Inside the rankings puzzle

Global lists of liveable cities often feature familiar names such as Vienna, Copenhagen, Melbourne and Zurich. Mainland Chinese cities rarely appear near the top of those global leaderboards, even as China has transformed its urban life at a speed and scale with few parallels. The gap between global rankings and life on the ground is striking to anyone who has watched Beijing expand its metro network, strolled Shanghai’s restored waterfront neighborhoods, or seen Wuhan’s green corridors soak up summer downpours.

- Inside the rankings puzzle

- What do the big indexes measure, and where do Chinese cities fall?

- Regional and perception based rankings tell a different story

- What liveability looks like at street and community level

- Smart city policy and digital upgrades

- Services, safety, and culture residents cite

- Why many Western indexes still penalize Chinese cities

- City snapshots: Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and Suzhou

- How definitions shape outcomes

- Key Points

What counts as liveable depends on who is measuring, and for whom. Some indexes grade how comfortable life is for expatriate managers posted abroad. Others take a broader view and include culture, education, and public health. Many residents and frequent visitors describe Chinese cities as safe, convenient and culturally rich, with abundant public spaces, community exercise and dance, and easy digital services for deliveries and transport. That lived experience does not always align with the international lists that get headlines.

This article examines why. It looks at how leading indexes score cities, what regional and research based assessments say about Chinese urban life, where Chinese cities excel, and where they still trail. It also highlights case studies that show how policies on parks, transit, smart services and heritage can raise quality of life.

What do the big indexes measure, and where do Chinese cities fall?

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Liveability Index grades cities on stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure. Mercer focuses on quality of living for international staff, including housing, healthcare access, international schools, recreation, and ease of doing daily tasks. Monocle’s survey adds a lifestyle angle, spotlighting things like urban design, cafes, street life and leisure.

Chinese cities do appear in these indexes, usually outside the top tier. In some years Suzhou has ranked as the most liveable city on the Chinese mainland in the EIU list, ahead of Beijing and Shanghai, which often score well for education, transport links and culture but lose points for air quality and other environmental measures. Hong Kong, measured separately from the mainland, tends to place higher within Asia in international comparisons.

Editors at the EIU have long argued that their method weighs many items. Jon Copestake, editor of the EIU survey, explained that pollution is only one part of a larger scorecard.

Pollution was just one of more than 40 indicator scores that form the overall weighted score for cities.

Tom Rafferty, an EIU economist based in Beijing, has also pointed to the city’s strengths in education, culture, consumer choice and connectivity.

It also has, I would argue, more cultural options than most other Chinese cities, a wider range of consumer goods and services, better international transport links, all factors that go into the liveability rating.

These comments help explain why megacities like Beijing and Shanghai, even with environmental challenges, can score in the mid bands on liveability while not breaking into top ranks that reward cleaner air and smaller scale urban stress.

Regional and perception based rankings tell a different story

Region specific lists and perception studies often lift Chinese cities higher. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme released an Asia Top 50 list for 2024 to 2025 that rates climate comfort, education and healthcare, relative economic prosperity, and the ratio of living costs to income. That ranking placed Guangzhou ninth in Asia and the highest on the Chinese mainland. The same list featured a long roster of Chinese cities, from Wuhan and Nanjing to Chengdu and Xiamen.

Selected placements in that UN associated assessment included:

- Guangzhou, ninth in Asia and first among Chinese mainland cities

- Wuhan, tenth

- Nanjing, fourteenth

- Suzhou, twenty sixth

- Qingdao, eighteenth

- Shanghai, fortieth

- Beijing, forty second

- Chengdu, forty ninth

Brand perception also matters. A global city brand index placed Hong Kong within the top fifty worldwide, with Shanghai and Beijing not far behind. Interestingly, Chongqing scored strongly on attributes such as liveability, governance and education even if it had lower familiarity among foreign respondents. Another Asia Pacific study of liveability, lovability and prosperity reported that China had the largest number of cities in the top hundred across the region. Beijing and Shanghai placed in the top ten for that regional report, reflecting strong scores in economic scale, culture and education, and regional reputation.

The message from these regional and perception based rankings is clear. Chinese cities perform better when judged within Asia, or when perception data from regional respondents is included, rather than in global lineups dominated by European and Anglophone standards and preferences.

