High stakes decision for palm oil and energy

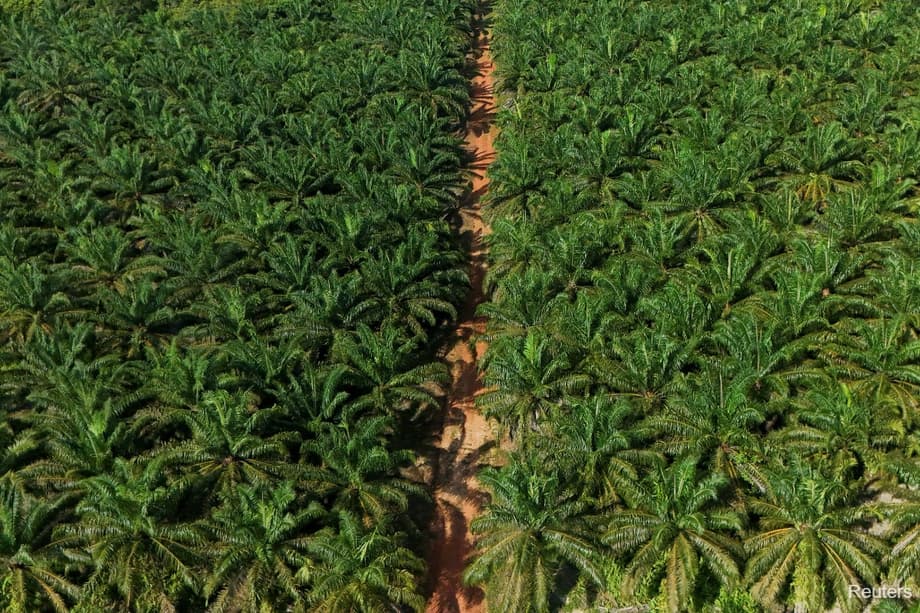

Indonesia plans to open 600,000 hectares of new land for palm oil over the next four years, a sharp policy turn after a freeze on new permits that lapsed in 2021. Officials say the goal is to lift stagnant production and secure supplies for food and transport fuels as the country raises its biodiesel mandate. Of the new area, 400,000 hectares are earmarked for smallholders through partnership schemes known locally as plasma, while an initial 200,000 hectares will be offered to state firm PalmCo, with private companies invited to join. The government insists forests will not be cleared, though it has not specified what non-forest land will be used. Environmental groups and academics are unconvinced, warning that available non-forest land is limited and that expansion risks fresh conflicts, higher emissions, and setbacks to climate commitments.

- High stakes decision for palm oil and energy

- What the plan includes and who benefits

- Can new estates avoid forest loss

- Biofuel policy is driving demand

- Yields, replanting and the productivity gap

- Economic stakes and smallholders

- How much deforestation is linked to palm oil

- Paths to meet demand without new clearing

- Policy choices in the months ahead

- What to Know

The Agriculture Ministry expects the plan to add roughly two million tons of palm oil output when fully planted. Indonesia already has about 16 million hectares under palm, but average yields have slipped to around 3.8 tons per hectare from above four tons in 2020. A United States Department of Agriculture foreign service forecast sees total Indonesian palm oil output at about 47 million tons in the 2025 to 2026 season, helped by better weather and more fertilizer use. The country is also moving from a B40 biodiesel blend to a possible B50 next year, a shift that could absorb more crude palm oil domestically and leave fewer volumes for export.

What the plan includes and who benefits

At the core of the expansion is a larger role for plasma plantations, where smallholders cultivate oil palm in partnership with a company that provides seedlings, agronomy support, and access to mills. These schemes are meant to spread gains to rural communities while improving oversight and traceability. The new plan allocates two thirds of the area to these smallholder arrangements, a sign that the government wants to tie output growth to livelihoods as well as to energy security.

State owned PalmCo is slated to receive an initial 200,000 hectares, and additional tracts will be opened to private operators. Officials have pledged to avoid clearing forests and peatlands, but have not yet detailed the type or location of the non-forest land that will be used. The balance between rapid development and careful screening will shape whether the program raises incomes and output without sparking fresh environmental damage or land disputes.

