A test for forest finance at COP30

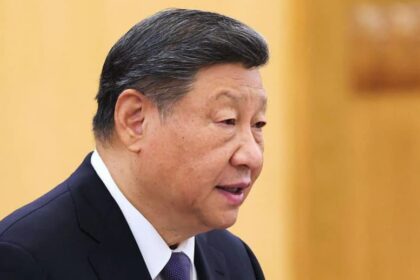

Brazil used the first week of the United Nations climate summit in Belem to launch the Tropical Forests Forever Facility, a fund meant to pay countries for keeping rainforests standing. The initiative opened with billions of dollars in early commitments and endorsements from dozens of governments. Expectations that China would arrive as a major early backer, however, did not come true. Chinese envoys conveyed support for the fund in principle, yet they argued that wealthy nations should take the first step on large scale climate financing. The position reflects a long running view in global climate talks that nations which industrialized earlier should carry more of the cost.

For Brazil, which is hosting the summit on the edge of the Amazon, a Chinese check would have sent a strong signal to other emerging economies and institutional investors that the fund is ready to scale. Instead, Beijing is withholding a financial pledge for now, citing common but differentiated responsibilities. That concept, embedded in the United Nations climate framework since 1992, says that developed countries bear the main obligations for financing and emissions cuts because their growth relied on fossil fuels. The debate over who pays, and when, has become sharper as countries struggle to mobilize finance at the speed required. Senior officials from the United States, China and India did not attend the opening sessions, a reminder of the political headwinds that color climate diplomacy.

Even without China, Brazil secured fresh momentum for the fund. Event organizers announced endorsements from 53 countries and pledges that together exceeded 5.5 billion dollars. Norway committed 3 billion dollars over ten years. Brazil and Indonesia reconfirmed commitments of 1 billion dollars each. Portugal offered 1 million dollars and the Netherlands 5 million dollars for the secretariat. France indicated a possible commitment of up to 500 million euros, and Germany formally endorsed the launch. A group of 34 tropical forest countries backed the declaration, representing well over 90 percent of tropical forests in the developing world.

How the Tropical Forests Forever Facility works

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility, or TFFF, is designed to turn forest conservation into a reliable source of national income. The plan targets a 125 billion dollar fund that combines 25 billion in sponsor capital from governments and philanthropies with 100 billion from private investors such as pension funds and asset managers. The capital would be invested through a dedicated vehicle that aims to earn returns in financial markets. Those returns would cover investor payments and provide annual transfers to countries that maintain or increase their tropical forest cover.

Unlike short grant cycles, the TFFF seeks permanent financing by operating as an endowment. To qualify for payments, countries must keep deforestation below an agreed baseline and meet transparency and governance standards. Payouts would be calculated using satellite monitoring of standing forest area and adjusted downward where loss or degradation occurs. At least 20 percent of the money is reserved for Indigenous peoples and local communities that serve as vital forest stewards. The World Bank will serve as trustee and interim host while Brazil and partners set up the Tropical Forest Investment Fund and a stand alone secretariat. The fund design also excludes investments with large environmental impacts and sets equal representation for sponsor and forest countries in governance bodies.

Why China is holding back

Chinese officials told Brazilian counterparts that the fund has merit, yet they maintain that developed economies should lead on climate finance. That stance aligns with Beijing’s interpretation of climate burden sharing. China has long described itself as a developing country under the climate regime. It has focused on cutting emissions at home and deploying technology abroad while resisting pressure to join multilateral climate funds as a donor. Joining as a financier would blur lines that Beijing has guarded for decades.

Another factor is how and where China prefers to spend climate money. Chinese agencies often channel resources through bilateral projects, state banks and initiatives like South South cooperation. Directing money into a new multilateral fund introduces questions about governance, crediting, and control over results. Brazilian officials have said that several governments, including China, want a say in shaping the TFFF’s final architecture before they write checks. That is a normal ask for a vehicle that aims to move public capital into private markets at global scale.

What the responsibility principle means in practice

“Common but differentiated responsibilities” is short for a principle set in the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. It recognizes that all countries share the duty to address global warming while reflecting differences in historical emissions and capacity to act. Under this approach, rich countries accept stronger commitments to finance mitigation and adaptation. Emerging economies take growing action at home, yet they have not been expected to bankroll climate funds. China has invoked this principle in nearly every round of climate negotiations. The TFFF sits outside the formal UN climate finance system, which could make it easier for large emerging economies to contribute later without setting a precedent that binds them in other arenas.

Brazil’s pitch and progress

Brazil is presenting the TFFF as its flagship contribution to a moment when forest protection can make or break global climate goals. The government points to a sharp reduction in Amazon deforestation compared with the peak years of the last decade and to a push to build a bioeconomy that values standing forests. At the same time, the country faces scrutiny for decisions that expand oil exploration and reopen old debates over highways through remote rainforest. The fund is meant to anchor a durable financial alternative to those pressures by making forest conservation pay.

In remarks in Belem, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva cast the mission in clear terms and urged a surge of public and private capital to match it.

Accelerating the energy transition and protecting nature are the two most effective ways to contain global warming. I am convinced that, despite our difficulties and contradictions, we need roadmaps to justly and strategically reverse deforestation, overcome dependence on fossil fuels and mobilise the necessary resources to achieve these goals.

Marina Silva, Brazil’s minister of the environment and climate change, described the launch in historic terms and said the goal is permanent protection rather than short cycles of aid.

