Pressure: Culture, Policy, and Parental Anxiety

- The Decline of Play: Quantity and Quality

- The Mental Health Crisis: Unhappiest Children in the OECD

- Teachers Under Siege: The Collateral Damage of Parental Pressure

- Societal Consequences: Inequality, Family Strain, and Demographic Challenges

- Efforts at Reform: Can the System Change?

- Global Context: A Widespread Decline in Play

- In Summary

How Academic Pressure Shapes Daily Life

For many South Korean children, the day begins and ends with study. Take the case of Kim Min-jae, 11, whose schedule includes English study every morning, after-school piano and taekwondo academies, and hours of homework before bed. Even weekends offer little respite. When Kim skipped an English session, he was barred from joining friends in an online game—a small but telling example of how play is often conditional, a reward for meeting academic expectations rather than a right of childhood.

This is not an isolated case. According to a survey by the Korean Teachers & Educational Workers’ Union, 62 percent of fourth to sixth graders have less than two hours of free time daily, and nearly 16 percent have less than one hour. The majority of this limited free time is often spent on screens or solitary activities, not on unstructured, social play.

Hagwons: The Engine of Academic Competition

Central to this culture are hagwons—private after-school academies that specialize in everything from math and English to music and sports. Nearly half of children under six attend these institutions, and by middle school, attendance is nearly universal. The average South Korean family spends a significant portion of its income on private education, with wealthier families investing even more, deepening educational inequality.

Hagwons are not just a supplement to public education; they are a parallel system that extends the school day late into the evening. For some students, this means up to 12 hours of study per day, leaving little time for rest, let alone play.

The Roots of the Pressure: Culture, Policy, and Parental Anxiety

South Korea’s “education fever” is rooted in a complex mix of historical, cultural, and economic factors. The legacy of Confucian values places a premium on academic achievement as a path to social mobility and family honor. The country’s rapid economic development in the late 20th century reinforced the idea that education is the key to personal and national success.

But this drive has created a system where the stakes are extraordinarily high. The national college entrance exam, known as the Suneung, is a once-a-year, high-pressure test that can determine a student’s entire future. On exam day, the country comes to a near standstill to support test-takers, underscoring the exam’s significance.

Parental Expectations and the Burden of Private Education

Parents, anxious about their children’s prospects, often push them into a relentless cycle of study and extracurricular activities. This pressure is not limited to academics; it extends to teachers, who face intense scrutiny and even harassment from parents dissatisfied with their children’s progress. The financial burden is also significant, with some families spending up to 20 percent of their income on private education. Research shows that this economic strain can lead to depression, particularly among fathers who feel responsible for funding their children’s educational ambitions.

Former teacher and education expert Insoo Oh, from Ewha Womans University, explains:

“Even at the elementary level, students feel pressure to study well due to parental expectations, which are so high. This pressure only increases as they approach middle and high school.”

The Decline of Play: Quantity and Quality

Playtime for South Korean children has declined sharply, both in quantity and quality. Studies show that children spend most of their limited free time on screens—smartphones, computers, and television—rather than engaging in active, social play. According to the Welfare Ministry, over a third of elementary students are at risk of excessive smartphone use.

Even during school breaks, most children remain indoors, often working on assignments or attending online classes. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this trend, as playgrounds were closed and, even after reopening, parental concerns about safety and academic progress kept children inside.

Why Play Matters: The Science of Childhood Development

Experts warn that the lack of play has serious consequences for children’s emotional, social, and cognitive development. Play is not just a leisure activity; it is essential for learning how to negotiate, empathize, and solve problems. Through play, children develop resilience, creativity, and the ability to cope with setbacks.

Kim Jae-won, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at Seoul National University Hospital, emphasizes:

“Play is inevitable for children’s emotional and social development. When they lack play, it causes problems in social skills development. Through play, children learn how to adjust their opinions, show consideration, read and empathize with others, and emotionally communicate with others. They sometimes feel discouraged, but learn how to endure it. When they lack this emotional adjustment or capacity to endure discouragement, it could lead to depression or anxiety disorders.”

The Mental Health Crisis: Unhappiest Children in the OECD

South Korea’s academic success comes at a steep cost. International surveys consistently rank Korean children at the bottom in terms of happiness and life satisfaction among OECD countries. The nation also has the highest youth suicide rate in the developed world, with suicide remaining the leading cause of death among young people for over a decade.