Can new estates avoid forest loss

The government’s assurance that forests will not be cleared is central to the credibility of the expansion. Greenpeace and other groups argue that unallocated, conflict free land that is suitable for oil palm is scarce. They warn that opening new estates without precise mapping could push cultivation into sensitive ecosystems or areas claimed by communities, triggering disputes and undermining emission reduction pledges.

Political rhetoric has added heat to the debate. At a public event in early January, President Prabowo Subianto sought to defuse concerns by likening oil palm to forest trees.

“Oil palms are trees, they have leaves.”

Scientists responded that a plantation is not a forest. Professor Budi Setiadi Daryono, Dean of the Faculty of Biology at Gadjah Mada University, cautioned that plantation monocultures strip out habitat complexity and fail to support wildlife.

“Palm oil plantations cannot serve as wildlife habitats and have almost no biodiversity.”

Peatlands and high carbon stock areas

Clearing peatlands or high carbon stock forests would turn the expansion into a source of significant emissions. Peat soils hold large carbon stores, and drainage to plant oil palm can lead to fires and long lasting haze episodes. Avoiding peat and primary forests, along with strict protection of riparian buffers and steep slopes, is essential if new plantings are to align with climate goals and corporate no deforestation commitments that govern access to premium markets.

Biofuel policy is driving demand

Indonesia launched a nationwide B40 mandate in early 2025, which requires diesel at the pump to contain 40 percent palm based biodiesel. Policymakers aim to raise this to B50 as soon as next year. The current blend already absorbs a large share of domestic palm oil, and a shift to B50 would push demand higher. Analysts estimate that biodiesel consumption could reach about 14 to 15 million tons under B40, rising toward 18 million tons if B50 is achieved. The USDA foreign service projects total domestic use, including food and industry, at around 22.6 million tons in 2025 to 2026.

There is caution inside government on the pace of the next step. Eniya Listiani Dewi, Director General of New, Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation at the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry, said the plan is still under review.

“The government has not yet made a final decision on implementing the B50 policy in 2026, and we are still calculating the volume of FAME required.”

Officials say biodiesel can cut the oil import bill and reduce emissions from transport. Economists point to fiscal and supply risks. Raising the blend rate requires sustained subsidies, expansion of biodiesel production capacity, and steady palm oil supply in a market influenced by weather, fertilizer costs, and global prices. Export levies and domestic market rules can cushion some of these pressures, yet they also shift costs, sometimes to consumers or the state budget.

Yields, replanting and the productivity gap

Indonesia’s headline production has plateaued in recent years as mature trees age and productivity dips. Average yields have fallen to roughly 3.8 tons of oil per hectare, and smallholders typically produce far less per hectare than corporate estates. Many smallholder plots have trees older than 25 years, which reduces output and heightens pests and disease risks. The government has promoted a subsidized replanting scheme to help farmers swap out aging stands for higher yielding varieties, but uptake has been slower than expected.

According to official figures, about 400,000 hectares have been approved for replanting out of a 2.5 million hectare target. Farmers cite hurdles such as land titles, paperwork, and the loss of income during the three to four year period before new trees bear fruit. These constraints are solvable but require coordination, patient finance, and a stronger network of extension services to provide technical advice.

Why replanting lags

Bridging finance that covers living costs during the replanting years, larger grant amounts for certified high yield seedlings, and simpler verification for land documents would remove major bottlenecks. Better access to fertilizer and agronomic support can lift yields rapidly without any new clearing. Some studies suggest national yields could move toward six tons per hectare with improved seeds and management. The USDA foreign service expects a near term output increase as fertilizer costs ease and weather normalizes, but sustained gains will depend on how quickly replanting accelerates across millions of smallholder hectares.

Economic stakes and smallholders

The palm oil sector remains a bedrock of Indonesia’s rural economy and export earnings. The Agriculture Ministry’s plantation directorate says palm oil accounted for more than half of agricultural export value in 2024 and generated about 4.2 million direct jobs, with another 12 million in related activities. Speaking at the Indonesian Palm Oil Conference, the Director General of Plantation, Abdul Roni Angkat, underlined the sector’s importance for livelihoods and foreign exchange.

“More than half of Indonesia’s agricultural export value is dominated by palm oil.”

