Why 114th place matters now

In the 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), the Philippines ranked 114th out of 180 countries with a score of 33 on a scale where 0 means highly corrupt and 100 means very clean. The score fell by one point from 34 in 2023. The rank moved up by one place because of ties and shifts among peers, but the performance still sits well below the global average of 43 and the Asia Pacific average of 44, according to Transparency International. The CPI compiles expert and business assessments of public sector corruption and is one of the most watched barometers of governance.

- Why 114th place matters now

- How the CPI works and what it does and does not measure

- What the numbers say about the Philippines

- Flood control contracts put procurement under the microscope

- Asia Pacific picture and the climate risk link

- What could lift the score and strengthen integrity

- What this means for business and investment

- Key Points

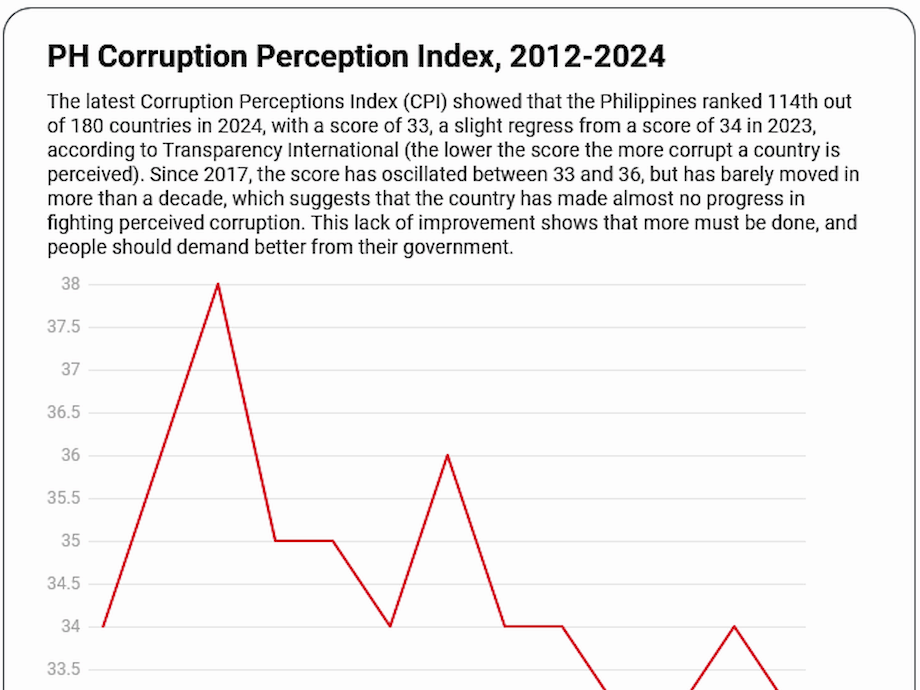

For more than a decade, the country’s CPI scores have barely budged. From 2012 to 2024, the Philippines hovered between 33 and 38, with the best year in 2014 at 38 and the weakest results at 33 in 2021, 2022 and now 2024. The narrow band suggests persistent problems in accountability, procurement, law enforcement and political finance. It also hints at the difficulty of translating policy pledges into results that are visible to investors and citizens. Policy institutes in Manila note that the current score keeps the country behind neighbors that have moved faster on transparency and judicial efficiency.

At the top of the table are Denmark, Finland, Singapore and New Zealand. The bottom group includes South Sudan, Somalia and Venezuela. In the region, the Philippines trails Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, Timor Leste, China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Nepal and Thailand. It shares the same score with Laos and Mongolia and sits above Cambodia, Myanmar and North Korea.

How the CPI works and what it does and does not measure

The CPI ranks 180 countries and territories by perceived levels of corruption in the public sector. Scores are drawn from at least three credible sources among 13 surveys and assessments that include the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. Results are rescaled to a 0 to 100 score and combined, with care taken to report uncertainty. The 2024 edition draws on data covering roughly May 2023 to April 2024. Full results and method are available on the CPI 2024 results page.

What the index measures

Public sector corruption includes bribery, diversion of public funds, use of office for private gain, conflicts of interest, nepotism, procurement rigging and impunity for officials who break rules. The index reflects how often experienced observers see these patterns and how severe they are in state institutions.

Blind spots and cautions

The CPI is based on perceptions rather than direct counts of corruption cases. It does not track private sector wrongdoing or money flows that may move through offshore financial centers. It cannot pinpoint which agencies are clean or dirty. This is why the index is best read together with experience based surveys. In the Philippines, Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer found that 86 percent of people view government corruption as a big problem and 19 percent of users of public services reported paying a bribe in the previous 12 months.

What the numbers say about the Philippines

The trajectory since 2012 shows short bursts of improvement and long periods of drift. A mid decade peak at 38 proved fleeting. Pandemic era years saw slippage back to 33, and the 2024 score aligns with that low point. The slight rise in rank in 2024 reflects movement elsewhere as much as change at home. The country still sits below the global average of 43 and the regional average of 44, a reminder that peers continue to press ahead with institutional reforms.

University of the Philippines associate professor and data scientist Rogelio Alicor Panao has tracked this pattern for years and has challenged both leaders and citizens to demand stronger integrity. He framed the issue bluntly.

“Have we done enough to demand better?”