What liveability looks like at street and community level

City wide averages can hide local realities. A nationwide study mapped 101,630 communities across 42 major Chinese cities using satellite imagery, points of interest, and building data. The research produced a granular community liveability index built from five headline categories and dozens of indicators. Living comfort emerged as the top priority in expert surveys behind the index, while building massing mattered least. Security construction lagged in less developed cities, and negative land uses such as nearby factories weighed heavily on local scores. The most common pattern was dense buildings and sparse green space, with sharp differences inside each city as well as across regions.

Street design also makes a difference. Research in Shanghai identified six qualities that define liveable streets in that city’s context:

- Social interaction

- Sense of belonging

- Local economic activities

- Local humanized environment

- Facilities and mixed uses

- Safety

Shanghai’s focus on sociability and local commerce stands out. Policies that open formerly gated compounds to the street grid, plus attention to pedestrian comfort and small business fronts, help sustain daily life beyond the metro and office tower scale.

Examples from several cities show how infrastructure choices translate into daily comfort. Wuhan’s sponge city program uses lakes, bioswales and permeable surfaces to absorb rain and temper heat. The Yangzi River Beach Park stretches more than seven kilometers, with a green buffer of trees and water gardens that doubles as flood protection and a leisure belt. Tianjin’s eco city runs a pneumatic waste collection network that moves refuse through underground pipes to centralized nodes, cutting odors, truck noise and spill risk while enabling round the clock service. Suzhou combines careful heritage preservation in its classical gardens with barrier free access and quiet modern amenities, blending aesthetics and function.

These projects, often delivered at district or corridor scale, reframe liveability as an experience of streets, parks and services that residents use every day. They also underline how much variation exists within any one city.

Smart city policy and digital upgrades

Smart city pilots across China have tested sensors, data platforms and digital public services for nearly two decades. A large panel study treating those pilots as a quasi natural experiment found that smart city policy raised urban liveability scores across economic, environmental, social security and daily convenience dimensions. The effect was stronger in large, knowledge rich cities that could apply technology and improve social governance. The research also found spillovers, with nearby non pilot cities seeing gains as practices and networks spread.

For residents, those programs show up as quicker access to clinics, more reliable buses, traffic management that reduces delays, digital utility payments, and city apps that bundle services. For visitors and expatriates, bilingual interface design and customer service matter just as much as the technology. Cities that translate smart tools into simple, accessible everyday use gain the most.

Services, safety, and culture residents cite

National surveys of residents suggest a mixed but improving picture. A study of 40 major Chinese cities reported moderate satisfaction with liveability. Respondents favored the convenience of public facilities, the natural environment, and the sociocultural environment. Dissatisfaction centered on urban security, environmental health and convenient transportation, though mobility has improved markedly in the years since the survey thanks to rapid metro expansion and a shift to electric buses and taxis in many cities.

Street safety is often cited by residents and frequent travelers as a strength. Walking at night in central Beijing or Shanghai feels routine for many, and police presence is visible. Universities such as Peking University and Tsinghua, and cultural institutions from the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing to venues in Shanghai’s West Bund, contribute to a rich calendar of concerts, exhibitions and festivals. Public healthcare coverage is broad, large hospitals are modern, and clinics of traditional Chinese medicine provide complementary care that many residents value.

Digital commerce and logistics also shape daily life. Groceries and meals arrive in minutes through couriers, platforms locate nearby services, and QR code payments are almost universal. Newcomers sometimes face a learning curve with local apps and cashless systems, yet bilingual help is improving in central districts frequented by tourists and foreign workers.

Why many Western indexes still penalize Chinese cities

Environmental stress remains the most common drag on scores. Air quality has improved in many large cities compared with a decade ago, but seasonal haze still occurs and heavy industry upwind can offset local progress. Climate change brings heat waves to the south and cold snaps to the north, which strains power, health services and outdoor comfort. A nationwide analysis from 2006 to 2016 found a steady rise in liveability scores, yet also showed that extreme heat, heavy rain and freezing events reduce liveability in different regions.

Language and service access matter for expat focused indexes. Availability of international schools, English speaking medical staff, and familiar retail choices can shift a city’s score even if residents are largely satisfied with local options. Digital ecosystems can be a barrier for new arrivals who have not set up local payments or mobile numbers. Some rankings include perceptions of governance and media freedom within their stability or reputation pillars. That weighting tilts the field toward cities in countries that share the values or legal systems of the ranking organization’s home audience.

Property cycles, fast urban growth and the household registration system can also shape city scores. Migrant families sometimes face hurdles enrolling children in public schools, and older districts can lag on green space per person. At the same time, cities known for parks, water corridors and community programming, such as Chengdu’s investment in green walls and street level planting, gain day to day comfort that many indexes do not fully capture.