Stronger governance is also part of the economic picture. Authorities have flagged irregularities across parts of the sector, including millions of hectares of plantations that lack proper permits, which auditors say has cost the state significant revenue. Bringing these areas into compliance through clear mapping, law enforcement, and transparent tax and royalty collection is essential for credibility at home and in export markets.

How much deforestation is linked to palm oil

There is active debate about palm oil’s share of Indonesia’s deforestation. Industry aligned analyses argue that palm oil accounts for a minority of total forest loss over the long arc, and that a large share of plantations were established on degraded land left by earlier logging waves. They also stress that deforestation rates peaked years ago and that recent years have seen improvements in monitoring and corporate policies.

Conservation researchers counter that oil palm has been a major driver of old growth forest loss in Indonesia over the past two decades, especially in Sumatra and Kalimantan. Clearing peatlands magnifies emissions and fire risk, while conversion of natural forests fragments habitats and pushes endangered species toward the brink. Both views underscore that location is everything. New estates on degraded mineral soils carry far lower climate costs than plantings that replace primary forests or peat.

Paths to meet demand without new clearing

Analysts who favor a productivity first strategy say Indonesia can meet domestic energy targets and sustain exports by lifting yields and diversifying biofuel feedstocks. One scenario modeled by Indonesian civil society groups warns that a business as usual push to reach higher biodiesel blends could require millions of additional hectares of palm, imposing billions in ecological and social costs. An alternative scenario prioritizes replanting aging farms, improving seed quality, and channeling investment into community scale biofuels from sources such as used cooking oil and non palm oil crops. This approach avoids deforestation, spreads income locally, and still meets fuel mandates if yields rise and collection systems for alternative feedstocks are scaled.

The same analysis argues that Indonesia is already close to an environmental carrying capacity for oil palm area. It urges capping further expansion near current levels and focusing on intensification, land rehabilitation, and better governance. That message aligns with what many global buyers require. Companies seek proof that supplies are traceable and free of deforestation, with special scrutiny on peatlands and primary forests.

Policy choices in the months ahead

Several decisions will determine whether the expansion meets energy and welfare goals without undermining climate and market access objectives. First, authorities need to publish a credible land bank that identifies non-forest, non-peat, low conflict areas suitable for oil palm, paired with geospatial transparency so communities and watchdogs can verify claims. Second, the smallholder replanting program should be scaled with better finance, crop insurance, and income support during the non-productive years so families can replant without falling into debt.

Third, enforcement against illegal clearing must be coupled with pathways to compliance for growers who meet environmental criteria. Fourth, energy planners should keep a flexible biodiesel mandate that reflects feedstock availability, fiscal space, and food price stability. Finally, trade policy should anticipate stricter import rules in destination markets, especially Europe’s deforestation regulation, by boosting traceability and certification across the supply chain. Industry trackers say a growing share of global palm supply now meets deforestation free standards, helped by satellite monitoring, block chain traceability, and stronger corporate policies. Indonesia’s producers, including smallholders, will benefit from programs that bring them into these verified supply chains.

What to Know

- Indonesia will open 600,000 hectares of new palm oil plantations over four years, with 400,000 hectares for smallholder plasma schemes and 200,000 hectares initially to PalmCo.

- Officials say forests will not be cleared, but the government has not specified the type or location of non-forest land to be used.

- The expansion could add about two million tons of output, while national yields have fallen to around 3.8 tons per hectare.

- B40 biodiesel is in place and B50 is under consideration, which would raise domestic palm oil use and could reduce exports.

- A USDA foreign service forecast puts Indonesia’s palm oil production around 47 million tons in 2025 to 2026, supported by better weather and more fertilizer use.

- Environmental scientists warn that plantations are not forests, and stress that avoiding peatlands and high carbon stock areas is critical.

- Replanting lags the national target, with about 400,000 hectares approved against a 2.5 million hectare goal, reflecting finance and paperwork hurdles.

- The sector is a major employer and export earner, yet compliance gaps and illegal plantings pose risks to state revenue and market access.

- Analysts say Indonesia can meet fuel and food demand by lifting yields and scaling community based biofuels, reducing the need for new land.

- Trade partners are tightening deforestation rules, making traceability and verified deforestation free supply a competitive necessity for Indonesian producers.