Policy researchers and business groups point to a familiar list of weak links. Procurement remains vulnerable when planning is fragmented and award data is incomplete. Case backlogs and limited resources slow anti graft enforcement. Political finance rules invite conflicts of interest. Many agencies still rely on paper based processes that delay audits and cloud accountability. Studies suggest more transparency in budgeting and procurement, wider public participation, and faster digital tools could help move the dial.

Flood control contracts put procurement under the microscope

Concerns about public works intensified with the disclosure of irregular flood control projects, popularly called ghost projects. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr said that from July 2022 to May 2025, only 100 billion pesos from a 545 billion peso flood mitigation budget had been awarded, and that the awards went to just 15 of 2,409 accredited contractors. The concentration of awards raised red flags and prompted reviews of how projects were programmed, vetted and monitored.

Addressing the matter, the President stopped short of naming suspects but signaled unease with what the audit surfaced.

“a disturbing assessment”

In a separate case, a senior Department of Public Works and Highways official was suspended and later arrested after an alleged attempt to bribe a member of Congress to halt a probe into irregular projects, according to regional media reports. The official faces charges under the Revised Penal Code and the Anti Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. The episode underscores both the risks in large infrastructure budgets and the need for credible enforcement that deters bribe seekers on all sides.

Proponents of procurement reform argue for routine publication of pre bid studies, bid evaluations and contract variations in machine readable formats. They also advocate regular rotation of bid and awards committee staff, tighter conflict of interest checks on contractors and use of analytics to spot red flags such as repeated single bidder awards or unusual cost patterns. These are the kinds of safeguards that move countries upward in the CPI and, more importantly, deliver better roads, schools and flood defenses.

Asia Pacific picture and the climate risk link

The average CPI score in Asia Pacific fell to 44 in 2024. Regional advisers say governments have not delivered on anti corruption pledges, and that weak controls are already harming climate action. The index connects the dots between corruption and the climate crisis, noting that stolen or misused funds, opaque lobbying and conflicts of interest can derail energy transitions and disaster readiness.

In its 2024 overview, Transparency International captured the connection in plain terms.

“The corruption crisis is a huge obstacle to solving the climate crisis.”

Few places feel the stakes like the Philippines, a storm exposed archipelago that faces rising seas and stronger typhoons. Climate finance for flood control, relocation, coastal protection and clean energy must reach intended communities. When corruption bleeds those funds, disaster losses mount, and public trust erodes. Transparency International also points out that more than a thousand environmental defenders were killed in the past five years, nearly all in countries scoring below 50 on the CPI, including the Philippines. Protecting civic space and whistleblowers is a governance issue and a climate issue.

What could lift the score and strengthen integrity

Independent assessments and local policy centers converge on practical steps that are within reach. Many do not require new laws, only follow through, better disclosure and the courage to open decision making to scrutiny.

- Make budget planning, procurement and auditing more transparent. Invite citizen monitors at each stage, from project selection to contract closeout.

- Publish full contract data, including awards, amendments and completion reports, in open formats. Expand electronic procurement so bids and awards can be tracked in real time.

- Open bicameral conference committee meetings to the public to avoid last minute insertions and double funding, a step urged by policy analysts.

- Harden anti bribery enforcement. Resource the Ombudsman, auditors and prosecutors so cases move faster and penalties stick.

- Protect whistleblowers and journalists so corruption reports trigger investigations instead of retaliation.

- Streamline permits and reduce red tape so ordinary transactions no longer depend on grease payments.

- Upgrade conflict of interest rules for officials and contractors. Verify beneficial ownership of bidders to reveal hidden links.

- Modernize agency processes and data systems. Reduce manual steps that slow audits and hide responsibility.

Analysts add that a stronger CPI result would not be an end in itself. It would be a signal that state institutions are improving, which in turn helps attract investment in infrastructure, technology and climate projects. Business media in Manila caution that a one place rise in rank without a higher score is unlikely to change investor thinking by itself. Credible reforms and steady enforcement do.

What this means for business and investment

Companies weigh corruption risk when choosing where to expand. They look for clean procurement, predictable courts, efficient customs and fair licensing. When scores stagnate in the low thirties, due diligence costs rise, fewer firms compete for public projects, and loan terms can be tougher.

At the same time, improvement is achievable. Countries that opened data, secured independent control bodies and protected civic space have moved upward over time. The Philippines has competitive advantages in talent and geography. Matching those with visible integrity gains would widen the pool of investors and lower risk premia.

Key Points

- The Philippines ranks 114th of 180 in the 2024 CPI with a score of 33, down one point from 2023.

- The global average is 43 and the Asia Pacific average is 44.

- The country’s best score since 2012 was 38 in 2014, while 33 in 2021, 2022 and 2024 marks the low.

- Rank rose by one place, but the underlying score declined.

- The Philippines trails many regional peers and shares its score with Laos and Mongolia.

- Transparency International warns that corruption undermines climate action across the region.

- In the Philippines, 86 percent say government corruption is a big problem and 19 percent of recent public service users reported paying a bribe.

- Flood control contract concentration and a DPWH bribery case have sharpened scrutiny of public works.

- Experts urge open procurement, public budgeting, faster digital systems and stronger enforcement.

- Better governance would help attract investment, while a small rank change without higher scores is unlikely to sway investors.