Methodology nuance from the EIU sheds light on why Beijing can outscore other mainland cities even during periods of high smog. The EIU’s editor has stressed that air pollution is one indicator among many.

Pollution was just one of more than 40 indicator scores that form the overall weighted score for cities.

Its Beijing based economist has pointed to the capital’s relative strengths in culture, consumer choice, education and transport access.

It also has, I would argue, more cultural options than most other Chinese cities, a wider range of consumer goods and services, better international transport links, all factors that go into the liveability rating.

These remarks, and the structure of the indexes, help explain the outcomes. They do not settle the debate about whether those criteria reflect what residents in different cultures value most, or whether alternate measures such as community comfort should count more.

City snapshots: Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and Suzhou

Beijing retains a distinctive urban form laid out on a north south axis with concentric ring roads. The skyline rises beyond former hutong neighborhoods, many of which now host cafes and small galleries. The metro system, among the busiest in the world, has grown to serve even distant suburbs. Night walking feels routine in central districts and around university campuses. Weekends bring crowds to the Western Hills, and new parks and restored river corridors add breathing room to a dense city. Tourist highlights sit alongside daily life amenities such as community fitness equipment and pocket parks.

Shanghai is the mainland’s most international city. Planners preserved its historic 1920s and 1930s architecture in the old concession areas and pushed new towers to Pudong across the Huangpu River. Many buses and taxis run on electricity, and the streets are quieter than they were a decade ago. Rail corridors double as green strips in some districts. Local studies find that social interaction and local commerce keep streets lively. For newcomers, the city’s retail and food scenes feel accessible, and bilingual signage is common on main arteries and transit hubs.

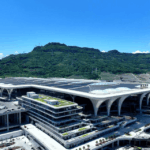

Wuhan carries lessons in urban resilience. Long known as a furnace for summer heat, it added shade trees and built wetlands and lakes into the city fabric to absorb rain and lower temperatures. The Yangzi River Beach Park offers continuous public access along the waterfront and functions as flood control. Public squares host dance and exercise in early mornings and evenings, which builds community ties as much as it improves health.

Suzhou shows how heritage and modern planning can reinforce each other. Classical gardens prioritize calm and artistry, with careful restoration, clear but unobtrusive signage and ramps that allow seniors and families with strollers to enjoy the sites. Suzhou Industrial Park, developed with Singapore, applies clear planning rules, mixed use districts and coordinated transport, and has become a model for human centered growth in a fast changing economy.

How definitions shape outcomes

Liveability is not a single idea. If the goal is to support expatriate staff, then access to international schools, language friendly services and familiar recreation will carry weight. If the goal is to judge daily life for residents, then community comfort, microclimate, social ties, and functional parks may matter more. The EIU, Mercer and Monocle approaches, while rigorous in their own ways, reflect a certain set of preferences. Regional and perception based lists can elevate different strengths, such as climate comfort and the balance between income and living costs.

Chinese cities excel in rapid transit, public safety in many districts, cultural venues and digital convenience. They lag where air quality and climate stress persist, where green space is still catching up in older neighborhoods, and where migrants face barriers to services. Smart city programs, sponge city retrofits, street design tuned to social life, and open data that invites comparison can raise scores and, more important, improve daily comfort for residents and visitors.

Key Points

- Mainland Chinese cities often rank below top ten on global liveability indexes used by companies and international media

- EIU, Mercer and Monocle weigh stability, healthcare, education, culture and infrastructure, with methods that favor environmental quality and expat friendly services

- UN associated Asia rankings place many Chinese cities in the regional top fifty, with Guangzhou ninth and Wuhan tenth

- Brand and perception studies show Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing scoring well on familiarity and significance, while Chongqing stands out for governance and liveability attributes

- Community scale research across 42 cities finds strong variation within cities, with living comfort ranking highest for residents and security construction lagging in less developed regions

- Street level studies in Shanghai emphasize social interaction, a sense of belonging and local commerce as core qualities of liveable streets

- Smart city policies have raised liveability, especially in large and knowledge rich cities, with positive spillovers to neighbors

- Air quality progress is uneven and climate extremes reduce liveability in different regions, which affects global scores

- Expats face service and language hurdles that weigh on some rankings, even as residents report improvements in transit and public facilities

- Case studies in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and Suzhou show how parks, waste systems, heritage and transit upgrades translate into daily comfort