Academic pressure is a major source of stress. A 2024 report by the National Assembly Research Service found that the percentage of elementary students getting sufficient sleep has dropped, while suicide attempts among middle schoolers have surged. The Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey links academic achievement stress to increased risk of suicidal ideation and attempts, especially among adolescents experiencing stress at home or school.

Academic Helplessness and the Role of Physical Activity

Research shows that academic helplessness—feeling unable to meet expectations despite effort—can lead to depression and lower life satisfaction. However, participation in physical activity can mitigate these effects. Adolescents who engage in regular leisure-time physical activity report higher self-esteem and better body image, even under significant academic pressure. Yet, opportunities for such activities are dwindling as academic demands crowd out time for sports and recreation.

Teachers Under Siege: The Collateral Damage of Parental Pressure

The culture of academic competition affects not only students but also teachers. In recent years, South Korea has seen a disturbing rise in teacher suicides, often linked to harassment and unrealistic demands from parents. Teachers report being inundated with complaints, sometimes facing police investigations over minor incidents. The erosion of trust between parents and teachers has created a toxic environment, making it difficult for educators to support students’ holistic development.

Primary school teacher Kim Min Jun recounts:

“I try to do my job and role diligently. But now, to avoid doing anything that could potentially be reported as child abuse, I don’t really discipline the students anymore.”

In response to public outcry, the government has introduced measures to protect teachers, including legal support and penalties for parents who interfere with educational activities. However, experts argue that deeper cultural change is needed to restore respect for teachers and prioritize children’s well-being over test scores.

Societal Consequences: Inequality, Family Strain, and Demographic Challenges

The obsession with academic achievement has far-reaching consequences for South Korean society. Educational inequality is widening, as wealthier families can afford more private education, giving their children a competitive edge. This, in turn, fuels a cycle of competition and anxiety among parents and students alike.

The financial and emotional strain of supporting children’s education is also linked to declining birth rates, as families limit the number of children they have to manage costs. Parental depression, particularly among fathers, is rising as the economic burden grows. These pressures threaten the fabric of family life and the nation’s long-term social stability.

Efforts at Reform: Can the System Change?

Recognizing the crisis, South Korean policymakers have begun to experiment with reforms aimed at reducing academic pressure. One notable initiative is the “exam-free semester” in middle schools, which eliminates midterms and finals for one semester and replaces some academic instruction with career exploration and creative activities. Early results are promising: students report improved relationships with teachers, greater enjoyment of learning, and reduced stress.

Other reforms include capping hagwon hours, promoting vocational education, and revising college admissions policies to value extracurricular activities and personal growth alongside test scores. However, these efforts face resistance from parents and a deeply entrenched culture that equates academic achievement with future success.

The Hechinger Report notes:

“Although the initiative can be considered ‘small’ in the sense that it focuses primarily on one grade level, in only a few years it has grown to reach all 450,000 seventh graders in South Korea. There is now at least a hope that support for a more humanistic education might find a foothold, and, eventually, begin to spread.”

Global Context: A Widespread Decline in Play

South Korea is not alone in facing a decline in children’s playtime. Globally, children’s outdoor play has dropped by 50 percent in recent generations, driven by longer school hours, increased academic demands, the rise of screen time, and the disappearance of safe play spaces. However, the intensity and early onset of academic pressure in South Korea make its situation particularly acute.

Experts worldwide agree that balancing academic achievement with play, creativity, and emotional well-being is essential for raising healthy, resilient children. As countries strive for excellence, the South Korean experience serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of prioritizing test scores over happiness and holistic development.

In Summary

- South Korean children face intense academic pressure from an early age, with daily schedules dominated by school, private academies, and homework.

- Playtime has declined sharply, both in quantity and quality, with most free time spent on screens rather than active, social play.

- The culture of academic competition is driven by historical, cultural, and economic factors, reinforced by high-stakes exams and parental expectations.

- This pressure has led to high rates of stress, depression, and suicide among children and adolescents, as well as rising parental depression and family strain.

- Teachers are also affected, facing harassment and unrealistic demands from parents, contributing to a rise in teacher suicides.

- Efforts at reform, such as the exam-free semester and limits on hagwon hours, show promise but face cultural resistance.

- The South Korean experience highlights the need for a balanced approach to education that values play, creativity, and well-being alongside academic achievement.