The launch is a turning point for tropical forest conservation.

Ajay Banga, president of the World Bank, which will act as trustee and interim host of the facility, emphasized that the economics can align with the conservation mission when the fund reaches scale.

If scaled up, the benefits would result in good economics and good development.

Norway’s government framed its multiyear pledge as a response to the urgency of stopping deforestation and the need for predictable finance. European partners endorsed the model, and more than thirty heads of state and government delegates attended the launch. The structure allocates a fixed share of resources to Indigenous and local communities and places forest countries on equal footing with sponsor countries in decision making bodies, two features designed to build trust. Turning those features into financial contracts that investors accept will be the next test.

How much money is needed and why forests matter

Tropical forests hold vast stores of carbon and regulate rainfall across continents. Keeping them intact is one of the fastest ways to slow warming. Scientists warn that the Amazon risks reaching a tipping point where drier conditions lead to permanent changes in parts of the ecosystem. Beyond climate, forests support biodiversity, water security and livelihoods for millions of people. The TFFF tries to put a price on those services by paying countries for measurable results, country by country, so that treasuries and communities can plan ahead.

The financing gap remains wide. Researchers estimate that forest rich countries face tens of billions of dollars in unmet needs each year to halt deforestation and restore degraded land. Broader climate financing needs are measured in the trillions annually when energy, transport and adaptation are included. Governments and multilateral banks cannot fill that gap alone, which is why the TFFF leans on private investors alongside public sponsor capital. The promise is that a steady endowment can fund predictable payments to countries that keep forests standing while also paying back investors.

Supporters and critics weigh the design

Supporters see a chance to move beyond a patchwork of short grants and carbon projects by creating a global, rules based incentive that rewards verified results. Critics counter that investor returns might come first when markets are volatile, leaving forest countries with uncertain payments just when they need stability. Others worry that creating a financial asset out of nature can crowd out existing multilateral funds or weaken national programs that tackle illegal logging and land grabbing. The reliance on satellite data brings its own challenges, from measuring degradation to capturing activities that shift across borders. Advocates say these risks can be managed with strong safeguards, transparent rules and independent verification.

The architects of the TFFF included provisions to answer some of those concerns. At least one fifth of resources must flow to Indigenous peoples and local communities. The governance design grants equal seats to sponsor and forest countries. Investment portfolios exclude activities with large environmental harm. Payments are reduced where deforestation rises, which aims to keep incentives aligned over time. Whether those design choices will deliver predictable rewards at scale depends on how fast the endowment grows and how quickly pledges turn into signed contributions.

What could shift China’s calculus

China’s decision to hold back a pledge now does not foreclose future participation. Beijing may seek a formal role in governance before committing, or it may prefer to announce a contribution when the investment vehicle and risk sharing rules are fully defined. Cooperation platforms like the BRICS group and engagement with resource rich partners in the Middle East could also shape the timing. A Chinese contribution would give cover for other large emerging economies to join as financiers, not only recipients, which is one of Brazil’s strategic aims.

Chinese officials have in the past signaled interest in the concept while being cautious about amounts and timing. The country has built a record of large domestic investments in renewables and electric transport and prefers bilateral cooperation abroad. The TFFF is different. It seeks to redirect the logic of global capital toward forest outcomes. That kind of change often unfolds in stages. First endorsements, then design input, then early investments. The question now is how quickly sponsor capital accumulates to the first thresholds that unlock payments to forest countries.

What comes next for the fund

The immediate tasks are technical. Brazil and partners will finalize the secretariat, investment policies and verification rules. The World Bank will act as trustee while the Tropical Forest Investment Fund is stood up with sponsor and private capital. The fund has advertised a target of 25 billion dollars in sponsor commitments and 100 billion dollars from institutional investors for full operations. Governments involved in the design say they aim to complete a first round of investments by 2026. The secretariat plans to allocate resources across more than a billion hectares of tropical forests based on verified performance.

Success will depend on whether payments reach local actors and whether national policies align with the financial incentive to keep forests standing. That means secure land rights for Indigenous groups, enforcement against illegal deforestation, and credible national forest monitoring. It also means building systems that prevent leakage, where deforestation drops in one area but rises in another. Brazil is betting that a large, rules based endowment can give ministers of finance a reason to budget for conservation in the same way they budget for roads and hospitals. If payments are steady and transparent, treasuries and communities can plan, invest and build a durable forest economy.

Key Points

- China withheld a financial pledge to Brazil’s Tropical Forests Forever Facility, arguing that developed countries should lead climate finance.

- Brazil launched the fund at COP30 with endorsements from 53 countries and more than 5.5 billion dollars in early pledges.

- Norway pledged 3 billion dollars over ten years, Brazil and Indonesia each committed 1 billion dollars, with additional support signaled by European partners.

- The fund targets 125 billion dollars by pairing 25 billion in sponsor capital with 100 billion from private investors, operating as a permanent endowment.

- The World Bank will serve as trustee and interim host while a dedicated Tropical Forest Investment Fund and secretariat are established.

- At least 20 percent of payouts are earmarked for Indigenous peoples and local communities, and governance gives equal seats to sponsor and forest countries.

- Supporters see a predictable, rules based incentive for keeping forests standing, while critics warn of risks tied to market performance and fragmentation of climate finance.

- China could still join later, especially if it secures a role in design and governance as the fund moves from launch to implementation.